The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

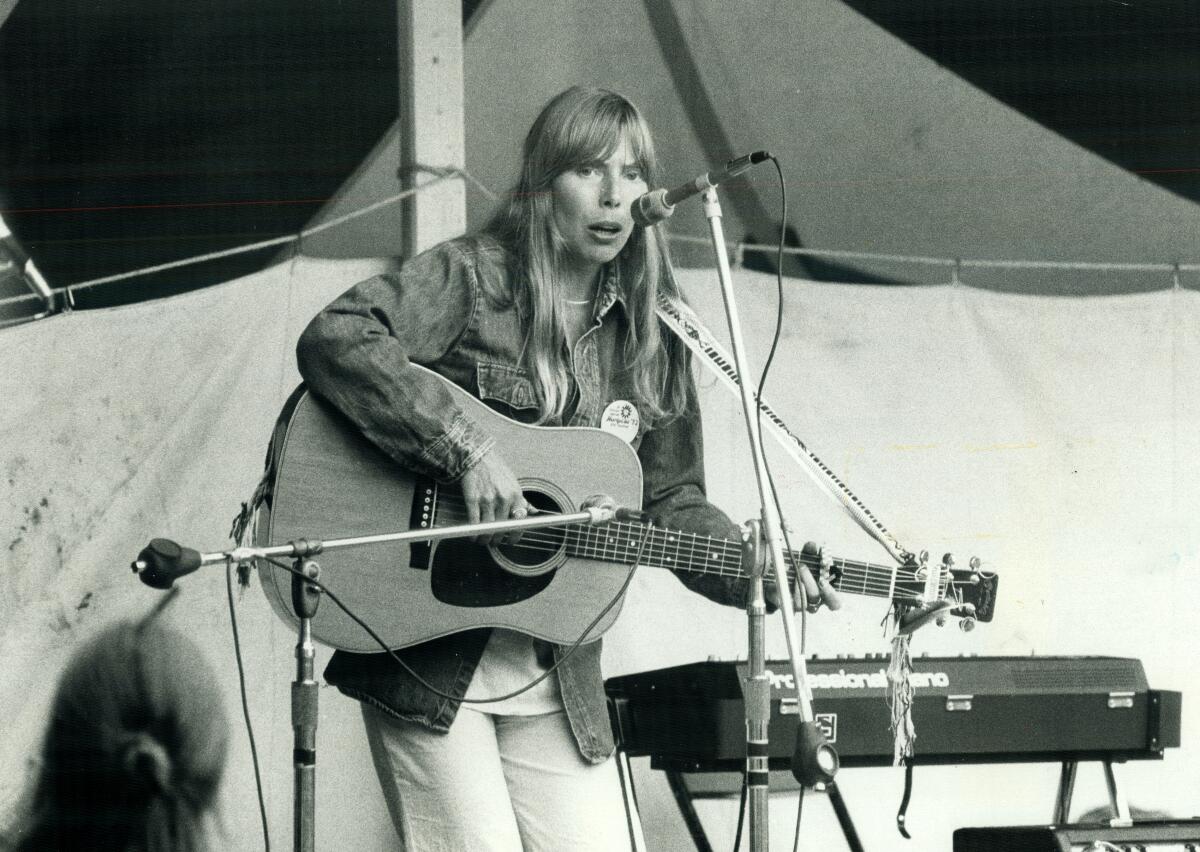

Joni Mitchell was, as ever, in a philosophical mood. During the first print interview she gave following the 1971 release of her fourth album and masterpiece, “Blue,” she wondered, like she did in so many of her songs, whether it is actually possible to be both fulfilled and free. “Freedom ... implies always the search for fulfillment, which sometimes is more exciting than the fulfillment,” she mused in Sounds magazine. She mentioned her soul-journeying friends — which included the Laurel Canyon rockers who helped inspire her to shake off what little was left of her folk dust, embrace her own sturdy rhythm and delightfully proclaim, “I want to wreck my stockings in some jukebox dive” — who would come to her and say “they FOUND IT!” Two weeks later, they’d be unsatisfied. “Because they’ve come to enjoy the quest so much,” she said. “They’ve found it — then what?”

Could there be another way to regard the very nature of fulfillment? “I don’t think it necessarily means trading the searching,” Mitchell added.

Such was the restless dream of “Blue.” Mitchell sang herself into motion. She honored emotions as sources of knowledge. A lover of painting and jazz — of Miles Davis and Picasso, both of whom had their “Blue” periods too — she knew the potency of tone: of finding the correct register of a feeling. She twisted the knobs of the guitar until they sounded as inquisitive as she felt, and within her suspended chords, which she called “chords of inquiry,” she spoke straight to us. She wrote, in a possible nod to Nietzsche (after whom she named her cat), of her very blood. And as her words enacted a kind of emotional ekphrasis, getting to the core of her desires through precise details, her music itself — her prismatic piano playing, her narrative harmonies and the liminal charge of her dulcimer — told “Blue‘s” vagabond stories too: skating on a river, alone at sea, swaying with an unfamiliar breeze. “I was used to being the whole orchestra,” she would later note. Her voice conducted: bringing light to “California” or indignation to “hate” or wings to “fly.” Mitchell confronted her own complexity and put it into every note.

In a rare interview, Joni Mitchell talks with Cameron Crowe about the state of her singing voice and the making of “Blue,” 50 years after its release.

