Why Agatha Christie’s mousetraps still beguile us, even if the films aren’t always killer

- Share via

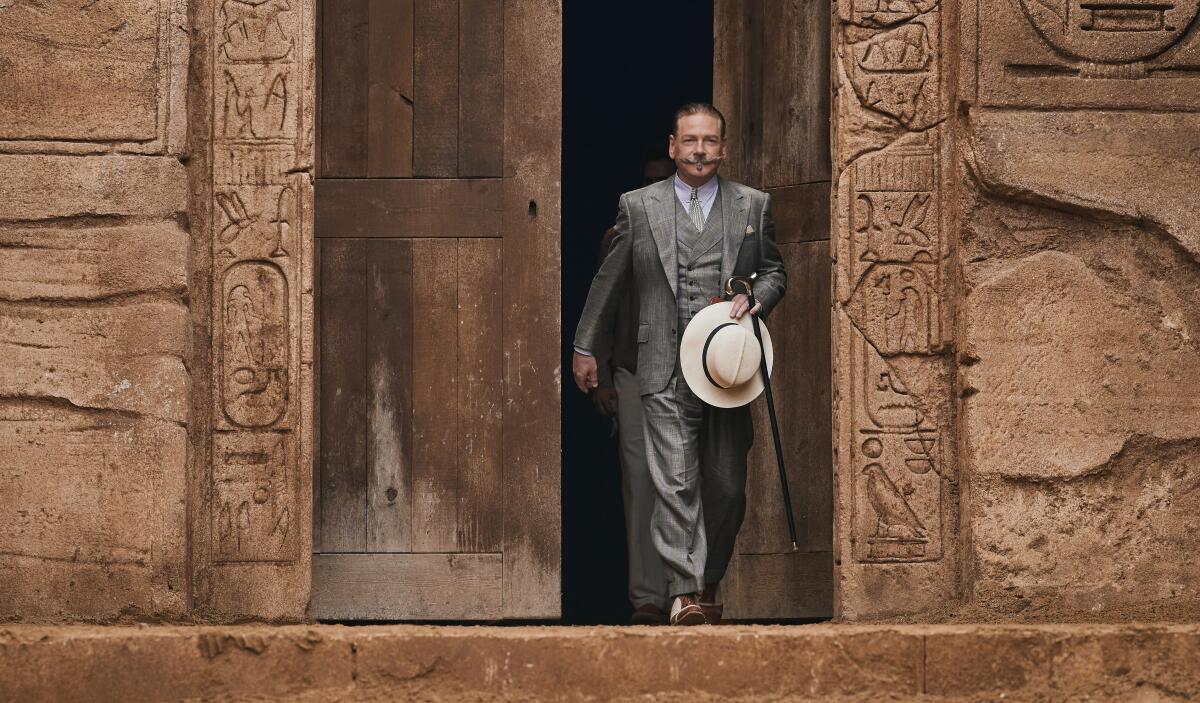

After two relatively faithful adaptations of Agatha Christie’s “Murder on the Orient Express” and “Death on the Nile,” director-star Kenneth Branagh goes wildly off-book with “A Haunting in Venice,” which arrives in theaters Friday. Once again playing Christie’s most famous character, the Belgian ex-police inspector turned private detective Hercule Poirot, Branagh shoots largely on location, specifically in a moldering palazzo said to be haunted by orphans left to die during a cholera outbreak. Coaxed out of retirement by his friend, the crime novelist Ariadne Oliver (Tina Fey), Poirot sets out to debunk a famed medium (Michelle Yeoh) and winds up having something of an existential crisis along the way.

Times culture critic Mary McNamara and film critic Justin Chang, both self-described Christie nerds, have more than a few things to say about the results.

MARY McNAMARA: The biggest mystery of “A Haunting in Venice” is, of course, why it bothers to claim to be based on the 1969 Christie novel “Hallowe’en Party.” Both take place during Halloween, both include Poirot, Ariadne Oliver and many references to apples (of which Mrs. Oliver — here “Miss” — is notoriously fond), and both share a few character names as well as a brief reference to a previous case.

Other than that, though, niente.

There is not only no Christie novel called “A Haunting in Venice,” there is no Christie novel set in Venice. Poirot preferred to vacation on the French Riviera and British seaside and the one time he did officially attempt to retire (“The Murder of Roger Ackroyd”), it was to grow vegetable marrows in a British village.

