Two ‘dance partners’ find their way to the black-and-white world of ‘El Conde’

- Share via

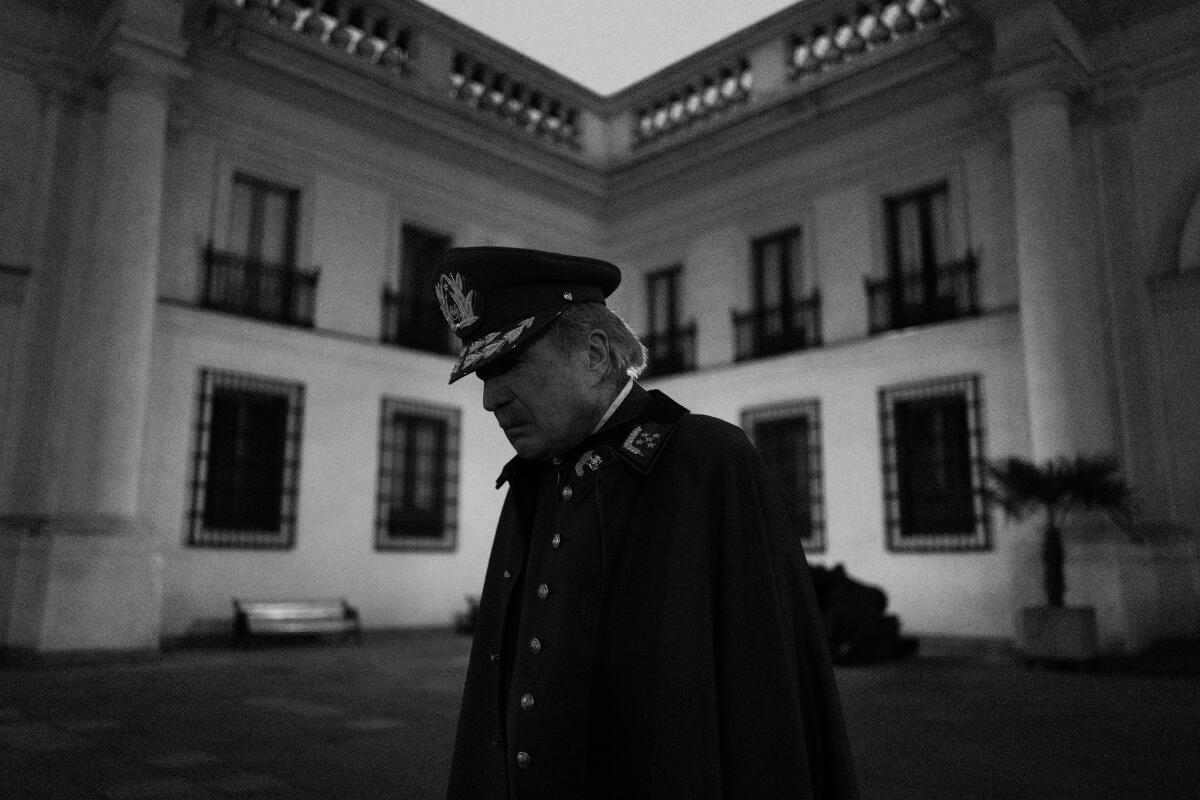

Part gothic horror fable and part political parable, director Pablo Larraín’s new “El Conde” is a story told with imagination, anger and mournfulness. Playfully, the film suggests that Augusto Pinochet — who 50 years ago led a military coup that made him the brutal, feared leader of Chile — was, in fact, a vampire. Having faked his death, the 250-year-old creature now lives out his days in isolation as his aging children squabble over the hidden spoils of his years as a dictator.

Larraín describes his film’s Pinochet as “an absurd superhero of evil” and says he knew early on that he wanted the film to be shot in black-and-white.

“It’s a more theatrical image,” Larraín says. “It invites a different perception of reality.”

For that, he turned to veteran cinematographer Ed Lachman, who, for Larraín, crafts indelible images of Pinochet in his ornate military uniform and ceremonial cape, etched in vivid detail with a startling crispness. The film is somehow sparse and flamboyant at the same time; viewers may feel conflicting impulses of being charmed and repulsed.

The film premiered at the Venice and Telluride film festivals before having a limited theatrical release. It’s now streaming on Netflix.

The Chilean-born Larraín is best known for his biopics “Jackie,” starring Natalie Portman as Jacqueline Kennedy, and “Spencer,” starring Kristen Stewart as Princess Diana. Earlier films such as “Post Mortem” and “No” (the latter nominated for the Academy Award for foreign language film) often dealt explicitly with the cultural fallout of the Pinochet regime.

When pressed, Lachman can describe his personal style of shooting, though he’s quick to stress that sometimes that’s not the job.

“It’s like your fingerprint — I know there are things that are important to me,” Lachman says. “I have a certain predilection toward certain framing, the way I use color, the way light is. I don’t like you to feel movie lights. I like you to feel like the light is emanating from the space, the relationship of light to the environment.

