- Share via

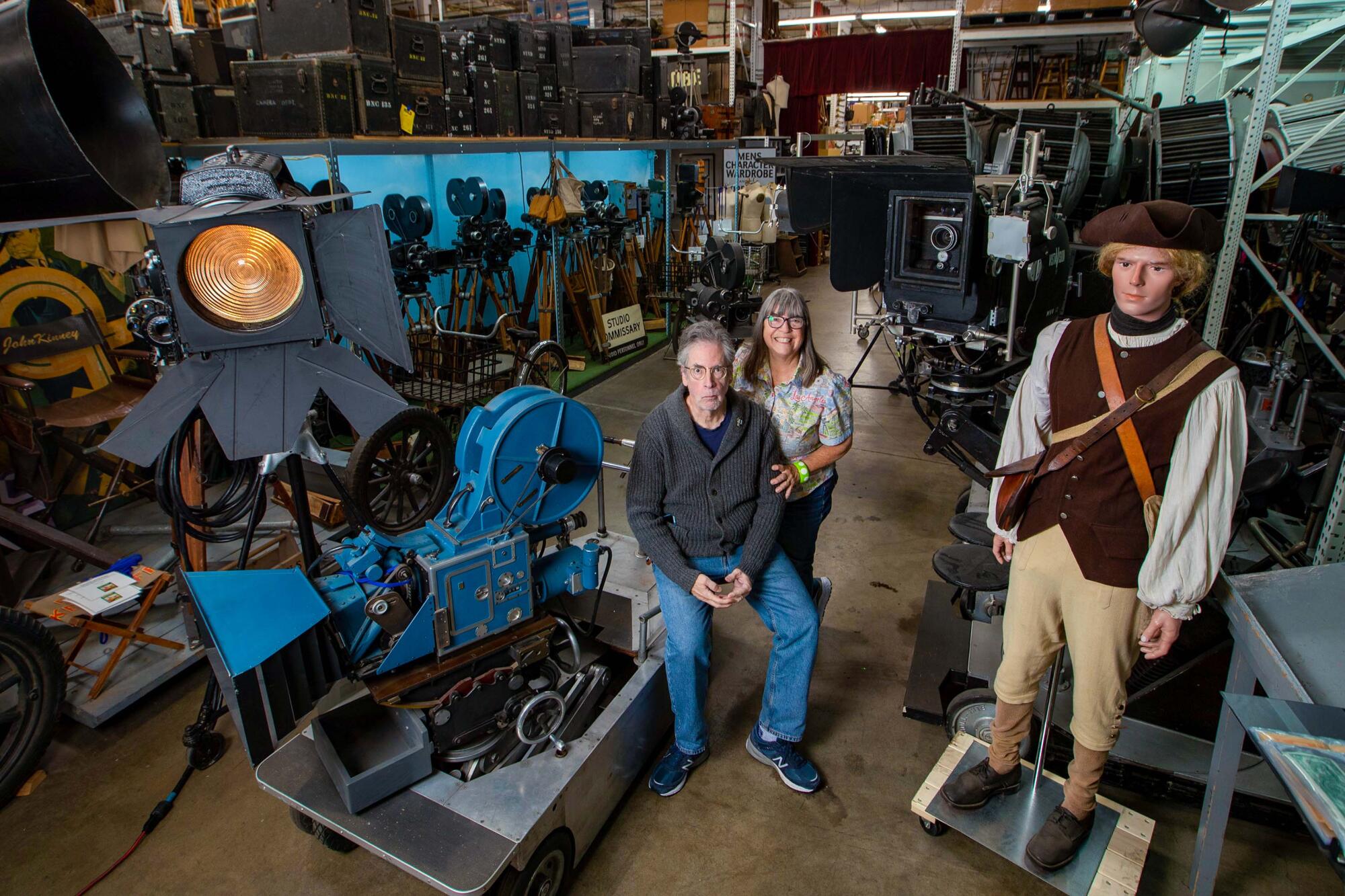

Last time there was a Hollywood writers’ strike, in 2007, the resulting halt in filmmaking activity depleted the savings of Pam and Jim Elyea’s prop house History for Hire, so much so that they had to defer a dream of owning their own warehouse.

Years later, COVID-19 brought another formidable challenge for their North Hollywood business, which has supplied props including period-appropriate luggage for “Titanic” and cameras for Steven Spielberg’s “The Fabelmans.”

