Judy Garland’s life was run by men. These newly unearthed recordings reveal how

- Share via

Deep in the San Fernando Valley, there is an unremarkable warehouse where some of the few remaining pieces of Judy Garland’s life are stored. They are kept in cardboard boxes and film cans, never subjected to temperatures above 65 degrees. The rare concert footage and home video recordings have barely been touched since their owner — the performer’s third husband and longtime manager, Sid Luft — died in 2005.

But Luft’s archives were recently, for the first time, made available to a documentary crew that partnered with the trust on a film about Garland’s life. “Sid & Judy,” which will debut tonight on Showtime, is like many portraits of the singer’s life in that it details the struggles she faced: her substance abuse, bouts of depression, five marriages and child custody battles. But by culling from Luft’s collection, the documentary offers a more unvarnished take on Garland’s life than, say, “Judy,” the scripted film currently in theaters that is earning star Renée Zellweger Oscar buzz.

Over the course of their 13-year marriage — Garland’s longest — she and Luft had two children together, and he remained her manager until she died in 1969 at age 47. He would later write about their relationship in a book that was eventually published in 2017. Though he was legitimately close to Garland, Luft was hardly the only one to publicly offer his take on the star. Among those who have written books about her: one of her daughters, Lorna Luft; her fifth husband, Mickey Deans; John Meyer, who said he had a two-month affair with her; and Mel Tormé, who served as the musical director on “The Judy Garland Show.”

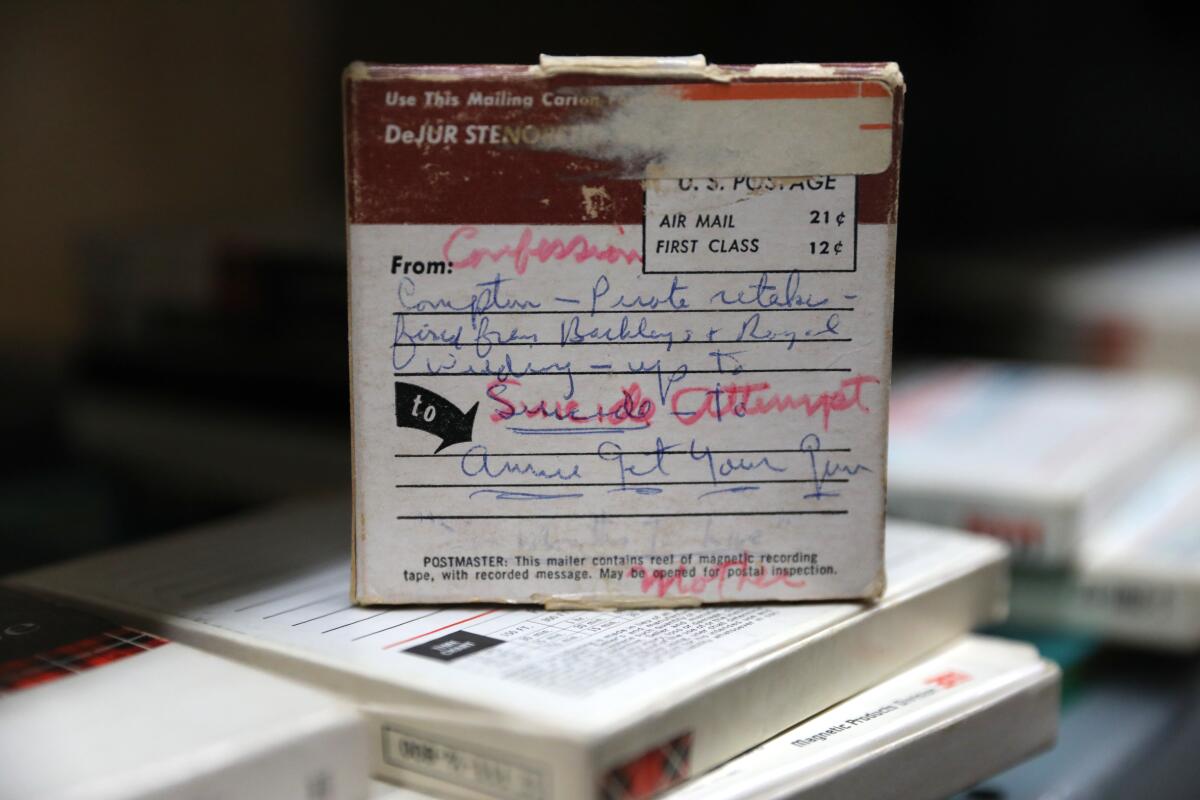

Garland was never able to tell her own story in full. Looking for a way to stave off financial ruin in the 1960s, she attempted to put together her own autobiography. Some of her writings, as well as tape-recorded dictation meant to be used for the book, are now part of a Columbia University archive.

