Inside the collapse of the company that brought indie movies to streaming giants

- Share via

In 2017, Burbank-based indie filmmaker and producer Alex Ferrari, 45, was singing the praises of a small tech company that helped him self-distribute his movie “This Is Meg,” about an actress struggling to navigate social media-obsessed Hollywood.

For a fee, the Los Angeles-based company, Distribber, had gotten the low-budget movie onto video on-demand sites including Amazon.com and Hulu. Thrilled with the results, he invited Distribber executives onto his podcast, Indie Film Hustle, and recommended the service to others. Here was a company, he said, that could get your movie on the world’s biggest platforms, and best of all, you’d keep all the revenue generated from sales and views.

But the lovefest tuned sour. Ferrari in April paid Distribber to upload two clients’ films, only to find out in September that the company had collapsed. Distribber, he learned after multiple calls and emails to contacts there, had already closed its offices, leaving its filmmaker customers in the dark. The company’s chief executive, Nicholas Soares, had left, as had other top executives. The firm’s assets, he was told, were being liquidated.

Ferrari said he’s owed at least $4,000 by Distribber, and he’s not alone. He and others estimate that hundreds of filmmakers could be owed money, with potentially millions of dollars in unpaid royalties and fee refunds at stake. Ferrari’s Facebook page “Protect Yourself From Distribber” has more than 500 members, some of whom are indie producers and directors owed tens of thousands. Many of them say they haven’t been paid all year, even as their films remain available on steaming services.

“I really, truly believe this is a little Lehman Bros. in our business,” Ferrari said in an interview, referring to the investment bank that filed for bankruptcy in 2008. “This probably going to close little producers that can’t take this hit.”

Distribber, whose struggles were previously reported by IndieWire, started out a decade ago as a promising solution for do-it-yourself filmmakers working outside the traditional Hollywood system. The company charged filmmakers about $1,500 to get movies uploaded on each streaming platform and collected royalties on their behalf. Filmmakers used Distribber’s software to see how often someone bought or viewed a movie, and how much revenue it generated.

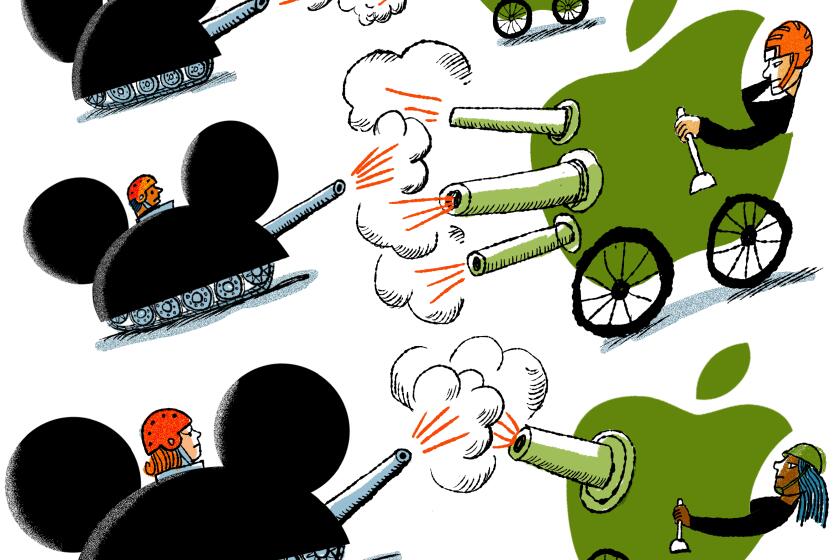

Disney takes on Netflix, as HBO Max, Peacock, Apple TV+ and Quibi prepare to enter the streaming fray. Not all will be able to thrive in the increasingly crowded market, analysts warn.

But behind the scenes, Distribber and its parent company GoDigital Inc. were struggling due to what multiple insiders and court filings describe as a flawed business model and mismanagement. The company’s practice of taking an upfront fee from filmmakers, rather than collecting a cut of royalties, forced it to continually chase new clients in order to stay afloat, said several people close to the company.

Compounding matters was a costly trail of litigation, including a contract dispute resulting in an arbitration award of nearly $520,000 against the company. A 2017 shareholder lawsuit described a culture of corporate waste and accused Soares and other officers of “taking lofty salaries” instead of paying down debts. The case was settled.

Multiple former employees, most of whom spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisals, said the company spent lavishly. Money was wasted on daily catered meals and equipment, including a 4K processing machine that required expensive software, said Jonathan Sheely, who worked briefly in the company’s accounting department until he was fired in 2017. He said he was sidelined after trying to improve its accounting methods for paying filmmakers.

“They were just hemorrhaging money,” Sheely said.

Soares declined to comment on Sheely’s claim, but denied allegations of corporate waste and mismanagement. “As GoDigital was a startup, I took a very small salary and did not accept one raise in 4 years as CEO,” he said in a statement to The Times.

The former CEO blamed the company’s demise on a bitter legal dispute with major business partners, including GoDigital founder Jason Peterson, whom he accused of fraud. Peterson disputed the claim. The legal battle prevented the company from raising capital, Soares said.

