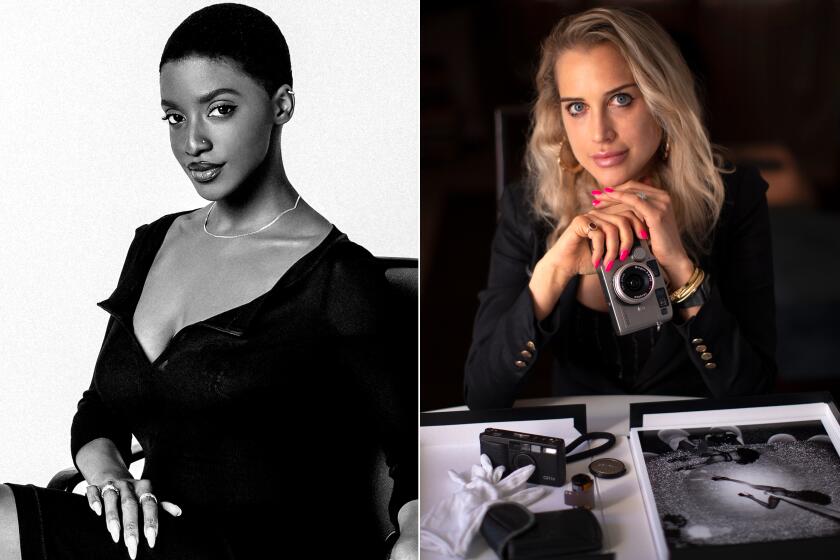

Aisha Harris’ ‘Wannabe’ offers stream-of-consciousness-style musings on the pop culture that shaped her