We hear some of those recordings in “Sid & Judy.” But even through the voices of others, a fuller portrait of Garland’s life — wretched, heroic, unjust — begins to emerge.

Secretly recorded phone calls

Arguably the most astonishing material in “Sid & Judy” comes from the recordings Luft secretly made of his phone calls with Garland’s business associates. As their marriage began to disintegrate, Luft was fielding the blame for much of the singer’s financial trouble. To insure himself against negative claims, he began taping his personal conversations — without the consent of the other party.

“Everyone involved is dead, so I believe the statute of limitations is dead too,” said Stephen Kijak, who directed “Sid & Judy.” “He was primarily doing it because of his belief that her other managers were stealing from her. He was trying to be a little bit of a private eye. It really gives you a firsthand peek into what was happening. It wasn’t enough to hang the whole film on, but it really props it up.”

What is most revealing about the recordings is the way in which Garland is discussed as if she were an object instead of a person. In one October 1963 call with CBS programming executive Hunt Stromberg Jr., Luft is told about a “very, very unpleasant and unfortunate night” on the set of Garland’s musical variety show.

“I’m aware that when you you get in that state, you’re not responsible for some of the things you do,” Stromberg said. “But if somebody has leprosy, Sid — it is highly regrettable, but you stay away from them.”

“Certain people are getting her too much junk,” Luft responded, alluding to Garland’s pill addiction.

“It just reaches a point where you just say, ‘Aw, ... it!’” the executive said.

“Somewhere along the line, she got mixed up,” Luft lamented. “Maybe it was partially my fault. Maybe, uh, I mixed her up. I don’t know.”

Addiction battles

The documentary does not shy away from Garland’s lifelong battle with prescription medication and alcohol. In excerpts from his memoir — which are read in the film by Jon Hamm — Luft describes how the actress’ weight was “constantly monitored” from the time she was a young girl working at MGM.

“Amphetamines were commonly doled out by studio doctors,” he explained. “Amped up on bennies, she would be worked to near-collapse on films like ‘Girl Crazy,’ with director Busby Berkeley pushing her to the limit to complete his elaborate concepts. She had to be as alert and vital on the last take at 11 p.m. as she had on the first take at 9 a.m.”

In 1953, shortly after the couple moved into a plush mansion in Holmby Hills, Luft said Garland’s addictions nearly burned the house down. She was in the midst of shooting “A Star Is Born,” and one night, strung out, she passed out in a chaise and her cigarette fell to the ground.

“Judy was on bad pills,” Luft said. “She confessed. It was virtually impossible for her to sustain a work mode in front of the cameras without taking some kind of medication.”

Luft goes on to admit he was “enabling” her drug problem, coming up with a plan to employ an MGM doctor “for the length of the shoot to monitor her and keep her on an even keel.”

“In hindsight, I was enabling,” he reflected in his book. “A lesser version of what MGM had blatantly and inhumanly jammed down her throat.”

The roller coaster of addiction continued to upend the marriage. At one point, Luft said, Garland expressed a desire to go to Alcoholics Anonymous, but the couple made it to only one meeting in Pasadena. Later, they visited Narcotics Anonymous in a “room lit by spooky lights” that had “the atmosphere of an opium den.” Garland did not take to the environment, he said, declaring, “It’s enough to make a person want to stay bombed forever!” and heading to then-popular restaurant Romanoff’s for a cocktail.

When Luft tried to control Garland’s pill intake, she turned his “concern into a game,” he said, referring to him as “the cop, the narc, the flatfoot.” When he searched for medication within their home, he’d find pills hidden in cigarette cartons and Seconals in her bath powder. But when she was touring, he had a more difficult time controlling things. “On the road, she could score from anybody — a chorus boy, a musician, a hairdresser, a friend,” he said.

Garland would later die from an accidental barbiturate overdose while traveling in London.

A complicated romance

The relationship between Garland and Luft perplexed many in Hollywood, including those close to the couple. In one of Luft’s recorded phone calls, actor Andre Philippe told Luft that Garland referred to him as an alcoholic who never works and gambled away her fortune.

“Are you two still in love with each other? I don’t understand the whole relationship,” Philippe asked.

“Nobody will,” Luft replied. “Nobody ever will.”

At first, the film explains, their relationship was a slow burn. Luft even wrote in his memoir that he was “not attracted to her at first,” and in 1951 — before they were married — he reacted horribly when she told him she was pregnant.

