Joseph Shabalala, founder of famed vocal group Ladysmith Black Mambazo, dies at 78

- Share via

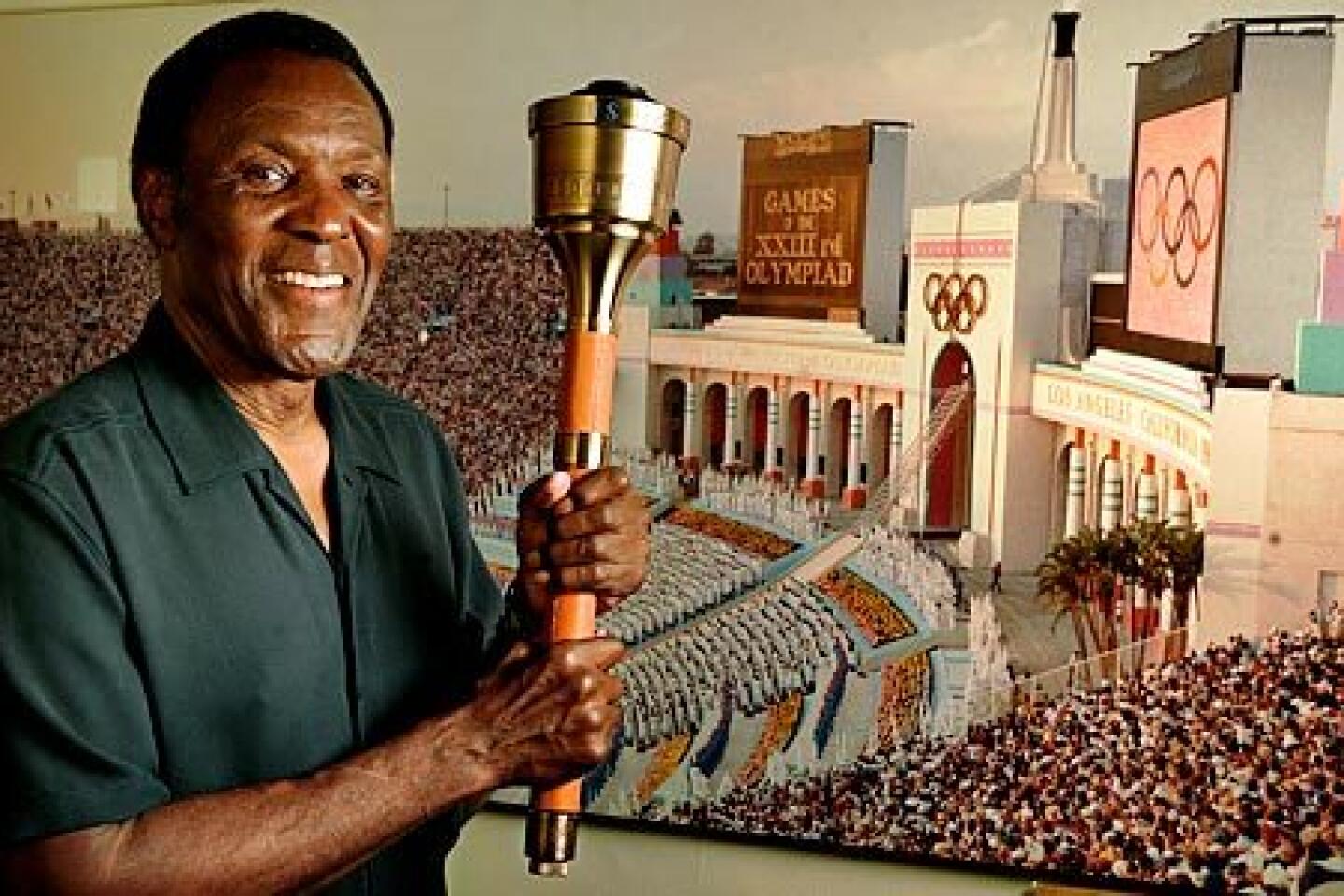

Joseph Shabalala, founder of the South African a cappella vocal group Ladysmith Black Mambazo, whose breathtakingly complex and scintillating harmonies shot the group to global fame in the 1980s when the members were featured prominently on Paul Simon’s blockbuster album “Graceland,” has died in Pretoria. He was 78.