- Share via

On the Shelf

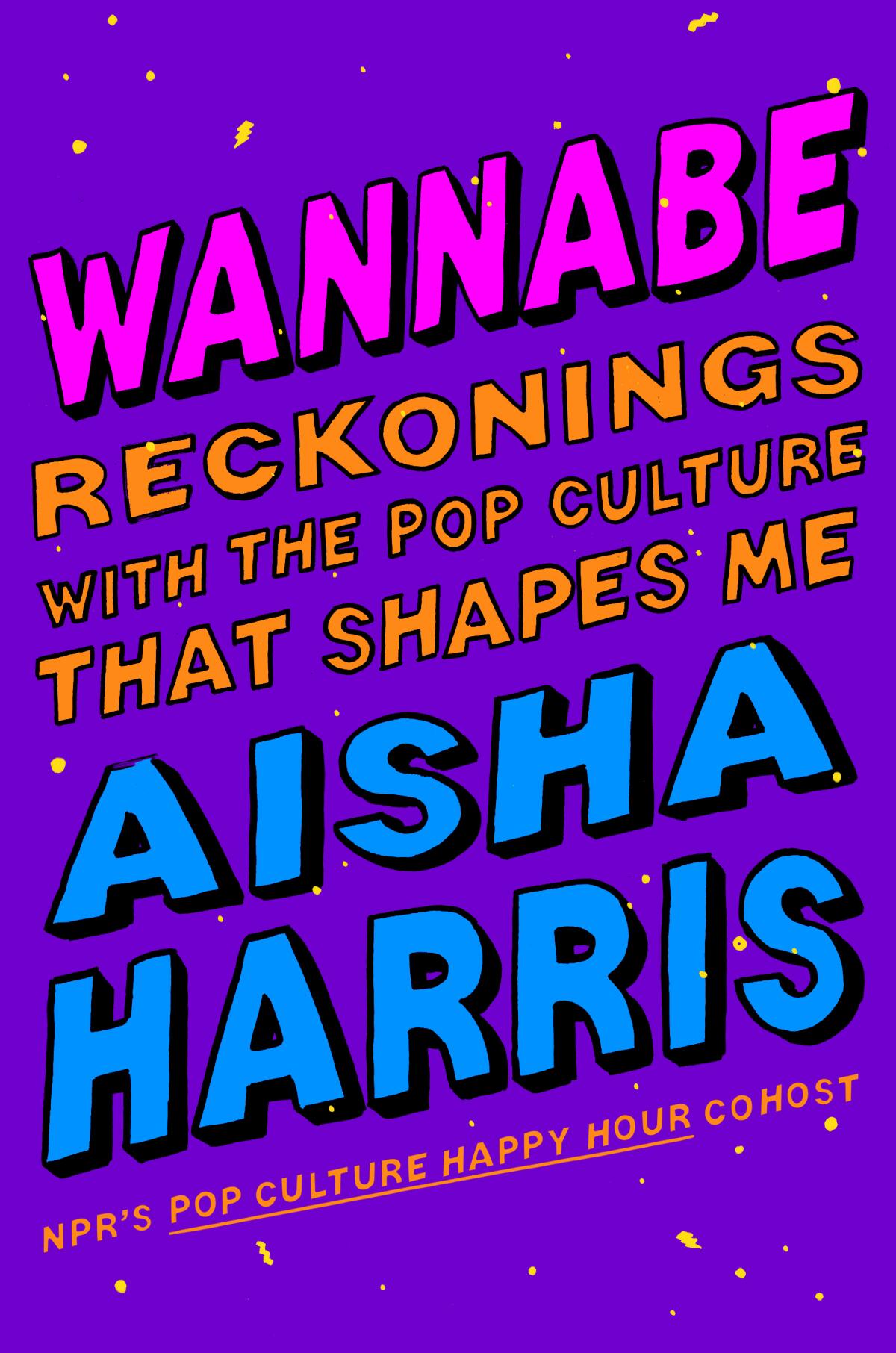

Wannabe: Reckonings with the Pop Culture That Shapes Me

By Aisha Harris

HarperOne: 288 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“It’s nearly impossible to escape this world untouched by pop culture: moviegoing, TV watching, music listening,” writes pop culture critic Aisha Harris in the introduction to her book, “Wannabe.” “It doesn’t all just happen to us — it helps shape us and informs how we move about the world, whether we’re conscious of it or not.”

The veteran writer and podcaster explores the myriad ways pop culture has affected her life and identity over nine essays in “Wannabe: Reckonings With the Pop Culture That Shapes Me,” stream-of-consciousness-style ramblings that touch on topics as disparate as the cult of celebrity and parasocial relationships, popular Black American names and the trope of the sidekick Black BFF, among other things.

Harris grew up in Hamden, Conn., a town just outside New Haven, before decamping to the Midwest for college at Northwestern University. There she studied theater and, later, film studies at NYU. “I thought for a little while that I might be on Broadway or be the next Disney Channel star because I could conceivably play a high schooler while I was still in college,” she said. “But I realized I didn’t really want to be a ‘starving artist’ and auditioning all the time, and I really loved film and TV and being able to write about it.”

Her pivot to journalism began with an internship at Slate magazine, where she blogged for the culture desk before being hired as a full-time writer and editor.

At Slate she had a few pieces go viral, including one titled “Santa Claus Should Not Be a White Man Anymore,” which was lambasted by Megyn Kelly and Fox News conservatives. She also served a stint as an arts and culture editor at the New York Times before landing at NPR as a co-host of the “Pop Culture Happy Hour.”

The Times caught up with Harris on the day of her book release to talk about everything from Scary Spice to “The Little Mermaid” and the state of pop culture today.

Your book is out today. How does it feel?

It’s surreal. I worked on the book for about two years during the pandemic and while I still had my full-time job at NPR, so it was quite an experience trying to juggle both of those things and stay creative. But it feels good and I’m just happy it’s out in the world.

What’s behind the title of the book, “Wannabe”?

So “Wannabe” is the title of one of the greatest pop songs of all time, by the Spice Girls. And the Spice Girls play a significant part in the book with my experience growing up right at their peak. I write about what Scary Spice meant to me as a Black girl who grew up with mostly white friends and white classmates and what it was like to look at Scary Spice as the one Black [girl] in that group. I also feel “wannabe” is a stand-in for the themes of the book when it comes to how we see ourselves in pop culture and how it reflects who we want to be or who we think we are.

