Resisting sentimentality, Laird Hunt’s latest book is an elegy for a lost generation

- Share via

Book Review

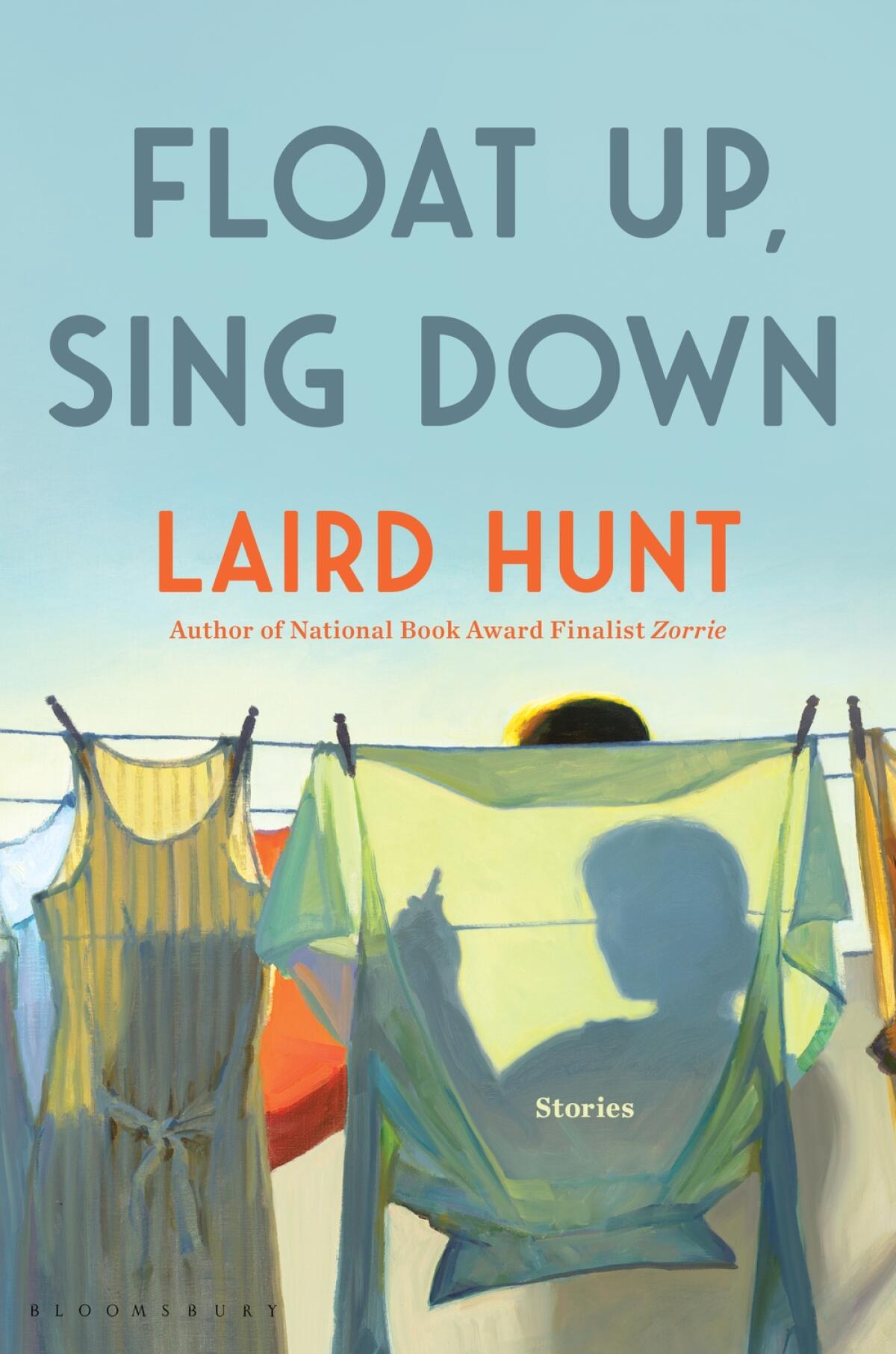

Float Up, Sing Down

By Laird Hunt

Bloomsbury Publishing: 224 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

A little more than a century ago, Sherwood Anderson’s “Winesburg, Ohio” introduced a new kind of American novel: one composed of short stories that share a setting and that elevate, one by one, individual residents for our examination. It’s proven a durable and appealing structure, whether employed by fellow Midwesterner Ray Bradbury in “Dandelion Wine” or Mainer Elizabeth Strout in her “Olive Kitteridge” novels. There’s an inherent, Where’s Waldo-style thrill in spotting one story’s main character as an incidental background player in another person’s drama. And it’s structurally both modernist (Gertrude Stein was an influence on Anderson) and democratic: everyone matters, from the outcasts to the losers to those who seem simply too plain for literary attention.