“‘We’re putting on a show at the Palace and you’re coming to me with ‘our baby?’” he said, referring to the two-a-day performances Garland was doing in New York at the time. “I imagined the headlines: ‘Not divorced! Cancel the Palace! Luft’s illegitimate child!’ I handled it like a clod. I didn’t go with her when she had the abortion. I wasn’t attentive. I didn’t send flowers.”

Later, though, Garland and Luft would go on to have two children together — Lorna and Joey — and the singer would sometimes stay up all night and leave love notes for her husband to find in the morning.

“In spite of all my pukiness, I loved you all through the night,” she wrote in one message that is shown in “Sid & Judy.” “Not an attractive thing to tell you, but when you adore your husband, what are you gonna do?”

John Kimble, who manages Luft’s trust, said that even though “everybody thought Sid was the villain,” he was devoted to her. Kimble met Luft through his son, Joey, and they became friends. They kept in touch over the years, and in the 1980s, Kimble spotted Luft driving a brand-new Mercedes.

“I asked him, ‘How come you look so good?’ And he said, ‘Money,’” Kimble recalled. “He had acquired all the rights to the Judy Garland TV shows, and started making TV deals. So I asked if I could work for him.”

Toward the end of Luft’s life, the two had grown so close that they were going to lunch nearly every day, Kimble said, and Luft would “start crying as soon as he started talking about Judy.”

“He does get a bad rap, although we didn’t make this film to rehabilitate Sid Luft,” said Kijak, the filmmaker. “Of course, he’s going to see himself as sympathetic, but he did understand his complicit nature in all of this. Given their marriage of 13 years, he does have a certain authority, so his perspective is valid. We just wanted to make sure it didn’t overtake and manipulate too much.”

A man’s world

After Luft and Garland divorced in 1965, a friend attempted to comfort the performer by telling her she’d simply gotten involved with the wrong man.

“The wrong man?” she replied. “I’ve been involved with men in business all my life. One’s no different than the other. ... You’re all in the Judy Garland business.”

The degree to which men controlled Garland’s life — both emotionally and financially — is a strong theme in “Sid & Judy.” In one of Luft’s secret phone calls, film producer Freddie Fields tries to reassure Garland’s spouse that all of her troubles will be eased if she just keeps working.

“I honestly, I really now firmly, sincerely, deeply believe that the best thing for this girl’s health, security, mind, sanity, is to get back to work,” Fields said. “This girl’s reality is work. She takes less drugs when she works. She drinks less when she works. She agitates less when she works. If she goes down the drain, then I don’t know what the hell you got — maybe the best you’ll get is a wife in a hospital.”

Kijak said he was astonished when he first heard the way that the men were discussing a grown woman in her 40s, referring to her as a “sad, poor girl.”

“It’s so demeaning,” the director said. “We sit here from our perspective going, ‘What’s changed?’ There’s a temptation to look at it from the post-#MeToo movement. But there was just so much pervasive, systemic sexism then that she had to constantly fight against.”

‘The tenacity of a praying mantis’

Listening to Garland recounting her origin story, it’s difficult not to feel like her fate was sealed from birth. In the recordings unearthed for the film, she describes how her mother, Ethel Gumm, never wanted her to be born.

She “always took great delight in telling rooms full of people how difficult it was for her because I was not scheduled,” Garland said. “My mother did not want any more children. She did everything to get rid of me. She must have rolled down 19,000 flights of stairs, jumped off of tables, and for some reason I was a very stubborn child. I was not about to be shaken loose.”

Even at her lowest — like when she slipped into postpartum depression in 1952 — Garland never spent long wallowing. After taking a razor to her throat, she said she felt “a terrific feeling of guilt and awful shame ... because actually I didn’t want to die. I had a baby to live for. It was just that the pressure had been too much for me.”

Death, she insisted, was not at all what she wanted.

“When my number is up, I want a new one. I have no intention of checking out,” she promised the tape recorder.

What kept her going, she said, was her ability to laugh at herself — the fact that she never took herself seriously. “I have the tenacity of a praying mantis,” she said, “with a little black Irish witch involved.”

It’s that grit that Kijak is hoping audiences take away from “Sid & Judy.”

“Initially, I wasn’t that interested in Judy — the old gay world of her and Marilyn Monroe seemed like mothballs to me,” he said. “But when you sit down and listen to her and hear her perform, it cuts through all the bull and the pathologizing of her. She continued to be reborn so many times, and that alone is inspiring. She just pushed through all the tragedy.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.