‘Pain and Glory’ is Pedro Almodóvar at his best

- Share via

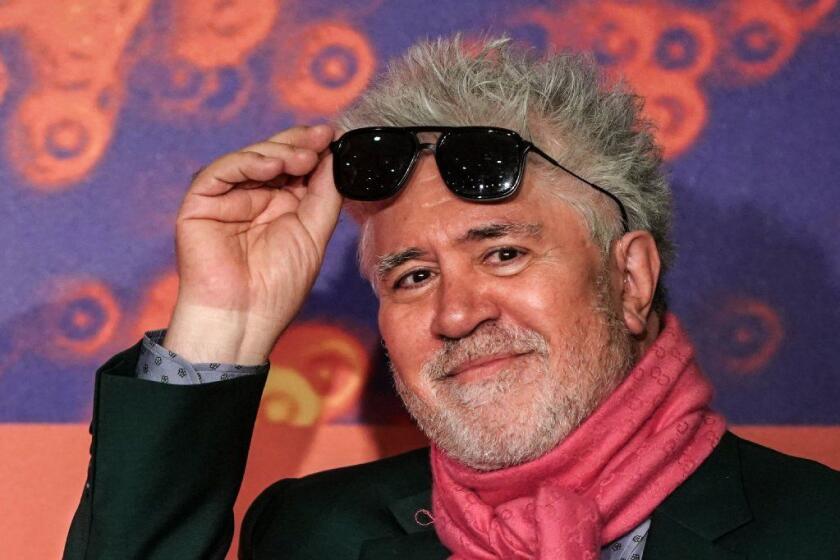

A surprise in all ways except its surpassing quality, “Pain and Glory” reveals master Spanish director Pedro Almodóvar forging dazzling new paths while being completely himself.

Dramatic rather than melodramatic, autobiographical but only around the edges, using Antonio Banderas in unexpected ways but skillfully enough to win him the best actor prize at Cannes, Almodóvar takes delight in contradicting whatever you might be expecting.

Yet on the other hand this at times austere story of an aging filmmaker (“a director with his aches and pains” in Almodóvar’s words) at a crisis point in his life is very much like the director in that very unpredictability.

Instead of the shocks of melodrama, a genre the filmmaker loves passionately, “Pain and Glory” is successful in the way its considerable classic emotional heft manages to sneak up and wallop you by the close.

Artfully set up in their own place and time by Almodóvar’s fluid screenplay, events that seem random turn out to be intimately connected, with the filmmaker himself emerging one more time as someone having way more imagination than we do.

A film with many touchstones, pain, memory and enduring love among them, “Pain and Glory” concerns itself most with the nature and influence of the creative impulse and the power of the past to revive and enlighten us in the present.

And, not surprisingly since Almodóvar has just turned 70, it both demonstrates and deals with how all things change with age, the regrets we have to live with and those we do not.

“This is the game,” Pedro Almodóvar says, his eyes positively twinkling as I apologize about asking an obvious question.

Given that Almodóvar has a considerable amount in common with Salvador Mallo, “Pain and Glory’s” filmmaker protagonist, including living in the identical apartment with the same art on the walls, it’s tempting to see this film as more autobiographical than it is.

But in an interview at Cannes the director explained this was not the case, noting that while for practical reasons “my own reality was the start,” invention inevitably became the order of the day.

Banderas, who has worked with the director on seven previous films, is the heart of things here, but his exceptional work is very different from the large, energetic performances that made him a Hollywood star. Even Almodóvar himself, despite his decades-long friendship with the actor, confessed at Cannes he wasn’t initially sure the switch was possible.

As it turned out, the actor’s Salvador Mallo expertly projects more stillness and gravitas than energetic brio. It’s a master class in restrained charisma that confirms that in the hands of a gifted performer underplaying enhances feelings in the most effective way.

Mallo is first met, of all places, standing stock still at the bottom on a Madrid indoor swimming pool (just the first of cinematographer José Luis Alcaine’s numerous arresting images.)

As a scar running the length of his back hints, and as we soon learn, Mallo is two years removed from spinal surgery but still in intense, debilitating pain.

Not only is being underwater easy on the back, it conjures the first of the film’s many luminous forays into enriching memory. The director reflects on his 9-year-old self (beautifully played by Asier Flores) hanging out with his mother Jacinta (Penélope Cruz one more time) as she and her friends wash sheets by the river near his boyhood home.

Leaving the health club, Mallo runs into an actress friend (Cecilia Roth, another Almodóvar veteran), telling her that though he feels he can’t live without directing, his back pain is so excruciating he may have to give it up.

Mallo also tells her that he’s just re-seen and enjoyed “Sabor,” a film he made 32 years earlier, and though he insists he doesn’t hold a grudge, he’s clearly still furious at star Alberto Crespo for acting choices made lo those many years ago.

But because the city’s cinematheque has restored “Sabor” and wants to have a gala screening, Mallo doggedly makes his way out to Crespo’s house to ask him to participate even though the two haven’t exchanged a word in the decades since their altercation.

Sharply played by Asier Etxeandia, Crespo is still angry as well, but at the moment he’s preoccupied with “chasing the dragon,” slang for smoking heroin off of aluminum foil. Mallo, who’s never indulged, decides to try it and even more memories result.

Times critic Justin Chang is filing regular dispatches from the 72nd annual Cannes Film Festival, which runs May 14-25 in France.

“Pain and Glory’s” central remembrance centers on the time young Mallo and his family moved to Paterna, in Valencia, in search of better times and ended up living in one of the city’s strange, cave-like underground dwellings.

It’s here that he meets Eduardo (César Vicente), a young laborer who he teaches to read and write in exchange for the handsome youth doing work around the cave.

Also coming into play is a reluctant decision by the adult Mallo to allow actor Crespo to turn “Addiction,” a short memoir he’s written about his life in the more recent past of 1980s Madrid, into a one-man theatrical show.

That all these disparate elements could appear in the same film, let alone coalesce almost magically by the close, may sound beyond belief, but Almodóvar, a filmmaker surely at the height of his powers, is up to the task.

“It’s a question of the passage of time,” he said at Cannes about his switch from melodrama to drama, adding puckishly, “This is because I am getting old.” Whatever the reason, the results speak articulately and movingly for themselves.

'Pain and Glory'

Rating: R, for drug use, some graphic nudity, and language

Running time: 1 hour, 54 minutes

Playing: Arclight, Hollywood; Landmark, West Los Angeles

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.