But the form is not without risk. Thornton Wilder, whose “Our Town” is the most famous dramatic inheritor of Winesburg’s legacy, cautioned in his stage directions that the play “should be performed without sentimentality or ponderousness — simply, dryly and sincerely.” When “Dandelion Wine” came out, a critic charged Bradbury with that exact sin, panning him for “diving with arms spread into the glutinous pool of sentimentality.”

Laird Hunt’s new book, “Float Up, Sing Down,” resists that dive (although there is a pool present, unavoidable in mid-July in Indiana). Following 2021’s “Zorrie,” a finalist for a National Book Award in fiction and a novel that itself borrowed characters from the author’s earlier “Indiana, Indiana,” the book is a Winesburg-style story cycle set in small-town Indiana during a single summer day in 1982. Zorrie Underwood makes a cameo or two, but unlike in the novel she anchored, these stories work like a core sampling of the entire community: a rural village surrounded by cornfields, where nearly everyone has memories of a farmhouse their grandparents inhabited — almost none of whom are still full-time farmers. Bright Creek is big enough for a high school, small enough that the school still sits at the center of the town’s stories about itself.

And, like a lot of Midwestern small towns in the Reagan ‘80s, its glory days are behind it. We meet many of the old guard in the book’s first story, in which retired teacher Candy Wilson prepares to host a monthly meeting of the Bright Creek Girls Gaming Club. “Cheating was tolerated though not openly encouraged” by the club’s “girls” (all in their 60s and 70s save the youngest). Candy, Lois, Gladys, Myrtle and the others gamble, snack and gossip, and subsequent stories open up into the lives they’ve lived, their private dramas, the secrets they keep.

Candy misses her friend Irma Ray, the town’s French teacher who’d lost her job for being “different.” The club meeting coincides with the first anniversary of her funeral, and Candy visits Irma’s grave, where the Latin phrase “Astra inclinant, sed non obligant” (“the stars incline us, they do not bind us”) is chiseled into the stone.

In ‘Alphabetical Diaries,’ Sheila Heti has once again tried something that feels impossible: collecting her personal diary entries for more than 10 years, re-ordering the sentences in alphabetical order, to build a different form of narrative.

Questions of fate and identity meander through these stories. Where we are born and into what kind of family matters — Hunt’s characters are not self-created in the manner most modern Americans like to think we are. The ripple effects of an abusive father, an indulgent mother, early success that fizzles — all guide a life’s path, sometimes quite literally, as when Gladys Bacon embarks on her occasional long, solitary walks through miles of cornfields (her friend Myrtle calls it “the corn cure”). She only does it on days, “when the sun angled long and blazed everything up in a glory of green and gold.” If there’s a more Midwestern way to manage existential pain, I haven’t heard it.

The old men too have their say. Horace Allen, who served in France on D-day and still pines for a European woman he met while recovering from war wounds, has retired from farming but still takes pleasure in his lawn care that binds him to the land (“the rake was like a metronome. The earth was like a clock.”) Some time after returning from the war, Horace had made a pile of white rocks behind his barn, a kind of altar to things lost. “When his parents died, he had stopped going to church,” Hunt writes. “He still sometimes picked up the Bible though. He was not against any of it. Sometimes he had gone out to the pile of white rocks and bowed his head.”

And then there are Bright Creek’s young people, working fast food and experimenting with sex and desperate to get out of there: We see two of them on the back of a motorcycle, “roaring up the road, burning up the map, being idiotic and beautiful and fifteen” toward the book’s end. Why shouldn’t they want to leave? After all, this is a place where a lesbian teacher is run out of town, where artistic inclinations of any kind are most safely kept to oneself. And yet, as one of the teenagers feels while riding her Schwinn as fast as she can down a country road, “the world smelled like corn and chicory flower and drying dirt and woods.”

When I moved to Boston from Kansas, nearly all my new friends referred to my having “escaped.” As Hunt makes clear, there are plenty of good reasons one might want or need to escape from a small Midwestern town. But his tender attention to these lives reveals that what’s there, good and bad, is as real as any of the stories painted on bigger canvases.

And somehow, without even the slightest sentimentality about it, the book provides an elegy for a lost generation, or maybe for all the elders still here, as overlooked as the Midwest itself. As Myrtle notices her own mouth hanging agape with age, she thinks that she “never minded that look. Both her grandparents had worn it plenty as they were rounding the final bend. Myrtle thought it made a person look astonished. Like they were thinking on some great wonder. Something marvelous. A memory they were the only ones in the whole big world to have.”

Tuttle is a book critic whose work has appeared in the Boston Globe, the New York Times and the Washington Post.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.