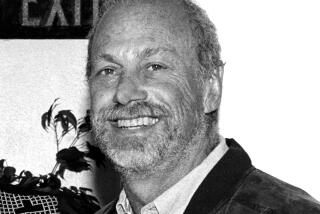

Al Schmitt, Grammy Award-winning engineer behind countless classics, dies at 91

- Share via

Although it feels touched by the sublime, Sam Cooke’s R&B banger “Twistin’ the Night Away” didn’t land onto tape itself, nor did surf band the Astronauts’ “Baja,” composer Henry Mancini’s “Theme for ‘Peter Gunn,’” songwriter Jackson Browne’s “These Days,” soft rock band Toto’s “Africa” or any of the other classic songs produced, engineered or mixed by Al Schmitt.

Schmitt, who with 23 Grammy Awards including a 2006 Recording Academy Trustees Award and two Latin Grammy trophies, holds the record for the most wins in the engineering category, died Monday at 91. His passing was announced in a Facebook statement by his family. No cause of death was given.

Friends since the ‘90s, two of rock’s grandes dames gather to discuss Faithfull’s new album, “She Walks in Beauty,” and their near-death experiences in 2020.

“My idea of a good time is to be in the studio with 65 musicians or more,” Schmitt told one interviewer. His technical acumen and hitmaker’s ears afforded him that opportunity. In addition to the classics mentioned above, Schmitt engineered recordings by Liza Minnelli, Thelonious Monk, Ray Charles, Dr. John, Barbra Streisand, Natalie Cole, Michael Jackson, Tony Bennett, Duane Eddy, Martin Denny, the Drifters, Dion, Linda Ronstadt, Johnny Cash, Pablo Cruise, Al Jarreau, Joao Gilberto, Glen Campbell, Michael Bolton and Keith Jarrett.

He did much of that work at famed Los Angeles recording rooms including Capitol Studios on Vine Street, RCA Studios on Sunset Boulevard and the Village Recorder in West L.A.

One magazine ad for Neumann microphones described Schmitt as “Loved by the Chairman, the King, the Material Girl, some Hot Tuna and everyone aboard the Airplane.” Translated: Schmitt’s invisible touch guided records by Frank Sinatra, Elvis Presley, Madonna, Hot Tuna and Jefferson Airplane, part of a discography that tallies more than 140 gold and platinum songs.

As a producer, Schmitt earned credits on albums including Jefferson Airplane’s “Volunteers,” Browne’s “Late for the Sky,” Neil Young’s “On the Beach,” George Benson’s “Breezin’” and Diane Schuur’s “Loved Walked In.”

On social media, Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys celebrated the engineer’s life, writing, “I feel bad about Al Schmitt passing. Al was an industry giant and a great engineer who worked with some of the greatest artists ever, and I’m honored to have worked with him on my Gershwin album.”

Another measure of Schmitt’s skills? When Bob Dylan tried to hire a then 80-something Schmitt to work on Dylan’s 2015 album “Shadows in the Night” and Schmitt was forced to pass due to scheduling conflicts, Schmitt recalled to Sound on Sound, “the very next day I got a call back, saying that [Dylan’s management] were prepared to move their schedule to a time when I was available, because Bob really wanted to work with me. Evidently he’d heard my work, including the ‘Duets’ album I had recorded with Sinatra, and he must have figured that I was the right guy to record it.”

A deluxe reissue of ‘John Lennon / Plastic Ono Band’ details Lennon’s primal scream therapy and the album’s surprisingly playful recording sessions.

Though hardly modest about his accomplishments, Schmitt said his good fortune multiplied with each hit in part due to the major perk of success in the music business: “You get to work with successful people,” Schmitt told Studio Sound magazine in a 1996 interview. Successful people, he explained, have the budget to hire the best musicians and record in the best studios with the best equipment. The unlucky others, by contrast, are “working with a guy who doesn’t know how to tune his drums, they’re using this little schlocko board and a bunch of cheap microphones, and then they wonder why their stuff doesn’t sound as good as Al Schmitt’s. Well, there’s an obvious reason. I’ve got all of the benefits.’”

Born Albert Harry Schmitt on April 17, 1930, in Brooklyn, New York, he seemed fated for the record business: His uncle founded and owned Harry Smith Recording, the first independent audio facility on the East Coast. The studio where the Charlie Parker All Stars recorded their crucial 1948 release “Bop Session With Charlie Parker,” HSR afforded Schmitt the opportunity to learn the art of capturing the sound of a big band, all surrounding a single monaural microphone, onto an acetate record.