“But I hope that my approach is different in each film,” he continues. “And that’s what excites me. I don’t want to impose a style. That’s not my interest. My interest is to find what the visual grammar is of that story, in what makes those images unique to that story.”

Lachman and Larraín have known each other for several years, but this is the first feature they‘ve worked on together.

“Ed can create a very particular visual poetry, but he never loses the focus on the narrative,” Larraín says. “That is very important because sometimes you see beautifully photographed films that don’t have a strong and powerful narrative. It was often very moving to see the images he was creating.”

Lachman, 75, calls himself “kind of semi-retired,” but he still has a full work schedule. He broke his hip near the end of production on “El Conde” and missed a few days of shooting. His injury caused him to be unable to shoot his longtime collaborator Todd Haynes’ latest film, “May December.”

Born in New Jersey, Lachman literally grew up around the movies: His father owned a movie theater and distributed projector parts. “As a kid, I used to put the popcorn in the bags,” Lachman remembers, “and that’s why I can’t go near popcorn.”

Yet it wasn’t until he took a film appreciation course while at Harvard, thinking it would be easy to pass, that a real passion for movies and storytelling ignited in him. Already a painter and photographer, Lachman began making films of his own — and eventually other people asked him to shoot for them as well.

An early breakout was Susan Seidelman’s 1985 NYC comedy “Desperately Seeking Susan,” co-starring Rosanna Arquette and Madonna. Lachman’s long list of credits includes David Byrne’s “True Stories,” Sofia Coppola’s “The Virgin Suicides,” Steven Soderbergh’s “Erin Brockovich” and Robert Altman’s “A Prairie Home Companion.” His ongoing collaboration with Haynes has yielded him two Oscar nominations, for “Far From Heaven” and “Carol.”

“It’s like I’m plugging into their world, a world that I’m not part of,” said Lachman, who sees himself very much as a collaborator, . “It’s kind of an adventure. I like to find out why people make films the way they do. The language of how you tell the story is as important as what the story is.”

In conceiving of the look of the film, Larraín and Lachman talked about landmark silent horror films like F.W. Murnau’s 1922 “Nosferatu” and Carl Theodor Dreyer’s 1932 “Vamypr,” as well as work by photographers from different eras including Sergio Larraín (no relation), Fan Ho and Maura Sullivan.

Knowing that Larraín wanted to shoot in black-and-white but also have the mobility of a light camera that could be used on a crane (there are flying scenes), Lachman reached out to his contacts in Germany at the camera company ARRI and discovered that they had been working on a digital camera with a monochromatic chip that was not yet publicly available, but which they were able to provide to him.

Building on his vision, Lachman used lenses retrofitted with vintage glass from the 1930s and modified to work on the secret ARRI camera. This unique combination of equipment was then used with Lachman’s own patented EL Zone System, which employsconcepts utilized by photographer Ansel Adams to control different exposure values throughout an image. The dazzling textures of the images in “El Conde” come from Lachman’s unique combination of technology and artistry.

“I was surprised,” says Larraín. “I didn’t know he was going to go that far with that specificity.”

As engaged as Lachman is in talking about the technical aspects of how the look of the film was achieved, he is equally passionate in exploring the scenario’s thematic ideas.

“It’s not a traditional romantic perception of a vampire movie,” he offers. “It’s literally and metaphorically the idea of what a vampire is. Pinochet died wealthy and free of his crimes, but the pain is eternal for the people. The idea of evil is it’s always feeding on itself. So it’s a much better way to think about a vampire. History repeats itself, so even if we can’t change, at least we can understand why this happens.”

Unusually, director Larraín himself operated the camera on “El Conde” for the entire shoot.

“It helps me to be closer to the actors,” says Larraín. “I’m too anxious to be seated at a monitor. Even when I’m not operating, I’m standing and working and walking. I can’t just see the world created in front of me. I have to be right there. You’re part of the process.”

Lachman recalls, “He wanted to operate the camera, and it was fine with me. The wonderful thing about operating is you are the first audience and the actor almost responds to you as the first person to experience it. And he is a wonderful operator. I understand why directors like that. It’s like a painter who doesn’t want somebody else to hold their paintbrush.”

On operating specifically for Lachman (no slouch), Larraín says, “It was a beautiful collaboration. And I learned a lot , being the cameraman for him.”

For Lachman, that sense of shared experience is key.

“I think why a lot of directors like to work with me is I come with a lot of ideas,” says Lachman. “I’m not like a cinematographer that just shows up, tell me what to do. I do have an opinion about the way I think you can do something. If they have a vision, then I can plug into that vision and help them realize what it is they want to do. And if it’s something that I don’t agree with or don’t think is the best, I found the best way to approach that is to say, ‘What’s important to you? Why do you want to do it that way?’ And even if I don’t agree all the time, what happens between us is what makes it interesting.”

He arrives at the perfect comparison. “They say it’s a marriage, but I say it’s a dance partner,” he adds. “It’s how you complement each other in how you make your steps.”

Following “El Conde,” Lachman and Larraín will move on to a project about legendary opera singer Maria Callas starring Angelina Jolie. Though both are reluctant to discuss any details on the look, you can expect them to be in lockstep.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.