Miss Mercy, colorful L.A. rock fixture and cofounder of Frank Zappa’s GTOs, dies at 71

- Share via

Miss Mercy, the effervescent rock ’n’ roll superfan who found fame as a member of Frank Zappa’s “groupie” girl-group the GTOs (Girls Together Outrageously), died after a long illness on Monday, at age 71.

Mercy’s death was announced by her former bandmate, Pamela Des Barres, on Instagram.

“She was a gypsy, the Mae West of the group,” said Alice Cooper, who was also signed to Zappa’s Straight Records and went out with the GTOs’ Miss Christine. “Mercy had the sarcastic one-liners.”

While they worked as a support act to Cooper, the Stooges and New York Dolls, the GTOs were less rock band than femme-positive thought experiment and art prank; Rolling Stone would describe them as a “sociological creation of Frank Zappa’s” in a February 1969 cover story on “rock groupies.” But, in presence and attitude, the GTOs also paved the way for the rowdy all-female groups that emerged in L.A. after them, like the Runaways, the Go-Go’s and L7.

Mercy, born Judith Peters in Burbank, on Feb. 15, 1949, was a fixture on the Los Angeles music scene for over 50 years. Possessing an encyclopedic knowledge of obscure acts and rare sides, she led a wild, untrammeled life in the ’60s and ’70s counterculture and became an influential figure and style icon herself. She was briefly married to reclusive guitar prodigy Shuggie Otis, with whom she had a son, Lucky.

While associated with the underground rock scene, Mercy’s first love was R&B and soul, music that won her heart as a teenager growing up in San Mateo, Calif., listening to “The Wolfman Jack Show” on “border blaster” station XERB. Prior to that, she led a peripatetic life, bouncing from state to state as her father, an insurance salesman with an addiction to amphetamines and horse racing, uprooted the family to outrun gambling debts. A family doctor who prescribed Mercy diet pills as a child for weight issues inadvertently initiated her decades-long relationship with narcotics.

Documentary on the ’80s band “The Go-Go’s.”

She ran away to San Francisco at 15, in 1964, jettisoned her birth name for Mercy, after the Don Covay song “Mercy, Mercy” and adopted an elaborate and unique personal style, influenced by her association with the Charlatans, a psychedelic jug band who dressed like Victorian dandies filtered through the American Wild West. Mercy scavenged velvet opera dresses from thrift stores in the Fillmore District, customizing them with lace, sashes, leather fringe, amulets and charms and began wearing “raccoon” eye makeup — face powdered white, eyes heavily rimmed with kohl — an homage to both silent movie vamp Theda Bara and Australian artist and beatnik model Vali Myers.

The first band to turn Mercy’s head were the Rolling Stones, whom she saw at a December 1965 concert in Sacramento, at which Keith Richards was shocked by an ungrounded microphone stand, saved from instant death only by the rubber soles of his Hush Puppies. After the show, Mercy trailed the band members to their motel and hung out with Brian Jones. In 1966, she spent six months in a San Mateo juvenile hall for truancy. Her parents, she said, “thought jail’d be good for me.” While on probation, she ran away again, to Laguna Beach, and from then on she followed the music wherever it led. A photo of her by Baron Wolman as the prototypical flower child, sitting barefoot in the grass next to her Native American boyfriend, Bernardo, at a 1967 San Francisco be-in, Gathering of the Tribes, was featured on the cover of an early issue of Rolling Stone.

In Los Angeles, she met sculptor and dancer Vito Paulekas, king of the L.A. “freak scene,” and befriended one of his troupe of dancers, Christine Fryka, who became Frank Zappa’s live-in housekeeper. When Mercy came to visit, the mustachioed maestro took one look at her and decided she needed to join the GTOs, the girl group of young, female Hollywood scenesters he had masterminded. “I was not a big Zappa freak,” Mercy said. “I’m not into gimmicks. I was a big gimmick myself, but I was not into people like me.”