One of his first major sessions happened by accident. Assigned weekend duty giving tours while working at Manhattan’s Apex Studios, he was blindsided to see Duke Ellington enter the studio with his band and start setting up. Thinking there was a scheduling mistake, Schmitt approached Ellington and explained that he was an unprepared novice. “I kept saying to him, ‘Look, I’m not qualified to do this. Someone made a mistake here but I can’t get hold of anybody.’ But he just patted me on the back and said, “Don’t worry son, we’re gonna get through this. Just relax.’”

After serving in the military, Schmitt returned to New York and became famed producer Tom Dowd’s engineer. Schmitt relocated to Los Angeles in the late 1950s and got a job at Radio Recorders on Santa Monica Boulevard in Hollywood. He spent much of his professional life in one of two recording facilities located a few blocks down Vine from one another: RCA Studios and Capitol Studios.

By the time he established himself in Los Angeles, stereo recording had upended the business and further sealed the engineer’s status when it came to making records. In audio recording, an engineer is responsible for picking and placing microphones, ensuring that the sound passing through them moves unimpeded through the mixing board and onto a tape recorder. Which is to say, Schmitt’s work was defined less by his presence than his absence. If you can hear an album’s engineering, somebody messed up.

Crucially, though, a great engineer can add volumes to a recording by appreciating the relationship between a room, a microphone and the sounds musicians make. As the guitarist and recording studio expert Deke Dickerson noted in a Facebook post, when Schmitt was working at Radio Recorders he innovated by becoming “the first engineer on the West Coast to put a microphone on a kick drum. Until that point, drum kits were usually recorded with one simple microphone over or near the kit. When Al was recording a jazz band and heard the drummer doing syncopated rhythms on his kick drum, Al put a mic on the kick. Soon thereafter, it became a standard practice.”

Season two of Tyler Mahan Coe’s “Cocaine & Rhinestones” podcast focuses on country great George Jones: “His chest cavity glowed with so much air.”

Schmitt thrived at RCA, facilitating Duane Eddy’s twang-bar instrumental hits, engineering collaborative sessions between jazz singer Rosemary Clooney and mambo king Perez Prado and working with Mancini during his string of early 1960s instrumentals. Schmitt won his first Grammy in 1962 for engineering the recording of Mancini’s “Hatari.” He was behind the boards during the “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” score recording, and engineered the sessions for the TV show “Bonanza.”

Describing an Eddie Fisher project in the late 1960s at RCA on Sunset, he recalled: “I’d be doing orchestral overdubs with Eddie from 2 until 5 [p.m.], then I’d go up to my office and meditate a little before working with the Jefferson Airplane until 4 in the morning. After that I’d grab a little sleep, come back in and do my paperwork, relax a bit and then it was back to Eddie Fisher. It was very weird.”

After RCA Studios shuttered, Schmitt moved to Capitol, where he engineered dozens of recordings, many produced by the late Tommy LiPuma. Among those whose work he recorded at the studios were Sinatra, Willie Nelson, Luis Miguel, Diana Krall, Herbie Hancock and Anita Baker. At the Village Recorder, Schmitt engineered Steely Dan’s “Aja.”

In a statement, Patrick Kraus, Universal Music Group’s senior vice president of recording studios and archive management, called Schmitt “one of the most accomplished engineers and producers who ever walked into a recording studio. Al worked with iconic artists on some of the biggest albums of all time.” He added, “It’s hard to imagine Capitol Studios without Al at a console, dialing in a mix, catching up with one of his many friends or lighting the place up with his smile and laugh. He will be deeply missed.”

When Schmitt became the first recording engineer to get a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, producer Don Was explained the legend’s importance by saying, “Let there be no mistake about it, it takes a beautiful cat to consistently make such beautiful records. I can think of no other figure in the entire music business who is as loved and respected as Al Schmitt.”

Schmitt is survived by his wife Lisa, five children, eight grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

The family’s statement noted, “The world has lost a much loved and respected extraordinary individual, who led an extraordinary life. The most honored and awarded recording producer/engineer of all time, his parting words at any speaking engagement were, ‘Please be kind to all living things.’”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.