Apple and Amazon could dominate Hollywood if they wanted to. Why they haven’t, yet

- Share via

This is the May 31, 2022, edition of the Wide Shot newsletter about the business of entertainment. If this was forwarded to you, sign up here to get it in your inbox.

Since Apple and Amazon first dipped their toes into the film and television business, there’s been an understanding among people who make movies and TV shows that these companies — with their massive clout and resources — could dominate Hollywood if only they wanted to.

Do they want to?

Apple became the first streaming company to win the best picture Oscar with its $25-million acquisition of “CODA.” Amazon bought MGM for $8.5 billion, adding to its existing film and TV operation. These are not small feats.

But, so far, the tech takeover of the entertainment business has been surprisingly modest.

Apple is releasing a dozen or so original movies a year, which is less than what Lionsgate distributed theatrically pre-pandemic. MGM gives Amazon a substantial film and TV library, but relatively little in terms of new franchises. MGM’s share of the domestic box office in 2019 and 2021 was about 2% and 7%, respectively, according to data from the Numbers.

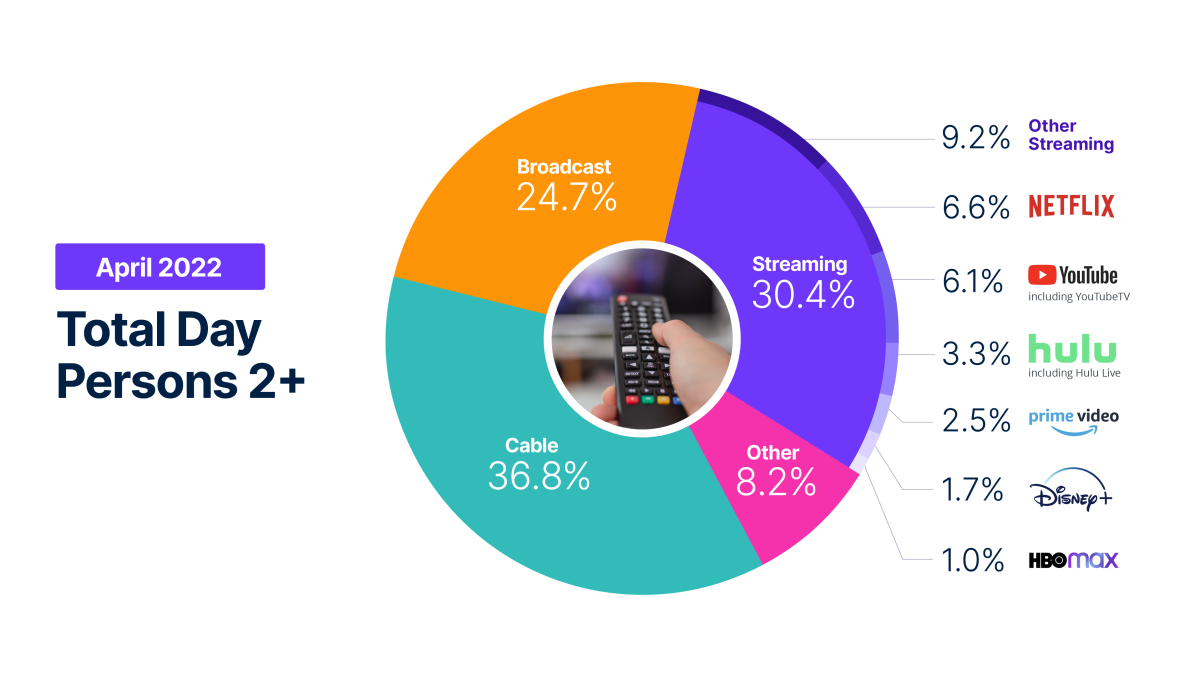

Amazon Prime Video accounted for 2.5% of U.S. TV viewing in April, compared with 6.6% for Netflix, Nielsen data show. The measurement firm includes Apple TV+ in “other streaming” because the service accounts for less than 1% of viewing.

This doesn’t necessarily reflect a lack of success. It could just be the tech firms’ methodical nature. Early success can create a sugar high that leads companies to grow too fast. But the likes of Apple Chief Executive Tim Cook and former Amazon Chief Jeff Bezos (succeeded by Andy Jassy) have resisted the siren song that has previously wrecked outsiders like AT&T and AOL.

Netflix’s recent stumbles have shown the risks of growing as fast as possible, and there’s much anxiety that budgets across the business are going to clamp down. The more traditional media companies are becoming more selective, as indicated by reports of Warner Bros. Discovery scrutinizing its $250-million deal with J.J. Abrams’ production company Bad Robot.

If the hope was that the tech titans would become the new blank-check scribblers for Hollywood, there’s bound to be disappointment.

“Outsiders almost always get burned, and I think these tech guys are savvy enough to know that,” said Stephen Galloway, dean of Chapman University’s Dodge College of Film and Media Arts. “We’re always looking for endless supplies of money from outside. But money is not endless, as they know.”

So why are they in the entertainment business, anyway?

The businesses of Apple and Amazon couldn’t be more different from Netflix, which essentially has one source of revenue — subscriptions.

