Star-crossed lovers torn apart by a cult: How a new novel humanizes the Waco siege

- Share via

On the Shelf

We Burn Daylight

By Bret Anthony Johnston

Random House: 352 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

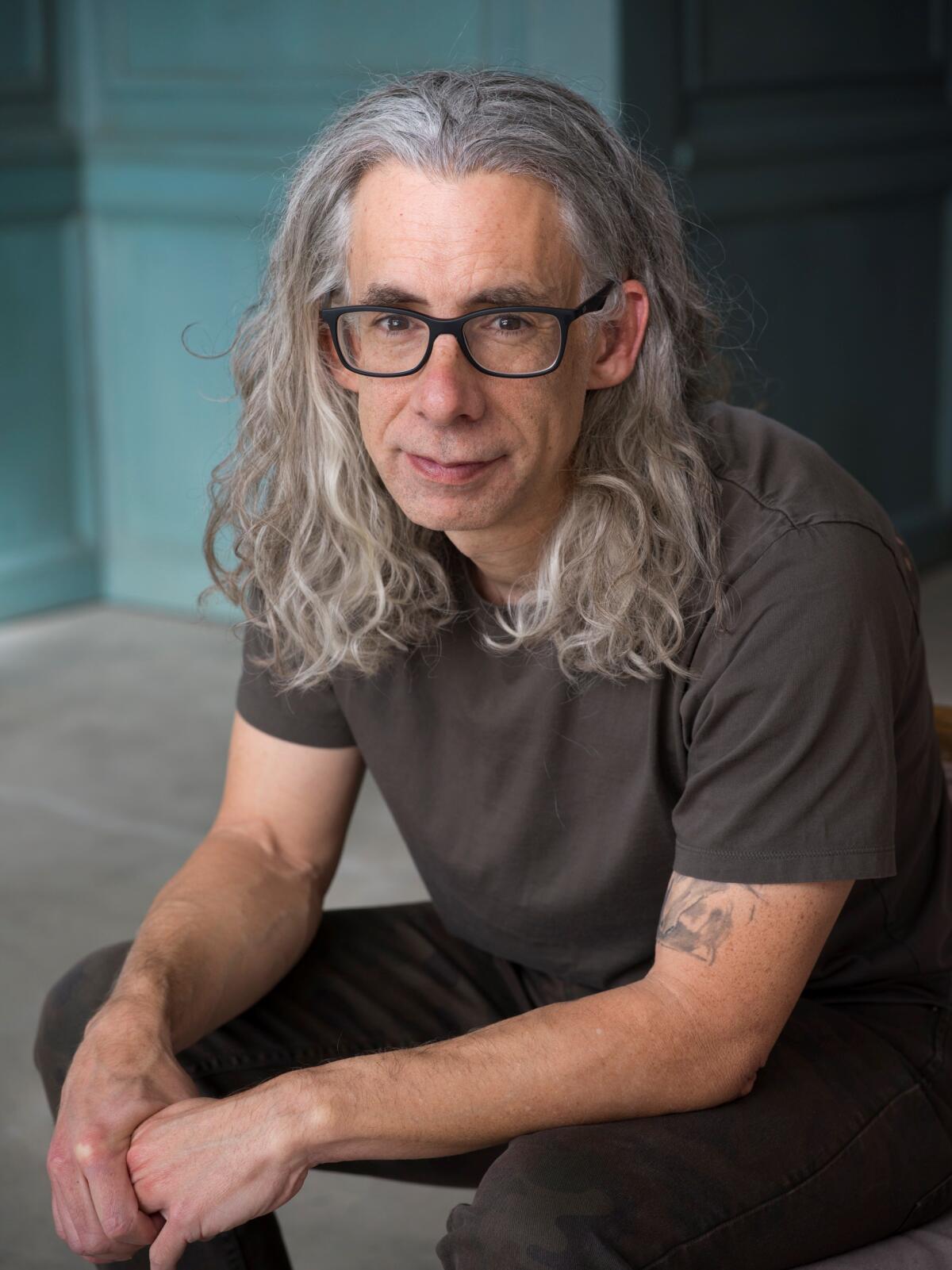

Novelist Bret Anthony Johnston was in his hometown of Corpus Christi, Texas, when the news came from outside Waco, about 300 miles away. A 51-day standoff between federal agents and followers of the messianic David Koresh had ended in a cataclysmic blaze. Eighty-six people, including those involved in the shootout that began the siege, were now dead. Johnston, like so many who had watched the April 1993 tragedy unfold on the news, was baffled and distraught.

“I felt like we weren’t getting the whole story,” Johnston said in a recent interview discussing his new novel inspired by the tragedy, “We Burn Daylight.” “I just felt deeply sad, and I felt a lack of trust. It’s all anybody was talking about. Half the people you met were saying they deserved it, and the other half were heartbroken and confused.”

Johnston was just a 21-year-old, skateboard-happy community college student at the time, still years away from publishing his acclaimed first novel, “Remember Me Like This.” But the uneasiness stayed with him, even as more information trickled out over the subsequent decades. He is fond of an adage from the great historical novelist E.L. Doctorow (“Ragtime”): “The historian will tell you what happened. The novelist will tell you what it felt like.”

With “We Burn Daylight,” out Tuesday, he aims to do just that — not through his own eyes, but from the perspective of two teenagers, madly in love and, through little choice of their own, on opposite sides of the Waco line.

