Joan Didion’s ‘Notes to John’ may be a gift. And yet, I wish her the privacy she relished

- Share via

Book Review

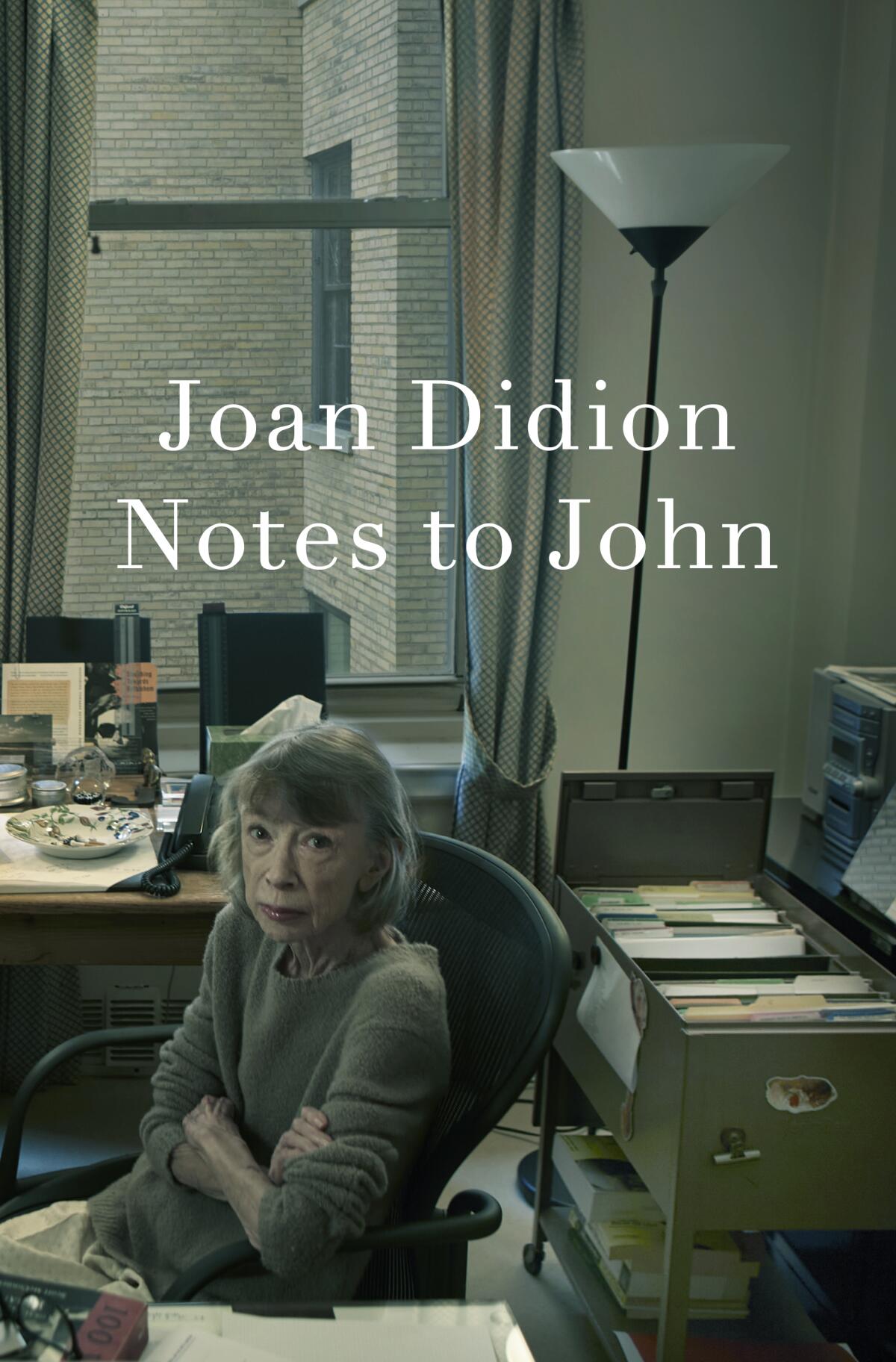

Notes to John

By Joan Didion

Knopf: 224 pages, $32

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Joan Didion’s persona has loomed as large as her literary canon. That photograph of her holding a cigarette just so, daring the camera to reveal what she’s thinking, says it all: You will be unable to find the key to the puzzle that is me.