“In 2018, GoDigital discovered it had been defrauded out of a significant amount of money by its former business partners,” Soares said. “This led to a series of lawsuits which prevented GoDigital from closing on its B Round investment. GoDigital is currently suing these former business partners for over $10 million, and trial is set in 2020.”

Board members of GoDigital Inc., including “Jiro Dreams of Sushi” producer Kevin Iwashina, FreeCreditReport.com founder Ed Ojdana and former Facebook executive Chris Kelly, did not respond to requests for comment.

In September, the company hired GlassRatner Advisory & Capital Group, a subsidiary of financial firm B. Riley, to manage the disbursement of its assets through a third party. GlassRatner last week began sending letters to filmmakers saying it will be nine to 12 months before any funds will be distributed. It’s not clear what assets remain, or how much money will be available for the content owners.

“[We are] at the beginning stages of an accounting process involving thousands of titles,” said Seth Freeman, senior managing director of GlassRatner. “It’s too early to provide an indication of the amount that may be available to creditors, including content owners that are understandably anxious for this information.”

The downfall of Distribber has cast an unflattering light on an little-known part of the streaming industry that is supposed to make life easier for indie producers.

Companies like iTunes, Amazon and Netflix don’t want to deal directly with thousands of individual filmmakers submitting their micro-budget works. Instead, they work with a handful of film “aggregators,” including Distribber, which act as the middlemen between movie makers and online streamers. This cottage industry of aggregators optimizes movies for streaming services, providing technical services such as closed captioning and managing payments for filmmakers.

The years-old streaming skirmish has now become a pitched battle — for talent, for money, for your time and your eyes— as Apple, Disney, HBO and NBC to enter the fray with major subscription services.

Some companies, such as Santa Monica-based Filmhub, make money by taking a percentage of revenues generated by clients’ movies. Others, like Distribber and rival Quiver, charge an upfront fee.

Joe Dain, president of horror movie company Terror Films, which used Distribber for its movies, views its collapse as a cautionary tale for filmmakers. “What I’m trying to explain to people is that all we’re doing is jumping from one frying pan into another, because what happens when the next unregulated aggregator goes down?” said Dain, who would not say how much Distribber owes his company.

Distribber was founded in 2008, during the early days of the streaming revolution, by Los Angeles tech entrepreneur Adam Chapnick, who had previously launched another distribution firm called DocWorkers. (Chapnick left the company in 2014 and did not respond to requests for comment.)

In 2010, Distribber was acquired by Indiegogo, a popular resource for filmmakers to crowdfund projects.

Soares, 35, a tech entrepreneur hailing from a city near Fresno, acquired the business and became its CEO in 2014 with the goal of expanding its global reach.

In 2015, Distribber sold to GoDigital Inc., the former film distribution arm of tech holding company GoDigital Media Group. Soares became CEO of GoDigital Inc. after the acquisition.

From the outside, the Carthay Circle-based company seemed to be successful. Its website boasted that it had 4,900 customers and had paid $41 million to its clients.

But GoDigital Inc. and Distribber soon became embroiled in lawsuits with Peterson, a Marina Del Rey-based tech entrepreneur.

Peterson’s company Contentbridge in 2016 sued Soares’ GoDigital Inc. for breach of contract after the Distribber parent allegedly stopped paying Contentbridge for encoding services. GoDigital Inc. said Contentbridge was struggling to keep up with demand. An arbitrator awarded $520,000 to Peterson’s company.

Soares’ GoDigital Inc. countersued Peterson in 2018, accusing him and others of fraudulently inducing it into paying more than it should have for Contentbridge’s services. GoDigital was supposed to pay $17,900 a month starting in 2014. The complaint cited a 2012 email from Peterson in which he said he needed to “miss-direct” investors in order to reach a compromise on the monthly fee. Peterson denied the allegation, saying the email had been taken out of context. Peterson and the other defendants have filed a motion to dismiss the case, which is pending.

Peterson also has alleged that he and other shareholders were harmed by “corporate waste” and “gross mismanagement,” according to a 2017 lawsuit against Soares.

“They effectively froze us out,” Peterson told The Times. “We had no insights into what was happening at the business.”

Soares disputed the claims, and the case was settled.

Amid the legal battles, it became increasingly difficult for filmmakers to collect their payments from Distribber, said Sheely, the former GoDigital accounting department employee. Filmmakers who complained about the lack of payments got priority, he said.

“The squeaky wheels were the ones who got paid,” Sheely said. GoDigital was “smart enough to know how much we needed to owe somebody before they could take us to court.”

Meanwhile, filmmakers have been scrambling to have their movies removed from Amazon, Netflix, iTunes, Google Play and other sites. Content licenses with Amazon have already been terminated, according to a webpage set up for creditors.

Netflix has begun reaching out to filmmakers directly, an encouraging move for some, who hope that the Los Gatos streaming giant will pay them royalties even if they’ve already sent money to Distribber. Netflix, Amazon and iTunes declined to comment.

Ferrari, the filmmaker and podcaster, said he started the Facebook group about Distribber because he felt obligated to help his colleagues.

“There would be mad chaos right now if it wasn’t for this Facebook group,” he said. “People would be lost, and it’s my responsibility to help as much as I can.”

Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this article.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.