No cause of death was cited in an announcement posted Tuesday on the group’s social media accounts. “Bhekizizwe Joseph Shabalala, Our Founder, our Teacher and most importantly, our Father left us today for eternal peace. We celebrate and honor your kind heart and your extraordinary life. Through your music and the millions who you came in contact with, you shall live forever. From the stage after every show, you shared your heart...’Go with Peace, with Love and with Harmony’.”

Shabalala created the ensemble that would eventually be known as Ladysmith Black Mambazo (“the black axe of Mambazo”) in 1958, focusing on the sound indigenous to the region around Durban, outside which Shabalala was born and grew up in the district of Ladysmith, Emnambithi.

“The music is called Cothoza Mfana or Isicathamiya,” according to press materials for the group’s 1988 Grammy-winning album “Shaka Zulu.” “The words have no direct English translation, referring instead to a kind of dance, a walking on one’s toes, softly, as if not to be heard. It is a sharp contrast to the fierce and aggressive stomping dances traditionally associated with the Zulus.” The phrase “Cothoza Mfana,” however, loosely translates as “tiptoe guys,” a concise description of the footwork that accompanies their vocal acrobatics.

The Isicathamiya sound traditionally was an all-male endeavor that emanated from dormitories in South Africa where men traveled, often hundreds of miles from their homes, to find work in that country’s gold and diamond mines.

At night, they would sing together, and a rich harmonic vocal tradition developed in songs of yearning for those they left behind, and of their struggles to earn a living in harsh conditions in the mines, amid the institutionalized system of racism that was apartheid.

Born Bhekizizwe Joseph Siphatimandla Mxoveni Mshengu Bigboy Shabalala on Aug. 28, 1941, in Ladysmith township, Shabalala initially started singing with a popular group called the Highlanders in the late 1950s when, in search of work, he migrated to Durban, about 200 miles from Emnambithi. After returning home in 1958, he started his own group, which he called the Durban Choir, and consisted of siblings and cousins from three families in and around Ladysmith.

Starting out entertaining at family gatherings in Emnambithi, Shabalala’s group soon found itself in demand for performances at area radio stations, and, after adopting the name Ladysmith Black Mambazo, ultimately released its debut album, “Amabutho,” in 1972, the first of more than 60 the group has made.

Ladysmith became a favorite of South African activist, political prisoner and later President Nelson Mandela, and he invited the collective to sing at his inauguration in 1994, after traveling with him to Norway when he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

The group’s multilayered sound, expressed in everything from harmonized whispers to piercing, goose-bump-inducing falsetto flutters — a geographically distant cousin to the street-corner doo-wop sound African American singers popularized in the 1950s. An equally distinctive hallmark of the group’s performances — along with Shabalala’s mile-wide smile — have been its invigorating choreography, entailing athletic footwork and fluid full-body swoops and bends, all while the singers matched voices flawlessly.

Ladysmith caught Simon’s ear in the early ‘80s as he delved deeper into his explorations of different strands of world music, captivating him sufficiently to invite Shabalala to contribute to the album for which he traveled to Africa in the mid-1980s to collaborate with various musicians.

“The music captured the soulfulness and vitality of the South African experience, and indeed, the sound was built upon traditional Zulu vocal elements that had been embraced for years by the country’s mineworkers,” former L. A. Times pop music critic Robert Hilburn wrote in his 2018 biography “Paul Simon — The Life.”

“Ladysmith had considerable success in South Africa in the 1960s — the first black South African group to earn a gold album for 25,000 sales — but it was still largely unknown outside of its native land when Simon arrived in the country.”

Nevertheless, so enamored of the group’s music was Simon that he initially “was too intimidated to approach Ladysmith.” Still, someone at one of the recording sessions that were underway arranged for an introduction between Simon and Shabalala.