The memoirs Didion published after the deaths of her husband, writer John Gregory Dunne, and their daughter, Quintana — “The Year of Magical Thinking” (2005) and “Blue Nights” (2011) — are her most personal, excavating her grief to produce works that are by turns deadpan, wrenching, restrained, operatic. She is excruciatingly introspective but in perfect control of every sentence and emotion — withholding, sparing or repeating words to produce observations that gleam with intelligence and insight but keep their author shadowed.

Didion died in 2021 at 87, and her literary trustees authorized the publication of observations she documented during an especially fraught personal period when she was seeing a psychiatrist to navigate her daughter’s alcoholism and possibly suicidal tendencies. Those sessions are capsulized in “Notes to John,” journal-like entries that were addressed to Didion’s husband, who was mostly absent from the appointments.

Didion’s therapist — a strict Freudian named Roger MacKinnon — was in regular communication with Quintana’s shrink. MacKinnon shared information gleaned about Quintana with Didion, unbeknownst to Quintana. It appears as though MacKinnon never met Quintana, and yet he doesn’t hesitate to characterize her codependency, or to interpret certain behaviors as manipulative, or to dismiss Didion’s fear that she might take her own life. When Didion expresses guilt that her adopted daughter is in such a “labile” state, he offers:

“Don’t take all the blame on yourself, she’s a very difficult person, a very hard case.” “You feel imprisoned by responsibility for her,” he intones. “You’re allowing her to hold you prisoner.” This serves to reassure Didion. Meeting after meeting, they repeat the theme: Quintana’s problems may have been exacerbated by the impenetrability of her parents’ bond, or by her mother’s tendency to distance. In MacKinnon’s words to Didion: “You rather spectacularly lack the skills for dealing with other people.”

The question haunting this book is whether an author so private that she revealed her breast cancer diagnosis to just two friends — Alice and Calvin Trillin — would have wanted her intimate, unedited reflections to be shared with readers. Close friends and family who have survived her appear split on this issue, with the majority coming down on the side of probably not. The document would have been made public in the archive she bequeathed to the New York Public Library, but if deposited there without the attention a book launch garners, they might have been relegated to obscurity.

Joan Didion fell in love with movies as a girl but would sour on Hollywood after working there, Alissa Wilkinson writes in ‘We Tell Ourselves Stories.’

Fame is no doubt a rare gift, but also cruel, with every bread crumb counting as an essential clue. I came away from “Notes to John” feeling discomfited and saddened — though literary scholars may read it as providing context with which to deconstruct a great writer’s oeuvre. To Didion’s Freudian analyst, the mother-daughter dynamic was everything, and the book suggests that the mother fell short. She professed love for Quintana, about whom she obsessed. But here she is ambivalent both about the maternal role and even, at times, about her daughter. She confesses to MacKinnon, “It had occurred to me at several points that I didn’t like her.” She says, “All my life I have turned away from people who were trouble to me. Cut them out of my life. I can’t have that happen with Quintana.”

From the outside, Didion seemed to be to be inscrutable, glamorous, insanely gifted and invulnerable. But Quintana, these pages reveal, saw her mother as “fragile,” if intimidating. How did Didion view herself? “A friend once remarked,” she writes, “that while most people had very strong, competent exteriors and were a bowl of jelly inside, I was just the opposite.” Her ethereal look masked her interior stoniness and likely facilitated her extraordinary powers of observation and reporting. This volume penetrates that shell to expose a woman entering her elder years as dealing with emergency rooms, hip fractures, vertigo and the necessity to shed the red suede high-heeled shoes and hoop earrings that distinguished her outward style. She continued to share details of her “late life crisis” until 2012 with MacKinnon if no one else, well after Quintana and John were gone, and 10 years after she stopped documenting their sessions.

Ultimately, “Notes to John” may be a gift. Didion broke barriers, refusing to feel remorse over valuing her career above all else and forging a language that can only be described as Didionesque. Should her insecurities and parental doubts be in the public domain? Most everything is now. She must have known that, as an icon, her life would be studied from every angle for decades to come. And yet, I wish her the privacy she relished. But these latest revelations only thicken the mystery: Who was Joan Didion?

Haber is a writer, editor and publishing strategist. She was director of Oprah’s Book Club and books editor for O, the Oprah Magazine.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.