Now history is repeating itself with a new writers’ strike that began on Tuesday, which is causing a significant portion of local production to shut down.

“COVID didn’t kill us,” Pam Elyea said. “I don’t want this to be the thing that kills us.”

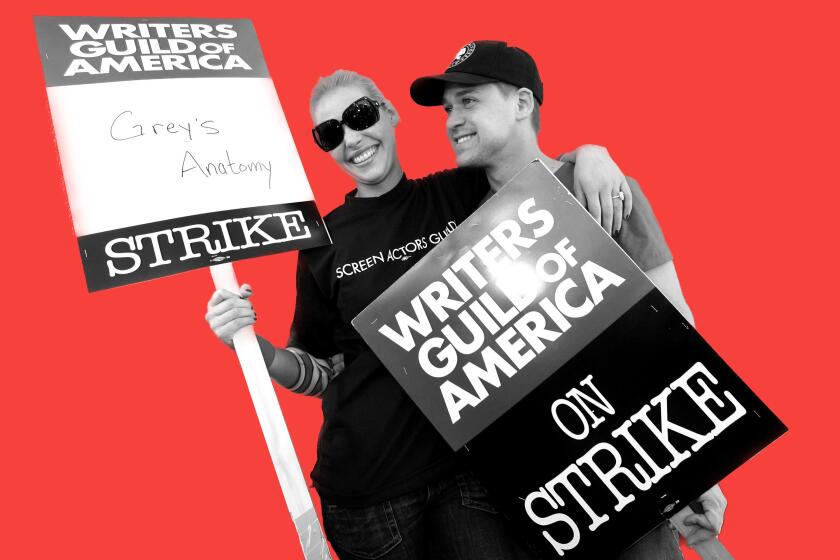

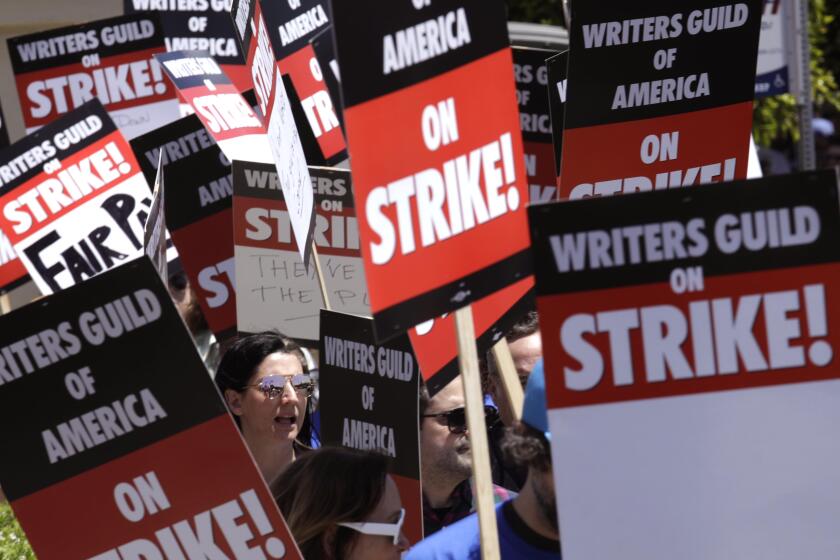

This week, the Writers Guild of America, which represents 11,500 members, hit picket lines to demand better pay and treatment after contract talks with the major studios broke down.

The 2023 writers’ strike is over after the Writers Guild of America and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers reached a deal.

Writers are seeking increases in minimum pay, better residuals from streaming and more contributions to the union’s health and pension plan. Many writers say that the streaming content boom has led to them getting paid less for more work.

Studios say they have made concessions on writer compensation and streaming residuals and have been willing to improve upon their offer, but have balked at the guild’s demands for mandatory staffing levels and minimum duration of employment.

With no resolution in sight, a protracted strike is likely to have unintended consequences for local businesses including florists, prop houses and caterers that supply film and TV sets with decorations, food and coffee to bring scripts to the screen.

Hollywood writers formed picket lines in L.A. and New York after the Writers Guild of America called a strike for better pay and working conditions.

Movies and TV shows can’t shoot without scripts. And while some shows banked screenplays ahead of time, production has already declined in recent weeks in anticipation of a strike. As the dispute drags on, analysts anticipate a greater downturn in the L.A. production economy, one of the region’s signature industries.