“The rapport was instant,” Hilburn wrote. “Shabalala was warm and gracious, and Simon was charmed when the singer gave him a bagful of Ladysmith tapes. Finally, Paul worked up enough courage to ask if it would be OK if he would write a song for Ladysmith when he got back to the States and send Shabalala a tape of it. The offer came with no strings attached: Shabalala would change it any way he wanted, or he could throw it away.

“Of course, Shabalala told him, ‘Please send a song,’ and the two men embraced,” according to Hilburn. “It was, Shabalala said later, the first time he had ever hugged a white man.”

For his part, Shabalala said of that game-changing meeting, “First of all, when I heard that one of the greatest American musicians of all time wanted to meet with the leader of Ladysmith Black Mambazo, I was shocked and surprised.

“Secondly, when I finally met him and learned from him that he was a fan of Black Mamabazo, and wanted to know if I could record with him, this was a dream come true,” Shabalala wrote in the notes for the 1988 album Simon produced for the group, “Shaka Zulu.” “Much has happened to Black Mambazo since that time and we are honored that this project has given our music an opportunity to be heard all over the world. ... As we say in the Zulu language, ‘Unculo uthokozisa abadababukileyo,” meaning, ‘Singing makes all the sad people happy because it is the voice of happiness.”

The tape Simon sent originally became the song “Homeless,” which he invited Ladysmith to record with him in London, at the famed Abbey Road Studios used by the Beatles. “Simon didn’t want to return to Johannnesburg,” Hilburn noted, because “he couldn’t tolerate any more of the harsh apartheid regime.”

With the cross-continental music that emerged in songs such as “Homeless” and “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes” on Simon’s album, the group was invited to perform in the U.S., notably in high-profile spots on NBC’s “Saturday Night Live” that helped turn Shabalala and his compatriots — most of whom were family members — into global superstars.

They were signed to the same major U.S. label Simon was on at the time — Warner Bros. — and released a string of albums of their own. Those albums focused mostly on Shabalala’s own songs but also included an arrangement of the American gospel standard “Amazing Grace” that Simon created for the group.

In the liner notes of one of those releases, “Journey of Dreams” in 1988, Shabalala wrote, “This Journey of Dreams began a long time ago on the farm and children would come to my dreams and sing to me. Now that we have made this record working with [producer] Russ Titelman and blessed by Paul Simon’s guidance, I feel the dreams are now living inside the music as never before.

“For the first time I have made the music on record exactly as my dreams would tell me and for this sound I am grateful. Because the world listens now and that means the Journey of Dreams goes on and on.”

The group’s newfound fame manifested in many ways. In 1988 Ladysmiyth was invited to perform in Michael Jackson’s film “Moonwalker,” they appeared on “Sesame Street” and sang the South African pop song “Mbube” (which evolved into “The Lion Sleeps Tonight”) for the opening of Eddie Murphy’s 1988 film “Coming to America.”

The ensemble went on to earn 17 Grammy Award nominations and five wins for its own recordings, in addition to sharing in the spotlight from the five Grammy nominations and two wins — including album of the year — heaped on the “Graceland” album.

In addition to the validation represented by the Grammys, Ladysmith did residencies in the 1990s at Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theater Co., helping create a production, “The Song of Jacob Zulu,” for which their score was nominated for a Tony Award and won a Drama Desk Award.

The same year Ladysmith sang for Mandela’s inauguration, Shabalala established an academy to teach traditional South African culture to young people to help keep those traditions alive in the aftermath of the dismantling of apartheid.

A 2000 documentary about the group “On Tiptoe: Gentle Steps to Freedom,” was nominated both for Academy and Emmy awards.

Tragedy struck the group in 2002 when Shabalala’s wife of 30 years, Nellie, was killed by a masked gunman, and Shabalala was injured attempting to protect her. One of his sons, and Nellie’s stepson, was charged with hiring a hitman to carry out the slaying ; he later testified that police offered him a reduced sentence if he would implicate Shabalala. Shabalala also lost a brother, Ben, in 2004 when he was killed in a suburb of Durban, echoing the shooting death of another brother and Ladysmith member, Headman Shabalala, by on off-duty white police officer in 1991.

Ladysmith has continued to tour internationally without Shabalala and is scheduled to perform in June. No services have been announced.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.