An experimental prophet returns from his wilderness with a new film for children

- Share via

Godfrey Reggio is 83 years old. He smokes a pack of cigarettes a day. He’s not planning on quitting — in fact, he believes his habit kept him alive during the COVID pandemic.

“It’s actually good for me,” he declares over Zoom from his home base in Santa Fe, N.M. “When I got really ill, I went to a pulmonologist and said, ‘I really can’t stop smoking.’ He said, ‘Well, it’s helping to save your life. You’ve been smoking for 60 years — it’s protecting you from the virus.’”

Wearing tinted glasses and a cozy beanie, his flowing white beard extending below the edge of the frame, Reggio has a glint in his eye as he tells this story, although he adds, “I’m not recommending it, please.” But there’s no question that the smoke around him enhances the aura of this filmmaker-philosopher, who, for 40 years, has made visionary movies about humanity’s uneasy relationship with technology. To those who adore his mind-expanding, non-narrative cinema, Reggio is treated like a guru — and we nearly lost him.

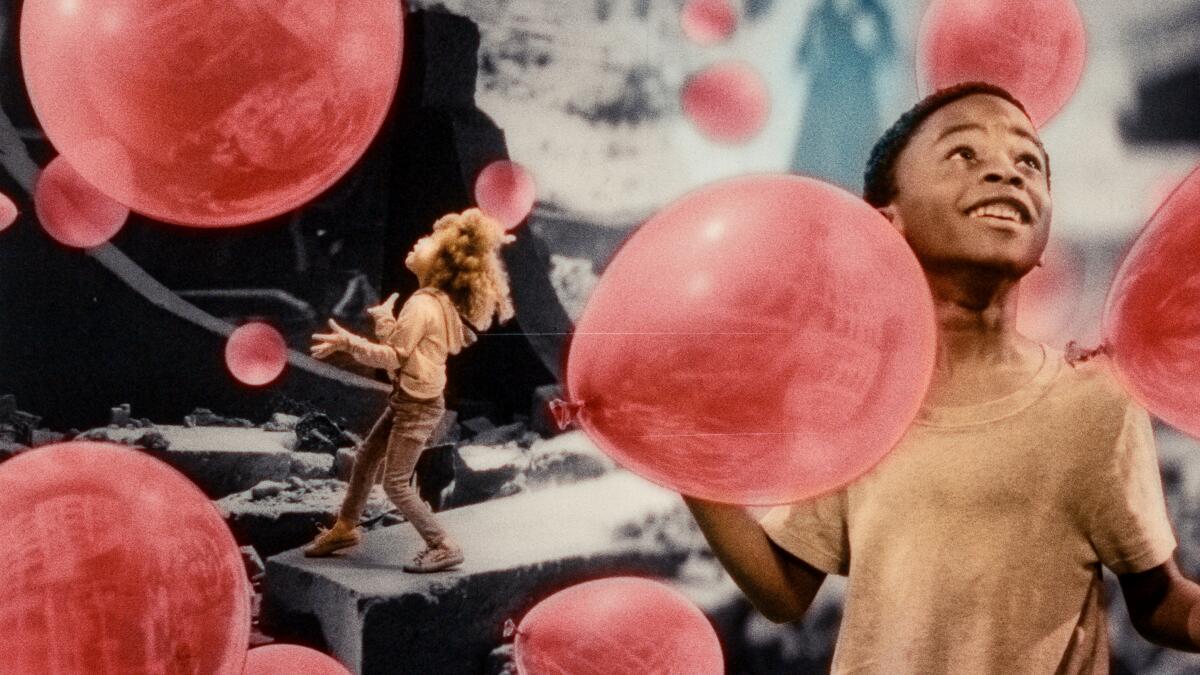

It’s early October as he discusses his latest project, his first film in a decade, which opens at Fairfax’s Brain Dead Studios on Friday. Running 52 minutes, “Once Within a Time” is the closest Reggio has come to anything resembling a traditional story. The man behind the “Qatsi” trilogy — 1982’s first installment, “Koyaanisqatsi,” remains a pillar of wordless filmmaking — has at last tried his hand at crafting characters and a wisp of plot, teaming up with frequent collaborator (and now co-director) Jon Kane to pair green-screened actors with digital effects and miniatures.

Part fairy tale, part salute to silent cinema and part surreal nightmare (there’s even a Mike Tyson cameo),“Once Within a Time,” like all of Reggio’s work, is about “life out of balance,” which is what koyaanisqatsi means in Hopi. The occasionally apocalyptic film features images of towering cellphones held by disembodied hands, children’s faces being digitally scanned and a massive Trojan horse consisting of electronic parts.

As is always the case, “Once Within a Time” took years for Reggio to complete, the writer-director reshaping the project as it went along. But a few months before wrapping, he came down with COVID. The prognosis was dire.

“I didn’t think he was going to survive,” Kane admits in a separate interview. “He is not really into medicine, but he called me one day and he couldn’t breathe. I was like, ‘Godfrey, you need to go to my doctor immediately. I’m going to make a phone call and tell them that a national treasure is on the brink.’ ”

Spend any time with the garrulous Reggio and he’ll invoke wisdom from Nietzsche, Plato, Baudelaire. He tends to speak in elaborate, meandering musings, although he’s slightly more direct when the conversation moves to his health scare.