Crucially, the writers have the backing of fellow entertainment industry unions, whose members also stand to lose out on work because of the conflict.

The Directors Guild of America, SAG-AFTRA, which represents actors, and IATSE, the union for below-the-line crew members, have issued statements of support, as they face related issues in the streaming era. IATSE nearly went on strike in 2021 over issues with pay and working conditions.

The Teamsters, representing workers such as drivers and prop warehousemen, have declared “full solidarity” with the WGA, saying they “do not cross picket lines.”

Hollywood’s writers went on strike, but what were the issues that led to the fallout with the studios and streamers. Here are six issues where talks fell apart.

Nonetheless, having fewer movies and TV shows in the works reduces the demand for the services of small businesses that support those productions. While many in the entertainment industry support the writers’ goals, some business owners are worried about how they’ll pay their rent and staff.

History for Hire, for example, expects to lose six figures in revenue every month that the strike continues, Elyea said. Business is already down 40% compared to a year ago, while costs including rent, utilities and health insurance have gone up. The Elyeas laid off two people in March after business slowed down.

“Script writing is at the very beginning of many of these productions, but the downstream effect is tremendous,” said Scott Purdy, U.S. national media industry leader for audit, tax and advisory services firm KPMG. “Think of it as a conveyer belt that you hit the pause button on or hit the off button ... the economic impact has a bit of a multiplier effect.”

Many remember the 2007-08 writers’ strike, which cost the California economy an estimated $2.1 billion and 37,700 jobs tied to the entertainment industry, according to the Milken Institute.

Writers made important gains in compensation from digital video, then called “new media.” But makeup artists and lighting technicians lost work. Businesses such as hotels and dry cleaners also took a hit.

The overall damage will depend on how long the work stoppage lasts. The previous writers’ strike lasted 100 days. The WGA and the group representing the studios, the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, remain far apart on key issues, with the guild seeking improvements worth an estimated $429 million a year. The studios offered increases valued at about $86 million, according to the union.

Once the strike ends, it could take a while for business to pick up again, analysts said.

“The writers aren’t going to hand in a dozen scripts a day after the strike ends,” said Sanjay Sharma, a professor at USC Marshall School of Business. “You could be talking about a production lag of at least 30 to 60 days following the strike.”

The 2007-08 writers’ strike, and lingering mistrust between big media companies and their Hollywood workers, has cast a long shadow over current WGA contract talks.

The strike comes after many businesses managed to survive the pandemic. During that time, some business owners made changes to tighten expenses and looked for other ways to make money.

Adrianna Cruz-Ocampo, president of U-Frame-It Gallery, which supplies mirrors and picture framing to film sets, said there’s a candle at her house where she prays for an end to the stalemate. About 65% of her business comes from film and TV productions, including the recent Amazon Studios film “Air” and the sitcom “Young Sheldon.”

“I just hope that this is not too long because we’re just getting back from the pandemic,” Cruz-Ocampo said. “I think the timing’s awful.”

Hollywood writers on Tuesday formed picket lines in L.A. and New York after their union called a strike to demand better pay from streaming, as well as improved working conditions.

To adapt to this year’s strike, some businesses that rely on Hollywood could switch gears. Caterers that do craft services could, for example, turn their focus to live events, said KPMG’s Purdy.

“If they’ve got a little bit more of a diversified business, [they could] move into and lean harder into other customer segments that they’re currently serving to help bridge the gap,” Purdy said.

But for others, it’s not as easy to pivot.

Corri Levelle’s Sandy Rose Floral Inc. in North Hollywood provides floral arrangements for film and TV scenes including weddings and funerals.

Changing her business to provide flowers for real-life weddings would be challenging and would not help her immediately. Most actual weddings are planned six to 12 months in advance. All she can do for now is wait and hope the writers’ strike won’t last long.

“I just hope that both sides keep to the table and keep working on it,” Levelle said.

Wini McKay, co-owner of Jurupa Valley-based prop house L.A. Circus, plans to focus on businesses not affected by the work stoppage, such as events and music videos. To save money, L.A. Circus will delay refurbishing its props and repainting its trucks.

She called the strike “another sucker punch.”

Still, McKay said she respects unions and that it’s important for people to strike if they need to. “We’ll survive,” McKay said. “We survived the last one.”

Staff writers Ronald White and Karen Garcia contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.