Which of the essays is your favorite and which came to you the easiest?

None of them came to me easy [laughs]. They’re all various shades of anxiety-inducing. I’m one of those writers who actually hates the process of writing, who [only] likes the after-effects. But I think the one I like the most is probably the one about my name just because it’s the one I sat with the longest. It’s the first one I wrote. And I think that it kind of lays the foundation for the rest of the book and the many themes I’m trying to touch on, whether it’s the idea of self-mythologizing, of internalizing self-doubt or insecurities and also just going down many rabbit holes of various pop culture strains and ideas. It bounces around a lot from the ’90s and Another Bad Creation and “The Lion King” to Alex Haley’s “Roots” and back to “The Last Black Man in San Francisco.” It goes all over the place, but I think it really lets the audience know, “OK, this is where we’re going with the rest of the book. It’s gonna be a little bit of a ride.”

What pop culture moments would you say left the biggest impression or had the biggest impact on you?

I write about this in the book. The whole Disney renaissance had a huge effect on me just because it helped foster my love of musicals. These were the stories that I loved and they were one of my earliest obsessions where I would go back and rewatch those movies over and over. My mom would buy all of them on VHS, we’d get the soundtrack, put them in the car. We went to Disney World a couple of times when I was a kid, so I definitely think that was probably the biggest imprint on me.

And then the other one is probably when I discovered old movies and Turner Classic Movies, especially. I was and still am a huge fan of that. That was kind of a turning point that really helped guide and foster my love of movies and especially old movies and I think was a huge catalyst for me wanting to become a film critic/film scholar. I don’t know if you’re familiar with TCM, but before and after every movie they have the host come on and give a little bit of an intro putting into context the time period and whatnot. And I love those little anecdotes. I’m such a huge nerd about that kind of stuff. And I love to dig into archives and look at old reviews and old video clips.

Speaking about the Disney renaissance, I have to ask, what did you think about “The Little Mermaid”?

I wrote a review of it on NPR and people weren’t happy about it. Basically, the movie was more or less what I expected it to be. It wasn’t as bad as the “Aladdin” remake, but it was too long. Halle Bailey was fine, but overall, it was just very ‘mid’ and basically a copy and paste of the original, and it paled in comparison. I just want people to admit this. My review dropped before [the movie] came out, so there were a lot of people who were upset about it but hadn’t seen it yet. And I just want to know how many of those people still feel as though I was wrong.

Do you feel like you got to experience any kind of catharsis from this process of having to think about yourself in relation to pop culture?

Yeah, I feel like I got a lot off of my chest, in a way. Even just having this whole “Little Mermaid” remake come along, so much of what I write about in the book played out in that review coming out. And now whenever someone accuses me of not supporting Black art because I wrote a negative review of something a Black person made, I just want to be able to point them to my book, like, “Here you go. I have an entire chapter about this exact thing that you’re upset with me about. Read it and leave me alone.”

So much of popular culture and the lens through which it is reported on and depicted in media tends to come from a white gaze. To what extent have you had to examine the lens through which you’re consuming pop culture as a Black woman, especially one who has spent a lot of time in primarily white spaces?

When I first decided I wanted to be a critic, a lot of my focus was on representation and the idea of scarcity and not being able to see myself in film and TV as often as I’d like or in the ways that I would like. And as I’ve consumed more art and also as time has progressed, I’ve realized that, yeah, definitely the white gaze is the dominant gaze still in pop culture. But I also think today, there’s just so much art and film and TV and so many different streaming sites that you actually have to try a little bit harder to find the things that you like.

Earlier this year, Slate and NPR as a collaboration resurfaced our Black Film Canon, which originally published when I was still at Slate in 2016. The Black Film Canon is this canon of 50 films that were directed by Black filmmakers [including well-known films like] “Friday” or “Shaft,” but also films like “Losing Ground,” the Kathleen Collins film. We updated it this year because in the last seven years or so there has been a huge shift. When that list dropped in 2016, “Moonlight” was just a few months away from premiering, “Get Out” hadn’t premiered yet, and [in the time since] we have everything from “Black Panther” to “40-Year-Old Version.” And there are also some from the past that we hadn’t included.