In “Hallowe’en Party,” a 13-year-old girl is murdered at a village fete after claiming that she once witnessed a murder. Other deaths ensue before Poirot solves the crimes, and though the novel has one of Christie’s more fantastic endings, no ghosts or ghoulies are involved at any point. Which is a long-winded way of saying anyone looking for a cinematic adaptation that is even vaguely recognizable as “Hallowe’en Party” would be better served by watching the “Agatha Christie’s Poirot” British TV version, starring the great David Suchet.

But having seen the decidedly spooky trailer and the two previous films, I knew this going in. From the moment Poirot set foot on the Orient Express and certainly as he set sail down the Nile, Branagh and screenwriter Michael Green have been deeply committed to making the world’s second most adapted literary detective another man entirely.

Where Christie’s Poirot was occasionally irritated (by bad food, asymmetrical mantel decor and his own miscalculations), Branagh’s Poirot is perpetually in a state of mourning. Still brilliantly observant, obsessively neat and elaborately mustachioed, his version bears psychic wounds from his service in World War I and the subsequent death of his true love Katherine. (It was she who suggested he grow a mustache to cover the scars he received in the trenches.)

When this outrageous and, frankly, heretical love-and-mustache backstory was introduced in “Death on the Nile,” I almost threw my popcorn at the screen. Mercifully, the rest of the film was so bad for so many reasons, I quickly moved on to groaning about other things.

But I am a sucker for any movie shot in Venice. Also I was curious see how far Green and Branagh would go — would some dear departed Poirot child appear? Would he find love with Mrs., er, Miss Oliver? Would I run screaming from the theater, if not in fright then in fury?

Mais non, mon ami Chang. (Sorry.) Having accepted this haunted version of Poirot, and the fact that it would bear no resemblance to any Christie story I have ever read, I actually quite liked “A Haunting in Venice.” It was spectacularly spooky and, though I guessed the main plot twist early on, quite entertaining. What did you think, Justin?

JUSTIN CHANG: I’m with you, Mary. While I don’t love that title — I’d have much preferred something like “Venice the Menace” or “Venice, Anyone?” or “Gondola With the Wind” or “Catch Me If You Canal” — there’s only so much one can protest about a movie set and shot in the world’s most jaw-droppingly beautiful city, especially when it makes room for “The Grudge”-style jump scares and a screaming, gyrating, temporarily demon-possessed Michelle Yeoh. Oh, and speaking of heresy: While Christie certainly wrote her share of gruesome murders, I can’t recall any offhand in which the victim falls several stories and gets impaled on a sharp spike. What was the inspiration for this, Michael Bay’s “The Rock”? (I’m not complaining, just wondering.)

I’ll have more to say in my review of “A Haunting in Venice,” but as someone who also disliked the earlier Branagh–Poirot movies, I too was more charmed than irked by Green’s many departures from the source material this time around.

I’m generally a defender of irreverent, flagrantly unfaithful adaptations, especially when the book in question isn’t memorable to begin with. Unlike “Murder on the Orient Express” and “Death on the Nile,” both frequently and capably filmed before, “Hallowe’en Party” isn’t a great or even good mystery. I remember finding it one of the more tedious and thinly plotted of the 80 or so Christies I plowed through decades ago, though since I know you’re a fan, Mary, I’m open to giving it another look.

Branagh remains marvelous as Christie’s most famous sleuth, though like you, Mary, I’ve expressed my share of frustration with these movies’ insistence on giving us Emo Poirot, Lovelorn Poirot and Existentially Tormented War Veteran Poirot. (There’s mercifully less of that in “A Haunting in Venice,” though I can’t say that Atheist Poirot, bent on using reason to take down Yeoh’s faith-peddling medium, is any less of a cliché.) The attempt to turn Poirot into a plausible romantic lead, or at least to suggest a backstory awash in thwarted passion, has always slightly felt designed to flatter Branagh’s ego — and also to deepen and humanize a character often reduced to the sum of his attributes and mannerisms: the mustache, the egg-shaped head, the “little gray cells of the mind.”

Christie famously grew tired of Poirot herself, and often resented him for being more of a reader favorite than her other great sleuth, Miss Marple. There’s a reason (four-decade-old spoiler alert!) she killed off Poirot in “Curtain” but ensured that Miss Marple survived her last case, “Sleeping Murder.” (Christie even subjected herself and Poirot to some sly self-parody by giving Mrs. Oliver an annoyingly popular sleuth of her own, a Finn by the name of Sven Hjerson.) But I’ll confess that Poirot is, by several crime-scene chalk outlines, my favorite fictional detective, and while I’m not in love with Branagh’s big-screen revival, I can’t help but look forward to the next one.