Roy is the local sheriff’s son, a lonely high school student who picks locks as a hobby and misses his older brother, who stuck around as a contractor in Iraq after the first Gulf War. Jaye came from Southern California to the compound outside Waco with her mother, who grew enthralled with a charismatic, scripture-quoting young preacher named Perry — the novel’s Koresh stand-in — and joined his flock in the middle of nowhere, in search of salvation.

Roy and Jaye meet at a gun show in Waco and are immediately smitten. They are also, of course, doomed. The novel takes its name from words spoken by Mercutio to Romeo in “Romeo and Juliet” — “Come, we burn daylight, ho!” — and is, like Shakespeare’s tragedy, a story of star-crossed lovers who fall victim to circumstances beyond their control.

Johnston had no interest in relitigating the Waco tragedy or dissecting the ins and outs of what actually happened. Several nonfiction books report on the real events, including Jeff Guinn’s excellent “Waco,” published in 2023. Instead, he said, “I felt overwhelming curiosity about what it would feel like to be on the periphery of that, but still have it consume your life. I wondered what it would be like to have a crush on a girl and not know anything about her, and then everything you find out about her is the last thing that you want to hear.

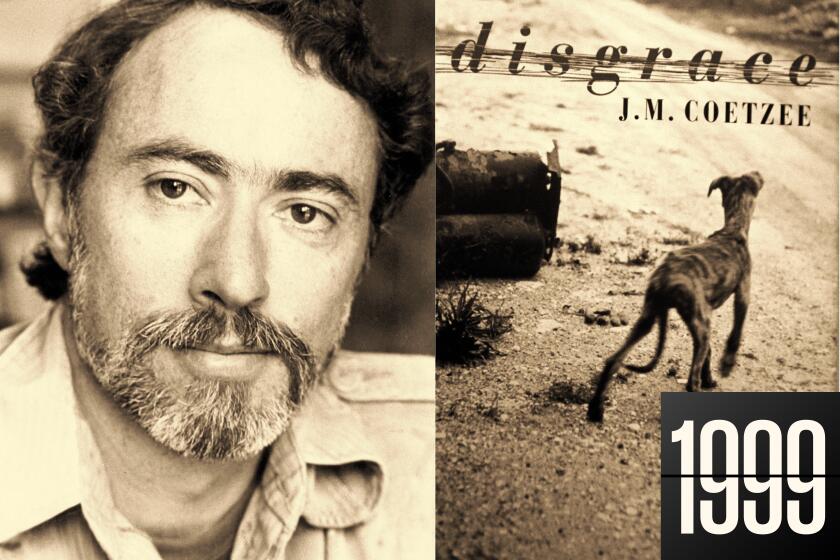

South African author J.M. Coetzee’s Booker Prize-winning ‘Disgrace’ stacks crisis atop crisis — and depicts its characters learning to live with it anyway. Sound familiar?

“I tried to put Roy in a vice grip and just keep tightening it.”

Johnston, a youthful 52, has flowing salt-and-pepper hair and wears a T-shirt emblazoned with the logo of Thrasher magazine, the longtime skateboarding bible (“I’m going into my 40th year skateboarding now,” he said. “It’s always painful”). He’s in his office at the University of Texas at Austin, where he’s the director of the Michener Center for Writers.

Growing up, he said, “I was mostly writing essays for school or knock-off Jim Morrison poetry.” Then he went to a reading by the novelist Robert Stone (“Dog Soldiers”) in Corpus Christi. He was mesmerized. A light went on: He wanted to write fiction. Before long he was getting his Master of Fine Arts at the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop. His debut short story collection, “Corpus Christi: Stories,” was published in 2004.

But Waco still gnawed at him. In 2010, when he was promoting “Remember Me Like This” in Houston, he met a man who had a co-worker who was killed in the fire. “He didn’t know that this person was going back and forth from the ranch,” Johnston said. Johnston became consumed by a question: “What would it feel like to see the face of this person that you’ve worked beside on the news after they’ve passed away in this horrible fire?” This was the seed of “We Burn Daylight.”

The story of why Priyanka Mattoo quit her job as a Hollywood agent to pursue a career in writing has as many twists and turns as her literary debut, the memoir ‘Bird Milk & Mosquito Bones.’

To Andy Ward, Johnston’s editor and the publisher at Random House, “We Burn Daylight” manages to humanize a story too often reduced to sensationalist headlines and rancorous debate.

“He made it feel fresh and new to me, and he made me think about what had happened in a way that I’d never thought about before,” Ward said. “He brought a lot of empathy and understanding and compassion to this story. At times he even made me forget it was even inspired or based on something that really happened.”

Johnston signals that “We Burn Daylight” is meant to be read as a work of fiction on the very first page, when Roy refers to “the March fires” (the real conflagration was in April). But he also strives for what could be called a veracity of the imagination. Chapters narrated by Jaye and Roy are interspersed with transcripts from a fictional podcast, “On the Lamb” (Perry, like Koresh, refers to himself as the Lamb, a frequently used name for Jesus Christ). Johnston had been writing fictional interviews with fictional survivors and others connected to the siege. It wasn’t until he was almost done writing that those interviews took the form of a podcast and entered the book.

The interviews, some friendly, some contentious, give the novel a polyphonic feel, a sense that the discussions and arguments continue to this day. They also helped Johnston acknowledge the reality of what happened 31 years ago, even as he plies the novelist’s craft. Departing from the hard facts, he stays true to the emotional heart of the story.

“I tried to honor the gravity of it,“ he said. “At the end of the day, I was more interested in authenticity than accuracy.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.