And I saw that as a kind of an extension of the book, in many ways. While we are talking about issues of representation when it comes to Black people ... those are real things that exist. But we also don’t want to ignore or put aside things that already do exist just so we can bolster this argument that we need more. I think it’s important to acknowledge that there have always been Black filmmakers doing really interesting things. They might not have gotten as much attention as a Jordan Peele or a Barry Jenkins does today, but they’ve always existed. And it’s important to acknowledge that while also still fighting and arguing for better representation today.

In your second essay, you touch on how Black audiences tend to be hard on Black critics who speak unfavorably about Black art. What responsibility, if any, do you think Black culture critics and writers owe Black audiences?

I think we owe Black audiences the truth. For me as a Black critic, I think it’s important to not sugarcoat things and be honest about how I feel about Black art because I want to approach it just as I would any other piece of art. To me, that means taking it seriously even if I don’t particularly like it or think it’s good.

In that same essay, you speak about how there actually is not a lack of Black critics, people just aren’t looking hard enough for them. And as a fellow reporter, I have not personally seen a lot of Black critics, particularly in the film space. So to what extent is the difficulty of Black audiences in accepting negative critiques of our art due to the dearth of Black critics or lack of visibility perhaps for those that exist?

When I say that we have a lot of Black critics, I’m not saying that they’re necessarily in all of the major publications, but we are there. There’s a few of us at NPR. There are some at the Ringer. There’s some at the New York Times, they exist at the Washington Post. There’s Black Girl Nerds. One of my friends, Odie Henderson, is newly a film critic at the Boston Globe.

I acknowledge that in my bubble I know who the Black critics are. So, yes, for people who are strictly film critics, there are not as many. So I do think it does say something about just how hard it is to turn the tide of expectations and assumptions. Because the legacy of access and how [few] Black people have been employed at these places in the past is not going to be [resolved] just hiring a few people in a short span of a few years. It takes a lot more to do that. And I think that is on those publications and those media companies to really platform those writers in a way that doesn’t feel exploitative or like the year 2020 when everyone’s jumping to say, “Oh, hey, we have Black people here! We’ve hired a bunch of Black people.” I mean, how many of those Black people are still employed? I don’t know. But I do think there’s a give-and-take. I think it’s partially on the audience, for those who really care about those sorts of things, to seek them out.

With the constant stream of content, news updates and publicity stunts today, do you think pop culture still has the same power to shape young minds as the things that we grew up with?

I think perhaps even more so, just because studios and celebrities know how to wield social media for their benefit. There’s been plenty of studies showing that social media is ruining young people’s minds. But I really do think that it’s become even more a part of a wider range of people’s identities because now you can participate in your standom with other people virtually. And there are so many ways to express that, whether it’s going to a theme park based entirely around your childhood or Comic-Con. Now there’s ’90s conferences where all the stars from when I was young like “Kenan and Kel,” “All That,” they have conferences now where people get to relive their ’90s dreams. So I definitely think it’s become even easier for people to indulge in their fandom that it ever was before.

Do you have any predictions for the immediate future of pop culture? Are we recycling trends or are we in uncharted territory thanks to social media and the internet?

It’s the Wild Wild West right now. Everything from the music industry to TV to the movie industry is in a weird place, with influx from the idea of AI to the WGA strike to streaming and whatever the heck is going on over there. Trying to get people into theaters and TikTok becoming a place where songs become hits. I just think we’re in a weird place and I don’t know when the dust will settle. But I think when it settles, we are going to see some shifts in terms of power dynamics and who wields that power. And I don’t necessarily think that it’s going to be the corporations, per se. I mean, yes, they have the money and they’re not losing that money anytime soon. But I do think audiences might get fatigued and fed up with feeling as though they are being taken for granted, especially as more and more things disappear from streaming devices. I think that things are shifting and things just keep getting weirder and more complicated.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.