Amazon generated $469 billion in its most recent fiscal year from its e-commerce and cloud computing businesses. Apple’s $192 billion in iPhone sales in fiscal 2021 dwarf the global theatrical box office. These companies don’t need to be in the movie and TV business. But here they are.

The point of Amazon Prime Video is to keep Prime on customers’ smart TV screens and sweeten the deal for the subscription delivery offering, which recently hiked its monthly fee from $12.99 to $14.99. The idea of Amazon’s “flywheel” is that giving customers a better experience improves traffic, which fuels the rest of the business. Entertainment is part of that.

In keeping with its image as the “everything store,” Amazon’s tastes have gravitated from its early highbrow niche phase (“Transparent,” “Manchester by the Sea”) to more middle-of-the-road fare like “Jack Reacher.”

The Apple TV+ strategy is similar, though it lacks a robust catalog of licensed older titles like Amazon’s.

Apple’s video service exists to help keep customers using the company’s products and to better monetize its install base of 1.8 billion iOS devices. Apple’s services division, which includes Apple TV+, is a growing part of the company’s overall business as the Cupertino firm diversifies. At $5 a month, Apple TV+ is not trying to compete with Netflix.

Its Apple Store locations are not just powerful marketing tools for “CODA” and “Severance.” They’re a way for Apple to tout its focus on quality. One reason the company doesn’t make dozens of movies a year is that it’s extremely difficult to make sure seven movies in a given year are any good, let alone 70. It’s why Apple historically has kept its hardware lineup mostly free of clutter. Someone who buys an iPhone knows what they’re getting.

Thus, Apple wants its film and TV selections to strike a certain balance: premium quality and broadly appealing without pushing the boundaries of taste. “CODA,” “Ted Lasso,” “Severance” and “The Morning Show” are prime examples.

They’re making moves to step up their efforts

Both companies are making major bets and spending serious dough.

Wedbush Securities analyst Dan Ives expects Apple TV+, helmed by Jamie Erlicht and Zack Van Amburg, to increase its content budget to more than $12 billion next year, compared with its current annual spending of roughly $6 billion to $7 billion. Amazon Studios, run by Jennifer Salke, has a reported content budget of $8 billion to $10 billion, and that is expected to increase.

“They decided to build it brick by brick,” Ives said. “I think shareholders want tech giants like Apple and Amazon to judiciously build it out, not just throw money at all costs.”

That said, Netflix’s stumbles have given them an opening. “Eventually, there was a fear that we would get to this moment where the hyper growth story for Netflix would strike midnight,” Ives said. “This is their time to shine.”

Apple is taking a giant swing with Martin Scorsese’s “Killers of the Flower Moon.” The company recently inked a lucrative pact with tech heir David Ellison’s Skydance Media. Amazon is gambling with “The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power,” which is expected to debut in September. Amazon and Apple have been acquiring rights to live sports, eating into cable and broadcast television territory.

As is always the case during times of disruption, there’s been rampant speculation about whether certain high-profile and out-of-work film executives might land at one of the big tech players.

Amazon has to figure out who’s going to run MGM’s film arm after the departure of Michael De Luca and Pamela Abdy. But Prime Video head Mike Hopkins is in no hurry, and the names in the rumor mill change week to week. Apple already has a head of original film in Matt Dentler, who reports to Erlicht and Van Amburg.

The big remaining question is whether streaming companies will more fully embrace movie theaters. Hopkins has said MGM will increase its theatrical film slate. Leaders of the major movie theater chains say there have been discussions with the major streaming services to bring more movies to the big screen.

Streamers already put their bigger movies in theaters, but they get a very limited rollout and don’t report box office numbers. Going further,the AMCs and Regals of the world would require the tech folks to agree to a window of exclusivity for cinemas, meaning they couldn’t put films on their services until 45 days or so after their big-screen debuts.

We will see. Theatrical releases require tens of millions of dollars in marketing and come with reputational risks. It looks bad when a studio tries to make a film into a must-see event and the movie bombs at the box office. Tech companies aren’t going to dive into that business willy-nilly.

“These guys invest in growth businesses,” Galloway said. “They created growth businesses.”

As successful as “Top Gun: Maverick” is, it doesn’t make theatrical film a growth business. It’s kind of the opposite of one.

Stuff we wrote

— The Amber Heard-Johnny Depp trial turned this ex-L.A. prosecutor into a YouTube star. Anousha Sakoui profiles Emily D. Baker, the former Los Angeles deputy district attorney turned YouTuber whose livestreamed commentary drew audiences surpassing that of mainstream outlets like Fox or “Entertainment Tonight” on the platform.

— Caruso vs. Katzenberg: L.A. titans — mayoral candidate Rick Caruso and DreamWorks Animation founder Jeffery Katzenberg — bicker over “lying” and bullying as the election nears.

— Disney power broker is part of a “cabal” pulling the strings in Anaheim, FBI records show. An FBI affidavit made public last week identified an employee of an influential, unnamed company as being a key participant in a “cabal” steering Anaheim’s government. Company A is Disneyland Resort, according to a person familiar with the investigation, and the employee is Carrie Nocella, Disneyland Resort director of external affairs.