Mary, what are some of your favorite Christie novels, or, if that’s too hard to narrow down, which ones would you like to see Branagh (or someone else) adapt next?

McNAMARA: I do hope Green and Branagh give us another, and I nominate “Mrs. McGinty’s Dead,” if only so Fey can return as Miss Oliver (the original being an obvious avatar for Christie), and have a conniption over a young playwright’s attempt to make Sven younger, less eccentric and more magnetic to women. It’s highly meta and precisely what Christie did when similar changes to Poirot were suggested for the first stage adaptation of “The Murder of Roger Ackroyd.” Though, to be fair, neither Green nor Branagh appear interested in winking at the audience.

I confess it was more than a little jarring to see my beloved scatterbrained Mrs. Oliver turned into Fey’s stylish, fast-talking writer on the make. But the steely-eyed, tart-tongued version was a natural match for mournful Poirot, and Fey provided more than a few delightful moments.

It’s impossible for me to name a favorite Christie novel, but thinking cinematically, “Elephants Can Remember” (also with Mrs. Oliver) could work. “Evil Under the Sun” has been popular with Hollywood; “Hercule Poirot’s Christmas” would be a great holiday film; and I know you are a big fan of “Five Little Pigs,” Justin.

CHANG: While there has already been a Suchet-starring TV adaptation, I would love to see a big-screen version of “Five Little Pigs,” of which the late crime novelist and Christie scholar Robert Barnard once wrote, “The present writer would be willing to chance his arm and say that this is the best Christie of all.” I don’t know if I’d chance my arm, but I know the novel is an absolute masterpiece — not only one of the most beautifully plotted of Poirot whodunits, but also by no small margin the most beautifully written.

“Five Little Pigs” is an unusually melancholy story, partly because the mystery is set in the past (the book was published in the U.S. under the title “Murder in Retrospect”), and partly because most of the suspects — the “five little pigs” of the title — are members of a family that has clearly never made peace with this tragedy. Poirot’s investigation, undertaken through a fog of unreliable witness accounts, brings all manner of forgotten memories and half-buried resentments to the surface. The skill of Christie‘s sleight-of-hand is matched by a rare depth of characterization and a sense of tragic futility that lingers in a way few of her mysteries do.

Branagh would be great starring in it (and Emo Poirot would actually be welcome in this instance), though someone else should direct. Weirdly, Florian Zeller, with his gift for dramas about memory and family tragedy (“The Father,” “The Son”), comes to mind.

McNAMARA: I think I’ll stick with “Mrs. McGinty’s Dead.” It has a grisly if mundane murder that broadens into some very creepy plot twists (famous child murderers!), with a side of the always-popular media bashing. It also forces Poirot to stay in a very uncomfortable guest house, good for laughs, which is run by the chronically overwhelmed Maureen Summerhayes, who could easily be made into an age-appropriate widow/potential love interest. And considering Green and Branagh’s penchant for dramatic atmosphere, the story would work just as well in the Scottish Highlands, Ireland’s County Mayo or some other place of sweeping vistas and towering crags. (Copyright mine.)

But honestly, given “Haunting’s” complete disregard for everything except the most essential original content, there’s no telling. They could choose to do what so many fans longed for and have Poirot finally meet Miss Marple. Which might be nice; she could just twinkle at him over the fluffy jumper she was knitting and tell him how he reminded her of that young actor she once saw in “Henry V” who, scandalously, left his first wife for a lovely actress but eventually pulled himself together.

What would you think of a throwdown with Miss Marple? Or would you prefer Poirot bump into the mysterious Mr. Quin?

CHANG: So long as they don’t have him encounter Tommy and Tuppence Beresford, who, all due respect, have always bored me to tears. Otherwise, I’ll be just fine with whatever they cook up next. Like you, Mary, I didn’t mind Fey’s tart-tongued take on Mrs. Oliver, however textually inaccurate she may be. As it happens, I went into “A Haunting in Venice” completely cold and, as a big Fey fan, was delighted to see her pop up in such a prominent role.