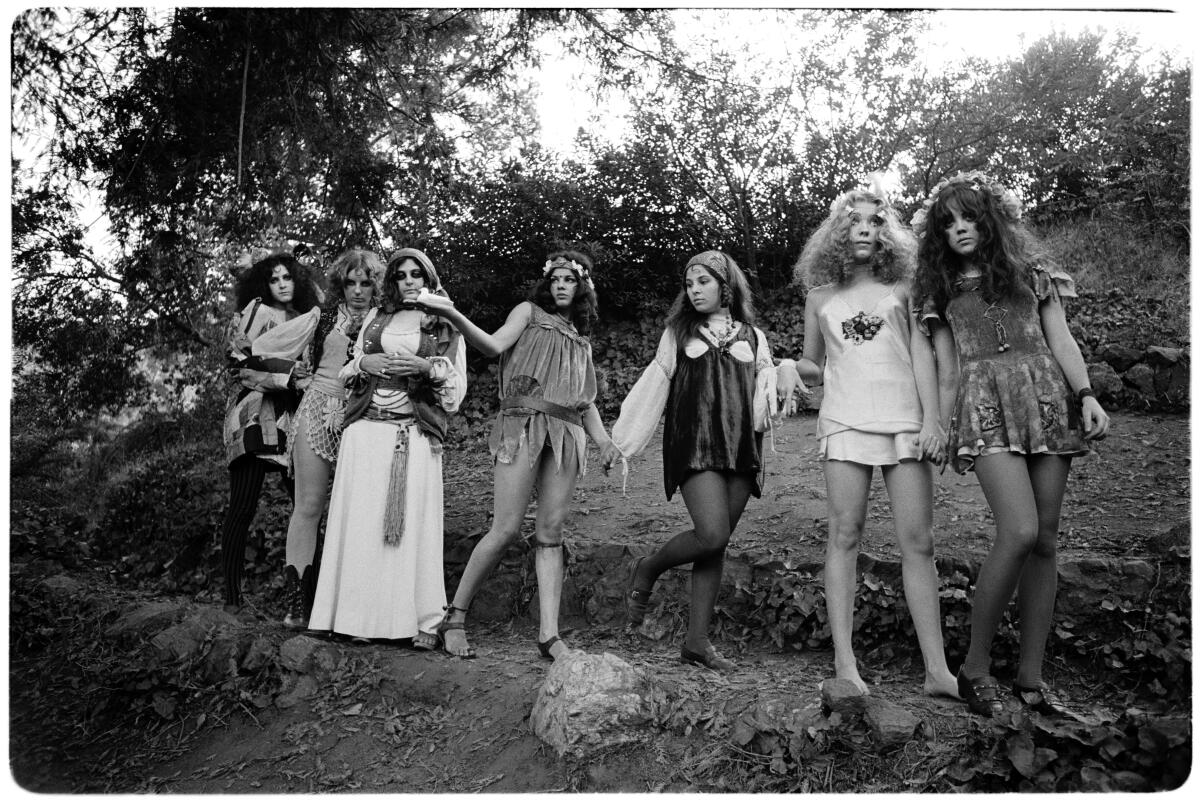

A starkly unconventional plus-size beauty with undeniable star charisma, Miss Mercy stood out among the seven members of the GTOs, who were given courtly titles by ’60s troubadour Tiny Tim, and also included Miss Pamela (Des Barres), Miss Christine (Fryka) and Miss Cynderella (a.k.a. Cynthia Sue Wells, who later married Velvet Underground cofounder John Cale).

Zappa coproduced the group’s only album, a collection of half-baked skits and songs, which Mercy titled “Permanent Damage” — because that’s all she saw around her, people permanently damaged by their environment. Mercy and Des Barres befriended Gram Parsons and his group the Flying Burrito Brothers and sang backup on ”Hippie Boy,” the closing song on their debut album, “The Gilded Palace of Sin.” She also made an appearance in the Jimi Hendrix film “Rainbow Bridge.”

The GTOs fame was such that when Mercy got busted for possession of morphine in early 1969, it made the pages of Rolling Stone. But her drug habit almost took a fatal turn in October 1970 when a young French aristocrat named Jean de Breteuil gave her a shot of heroin so pure she nearly overdosed. Unknown to her, his previous port of call was to Janis Joplin, at the Landmark Hotel, who was felled by the same batch of dope.

After a stint in Memphis, during which she became part of the coterie of R&B musicians around Stax and Hi Records, including the Bar-Kays and Al Green, she returned to L.A. and spotted teenage guitarist Shuggie Otis, on the cover of “Super Session: Volume 2,” a 1970 album recorded with Al Kooper. They began a relationship and were married in the early ’70s by Shuggie’s father, Johnny Otis, a bandleader and ordained minister, in the living room of the family home in West Athens. Their son, Lucky, was born in 1973, but their union was short-lived.

A few years later, Mercy found her place as a stylist and hairdresser of bands in the nascent Los Angeles punk and rockabilly scene, whose prime movers were rabid music fans steeped in rock ’n’ roll mythos. While nursing her cancer-stricken mother in the mid-’80s at her sister’s house in Lake County, Calif., Mercy became addicted to crystal meth. Returning to an L.A. awash with crack cocaine, she became addicted to that also. She hooked up for a time with Arthur Lee, the brilliant but troubled frontman of ’60s group Love, who had just been released from prison after serving a sentence for arson and was also addicted to crack.

Liz Phair was supposed to be on tour with Alanis Morissette right now. Instead, she’s interviewing the “Jagged Little Pill” star for The Times.

At one point living out of a shopping cart on skid row and on a hill beside the Hollywood Freeway — circumstances she hid from her family and social circle — she tired of the insecurity and chaos of the drug lifestyle. She got sober on Thanksgiving Day 1998, joined straight society and never left, working in the receiving department at the Goodwill store on Hollywood Boulevard in Los Feliz, sorting new donations. Her colorful history was well-known by co-workers, who nicknamed her “the Legend.”

Her love of music and unabashed enthusiasm for new scenes and sounds never waned. A witty and compelling raconteur, Mercy worked in recent years with journalist Lyndsey Parker on a memoir, “Permanent Damage,” which will be published by Rare Bird Lit in 2021.

Although the GTOs were commonly known as “groupies,” Mercy took issue with the sexual connotations of the term. “It wasn’t that I wanted to go to bed with everybody,” she said. “I wanted to know and be with the people I thought were making the best music and see it from behind-the-scenes. I just wanted to know how they did it and what was going on.”

“She was a super-survivor, she knew the street and how to work the street,” said Cooper. “Mercy had a life force inside her that didn’t burn out.”

Mercy is survived by her son, Lucky Otis.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.