“I was ready to die,” he says. “But I wanted to hang around for the project, so I got better.”

That attitude might seem cheeky, but Reggio has become accustomed to the nearness of death. “When I was 4 years old, I had 106-degree fever,” he recalls. “When I was 9 years old, I had pneumonia of the kidneys. I’ve had six automobile accidents — I slit my tongue in half in one. I’ve had a lot of occasions for death. I’ve been with people who’ve been shot right in my arms. I’m sure it affects me, but I don’t think about it. I mean, compared to the madness of what’s going on with Black people and the madness of Kosovo and Ukraine, it’s a little pain in a big cauldron of pain everywhere.”

When conceiving “Once Within a Time,” Reggio wanted to make a film for children. “Kids are not of the future, they are our future,” he explains. “The demographics, they’re over half the planet already.”

But where other directors will speak of their creative evolution over years, Reggio believes that what he’s exploring isn’t so different from “Koyaanisqatsi,” with its stunning juxtaposition of gorgeous views of the natural world and despairing sights of overcrowded metropolises, all scored by his longtime friend Philip Glass. (The new film is too.) Seeing “Koyaanisqatsi” in college inspired Kane to abandon pre-law. And it radicalized an aspiring director named Steven Soderbergh, who has executive-produced several of Reggio’s recent pictures.

“I don’t think anybody was quite prepared for the experience that it provided,” Soderbergh says of “Koyaanisqatsi” in a separate interview. “Back then, our sense of how nature and technology were interacting was not as deep as it is now. It seemed to articulate a feeling that was in the air, in a nonverbal way, that was incredibly powerful. As far as the general public goes, he’s probably one of the most influential unknown visual artists of the last 40 years.”

Darren Aronofsky’s ‘Postcard From Earth’ brings pieces of the planet to Vegas’ newest venue. It’s gorgeous — in a Disney amusement kind of way,

Not bad, considering that, as Reggio puts it, “not a person who worked on it thought anyone would see it. One person believed in it, and it was me. And it became a cult classic. It was ripped off by everybody, including ‘Grand Theft Auto’ and Madonna.”

Indeed, the film’s marriage of sound and vision helped define the burgeoning MTV aesthetic (co-director Kane got his professional start at the channel during its infancy), its impact bleeding into commercials and nature documentaries. Reggio is pleased with the many homages to his opus. “Everything gets consumed,” he says. “It was designed to be consumed by the beast.”

For “Once Within a Time,” Reggio met daily with Kane and his team at their Brooklyn studio, describing the project in abstract terms. It was up to Kane, who has worked with Reggio since the final chapter in the Qatsi trilogy, 2002’s “Naqoyqatsi,” to translate those loose concepts into concrete images.

“It’s a collective mind-dump,” says Kane about those morning meetings. “He gives a whole sermon: ‘Act Three is called “House on Fire” — everything’s burning!’ He’ll go on and on about the Bible connections, but in my mind it’s like, We gotta learn how to render fire. We shot 400 days on this film, if you count all the testing days.”

Reggio’s fans know his near-mythic backstory: how he left home at age 14, how he joined a Roman Catholic religious order soon after, then became a teacher and later started an organization that tended to juvenile street gangs, committed to assisting the poor and the marginalized. Less well-documented is his personal life. Reggio has such fondness for children, convinced they can create a better tomorrow, but does he have any of his own? “I have no children that I’m aware of from my own seed,” he replies cryptically. “I have three adopted daughters, as it were, from their mothers. And I have a lot of barrio kids that call me daddy. So I have a lot of kids in that way. I’m a lucky guy.”

He is tickled that so many younger viewers are catching up with his work online, although he’s adjusting to the encounters he has with them in public. “They want to come touch my beard,” he says, amused. “I don’t have teeth — my eyes are bad, my ears aren’t great. I look the way I am, but they want to take their picture with me. It’s like I’m being canonized before I die. It’s a weird experience, but you take it in stride. We all have big egos. Mine’s huge. But no vanity of ego. Just accept it and move on. I got plenty other things to do.”

The news of Reggio’s near-death experience infuses “Once Within a Time” with an extra layer of poignancy, his grappling with humanity’s uncertain future taking on even greater stakes. “[The movie] feels like a summation of sorts,” Soderbergh suggests. “Or at least a coda that incorporates everything he’s ever done and everything he’s interested in. He is a very hopeful person — he’s the opposite of a dark personality. He is pro-humanity while being very critical of some of our choices.”

But because his movies can often be mysterious and elliptical, Reggio provokes skepticism in some. Evaluating Reggio’s ravishing, image-driven 2013 picture “Visitors,” Christian Science Monitor critic Peter Rainer wrote, in a positive review, “I’ve never been able to figure out if Reggio is an artist or a con artist.” Reggio is delighted to clear up any confusion.

“Oh, a con artist,” he replies without hesitation. “I speak, as Nietzsche says, as if I know what I’m talking about.” Insisting he’s still a child himself, Reggio has spent his life happily faking it until he makes it. “Begin, and the work will show you how,” he offers.

Kane marvels at how much Reggio comes to life when working. “He wilts when there’s no energy around,” he says. “He knows what he needs, and really what he needs is to be in the process of making the movie. This is his health plan — he doesn’t feel well when he is not smoking and drinking whiskey all day.”

If Reggio is a con artist, he seems to be outsmarting mortality itself.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.