That said, yes, I would be all for “Poirot v Marple: Dawn of Justice,” provided they find the right actor to play Miss Marple. Maybe not Emma Thompson (bad joke, I know, but your reference to “Henry V” and first wives raises fascinating possibilities). It’s not an easy task, given all the great Miss Marples played by Margaret Rutherford, Angela Lansbury, Joan Hickson and Geraldine McEwan, though I’m of the general opinion that one can never go wrong with Imelda Staunton. The question, of course, is who would solve the mystery first, Poirot or Marple? Perhaps they experience their “Eureka!” moments simultaneously, and then take turns explaining it to the rest of us.

In the first of a new series reviewing Hollywood book adaptations, Bonnie Johnson asks if Kenneth Branagh’s latest Agatha Christie reboot is necessary.

McNAMARA: I love Poirot, but Miss Marple, who got far fewer novels and stories, always seemed to me the more significant literary creation.

Poirot, like Sherlock Holmes and Edgar Allan Poe’s C. Auguste Dupin before him, was a professional detective. His accent and dandified appearance may have lulled people into telling him things they would not disclose to police, but Jane Marple was (and still is, alas) society’s definition of non-threatening: a highly genteel elderly lady, often misidentified as a gossip. But the understanding of human nature she cultivated in a lifetime of being overlooked is precisely what allows her to see what others could not.

She also had, in her own words, a mind “like a Victorian sink” — she always suspected the worst and was often proven correct. TV’s “House” may have been based on Holmes but his credo, “Everybody lies,” is pure Marple. Christie may not have invented the non-professional detective, but Miss Marple remains a template for the amateur sleuth.

You could argue that Dorothy L. Sayers, writing at the same time as early Christie, also contributed to the sub-genre with her creation Lord Peter Wimsey, who often went incognito as a “silly ass.” Sayers had her own insightful elderly “spinster,” Katherine Climpson, employed by Wimsey exactly because no one thought it odd that an older woman would be nosy. And in the character of Harriet Vane, Sayers also conjured a mystery writer much like herself, before Mrs. Oliver appeared, and in a far more directly romantic context.

Sayers and others may have been better novelists, but Christie’s palette was uniquely vast and surprisingly fearless — from deeply domestic village murders to international conspiracies, often designed to remind us that the threat of fascism is always with us. Over and over, Christie persuaded us that no matter how clever a murderer was, no matter how unlikely the truth turned out to be, justice would eventually prevail. Which is probably why some of us read her religiously.

Sorry (she said, stepping off her soapbox), this has wandered quite a bit from “A Haunting in Venice.” Though maybe not: Fey’s Miss Oliver had a neat little speech about why mystery novels remain popular that I quietly applauded. Why are you such a devout fan of the genre, Justin?

CHANG: Mary, your point about justice prevailing reminds me of the work of P.D. James, one of my favorite mystery novelists (and novelists period). She wrote extensively about the pleasures and satisfactions of the detective story, which in her mind are predicated on a problem that is “solved, not by luck or divine intervention, but by human ingenuity, human intelligence and human courage. It confirms our hope that, despite some evidence to the contrary, we live in a beneficent and moral universe in which problems can be solved by rational means and peace and order restored from communal or personal disruption and chaos.”

If that sounds cozily reassuring, James nonetheless knew that the restoration of order is not always inevitable, and she turned that into a major source of tension in her work. In the complexity of her characterizations, the psychological acuity of her writing, she balanced our desire for order with a deep understanding of how cruel and unjust the world can be. Unsurprisingly, James didn’t think much of Christie and often resented being compared to her. She disdained Christie for reducing murder to a parlor trick, with her narrative formulas and cipher-like characters.

I know what she means, really I do. I love the literary heft and somber realism of James’ work. But I approach Christie’s work in a very different spirit, and if I’m honest, Mary, I do love a good parlor trick. I love being hoodwinked, led up the garden path, dazzled by red herrings and then awed into submission by an ingenious finale. Is this all the detective story is good for? Of course not. But Christie has given me too many hours and years of pleasure for me to complain.

The durability of her work is obvious, given the enduring appeal of the murder-mystery template that she helped pioneer and innovate. Christie lives on not only in the myriad screen adaptations of her work, but also in films as varied as Quentin Tarantino’s “The Hateful Eight” and Rian Johnson’s “Knives Out” movies (which reminds me, I need to catch up with “Poker Face”). She lives on in “Only Murders in the Building” and “Magpie Murders” and countless other examples that you can surely school me on, Mary, your little gray cells being way sharper than mine.

And Christie lives on, yes, in “A Haunting in Venice,” and in Branagh’s series of adaptations that — for all their flaws, and there are many — still have us dying to see what happens next.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.