— More headlines: Landmark Theatres chain takes over Laemmle’s Playhouse 7 in Pasadena. Explaining Hollywood: How to get a job as a production designer. After layoffs at Netflix, questions mount over diversity efforts. Former White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki joins MSNBC this fall.

Sheer chart attack: Netflix churn

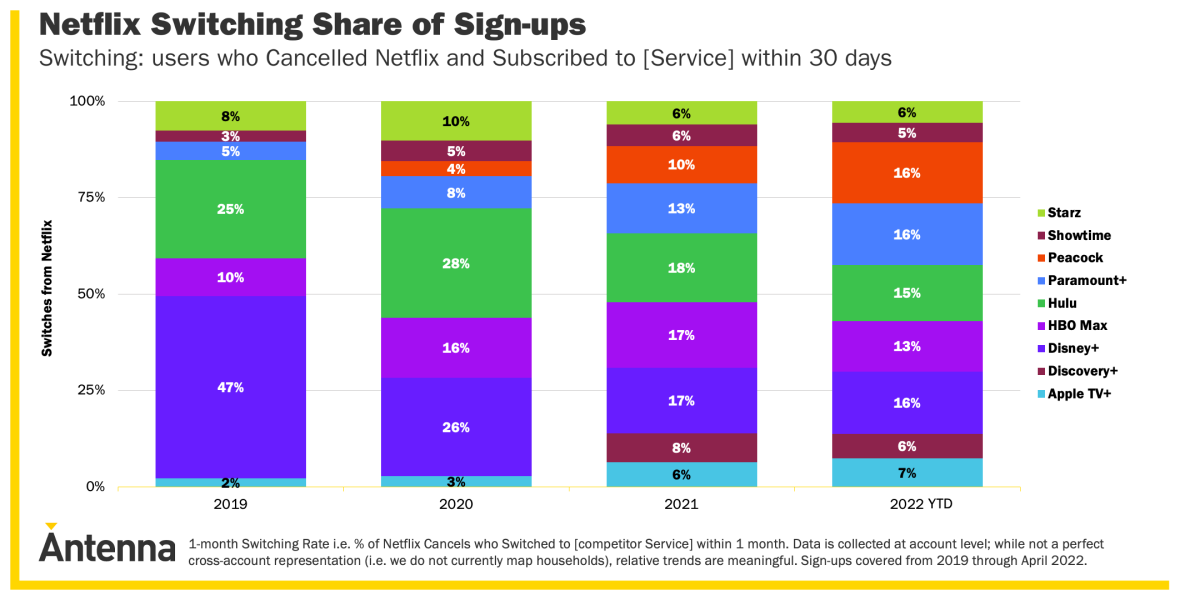

Netflix’s subscriber losses may be benefiting rivals, according to new data from Antenna, which uses transaction data to measure churn for streaming services. The data lend credence to the notion that Netflix’s slowdown is due at least in part to heavy competition.

The analytics firm found that streaming video services enjoyed increases in subscribers who recently canceled their Netflix memberships. During the first quarter, rival services saw an increase of more than 35% from the fourth quarter in terms of new subscribers who had canceled Netflix in the last 30 days. Paramount+, HBO Max and Peacock appeared to benefit most from Netflix’s struggles.

![A bar chart has the headline "Switching from Netflix to [Service]."](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/b1d3425/2147483647/strip/true/crop/2160x1080+0+0/resize/1200x600!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F89%2F04%2Fff0b720c46e8938e35b4f333ddbf%2Fantenna-chart-netflix-churn-1.png)

Number of the week

“Top Gun: Maverick’s” $156-million domestic box office debut over the four-day Memorial Day weekend is a win for Paramount Pictures and movie theaters.

This doesn’t mean that theaters are back to full health, but it does mean there’s hope that this can be a healthy business for certain kinds of movies.

The question is whether non-action tent-pole films can still work. Judd Apatow may have been right on the “Pivot” podcast when he argued that great movies can still work in theaters, even in struggling genres like comedy. As in an elite flight school, though, mediocrity is never going to cut it.

You should be reading...

— Angela Fu explains why the BuzzFeed News Union’s contract includes protections from ghosts. (Poynter)

— Mary McNamara on why Tom Cruise is, in fact, not the “last movie star.” (Los Angeles Times)

— Anthony Breznican on the televised future of “Star Wars.” (Vanity Fair)

— Jack Hough makes the case for Warren Buffett’s $2.6-billion Paramount investment. (Barron’s)

Finally ... a goodfella

Mark Olsen put it well when writing about actor Ray Liotta, who died last week at age 67 and will forever be known for “Goodfellas.”

“But even within that one part, the actor showed incredible range,” my colleague wrote. “As Henry Hill, who goes from cocky young street hood to a solid earner to a federal witness, Liotta had the underlying menace that would define his screen persona, but he also brought a tenderness and fragility — a lost, searching quality that made the character sympathetic even as his actions were often reprehensible.”

“Field of Dreams” is the other big Liotta role every obituary talks about, but he was also great in a couple of more recent projects, “Marriage Story” on Netflix and “No Sudden Move” on HBO Max.

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.