A law of patriarchy has always been to sweep the details of women’s lives under the rug. Joni revealed them. The specificity of her lyrics — the proper nouns and dialogue that charted her wishes, doubts, secrets and regrets, that supported her belief in romantic love as an intellectual endeavor, that positioned the unconventionality of her “dark cafe days” against, say, the “dishwasher and coffee percolator” of a man’s new life on “The Last Time I Saw Richard” — created a mirror into which we can still look and feel seen. Through it all, Mitchell assembled the vocabulary of autobiographical songwriting, setting a blueprint for what has been said in popular music ever since. Björk once posited that it was Joni who first “had the guts to set up a world driven by extreme female emotion.” “Blue” was its genesis.

Starting out a decade before “Blue” as a hobbyist folk singer in a Calgary coffee shop called the Depression, Mitchell had sharpened her mind as a method of survival. She suffered from polio as a child of the Canadian prairies, and by her early 20s she had both given up a daughter for adoption (“I had to kind of hide myself away,” she said of her pregnancy) and escaped a stifling marriage to a husband who, she sang on 1968’s “I Had a King,” had “taken to saying I’m crazy.” “I started writing to develop my own private world, and because I was disturbed,” she once said. In time, she aspired to the first-person poetry and biting colloquialism of Bob Dylan, calling (of all Dylan tunes) the vindictive “Positively 4th Street” her key: “Now we can write about anything,” she thought.

With “Blue” she said anything she wanted and reproduced that key infinitely. She didn’t look back. Mitchell once critiqued the contemporary visual art of the 1970s for being “noncommunicative”; on “Blue,” communication became a virtue. The openness of her self-determined chords matched what she was reaching for in her lyrics. The absolute clarity of her voice — through which she transposed the crescendoing drama of classical music, the episodic emotionality of jazz and the immediacy of rock — emphasized the transparency of her words during a time when she felt, she said, “like a cellophane wrapper on a pack of cigarettes.” “I was demanding of myself a deeper and greater honesty, more and more revelation.”

If she was going to be famous — and “Blue” grapples eloquently with the increasingly mediated nature of the counterculture, with its absurdities and tragedies both — then people “should know who they were worshiping.” That extended to “Little Green,” the mystic ballad she wrote about the daughter she gave up for adoption. It extended to her simple but radically honest declaration, on “River,” that “I’m so hard to handle / I’m selfish and I’m sad”; to her position as “a lonely painter,” as she sings on “A Case of You,” who lives “in a box of paints.” And it extended to the melancholy shimmer of the interstitial “Blue” — with its opening notes, inspired by Miles Davis, that she likened to a “muted trumpet tone.” Its tale of a woman unmoored — “Crown and anchor me / Or let me sail away” — was “a metaphor for the actual situation for women at the time,” she told author Michelle Mercer in the 2009 book “Will You Take Me as I Am.” “You were supposed to be tied down.”

Written in flight, “Blue” was Joni’s travelogue at the crossroads of the world and her soul. She had dodged another marriage proposal in 1970 and taken off, in pursuit of herself, to the Grecian island of Crete, to Spain and to France, with her dulcimer in hand. And while she wrote songs about the groovy characters (and one eccentric thief) she encountered on her route, the transience was all in service of her introspection, of her songs about the quietly epic nature of being a woman alone in public, reading in the park, writing in dark cafes. Our music-obsessed protagonist — after “that scratchy rock ’n’ roll,” whether under a Matala moon or the California sun or her “headphones up high” — dreams of a rented room filled with flowers and her thoughts in bloom. “I write rhyming little movies,” she once said. “I’m the playwright and the actress.” Set in beachside caves and tourist towns, she was auteur and star as the bohemian woman wanderer, adventuring inside and out as an antidote to heartbreak and existential longing. Maybe French filmmaker Agnès Varda agreed when she positioned a copy of “Blue” in the background of a scene in her 1977 film, “One Sings, the Other Doesn’t”: Joni invented a new paradigm for independent women of heart and mind.

“Blue” was profoundly in between. It was between conventional chord structures, between cities and streets, between sky and ground, between relationships, between bitter and sweet. It was in between hating someone and adoring them, in between forgiveness and self-respect — “I love you when I forget about me,” she sang on “All I Want” — in between the unknowns she plumbed and the exactitude of her language.

She preferred suspended chords for a reason: They carried her, like the wind. “They have a question mark in them,” she said of those chords. “They feel like my feelings.” “Men need to solve things and come to conclusions,” she said, but “my life was full of questions.” She was comfortable sitting with discomfort. The conflicted inner monologue of “This Flight Tonight” finds her midair and meditating on whether “love is just mythical.” In the shadows of “The Last Time I Saw Richard,” Mitchell ends the album insisting on her solitude — “I’m gonna blow this damn candle out / I don’t want nobody comin’ over to my table” — and on her time to think. “There were so many unresolved things in me,” she said. “I’d stay in unresolved emotionality for days and days.”

We asked 10 of our favorite artists to each choose one track from Joni Mitchell’s ‘Blue’ and describe what makes the song and artist so indelible.

“Blue” proved that to know yourself is to be so attuned. Can you imagine a lover actually telling you (Shakespeare reference notwithstanding) that he’d be “as constant as a Northern Star,” as Mitchell narrates on “Blue‘s” peak, “A Case of You”? Radiant, a guidepost, but so distant as to be over 300 light-years away? She responded with 16 quick-witted lines that raised the bar on her lover’s poetic charms and on pop lyrics forever. “Constantly in the darkness? Where’s that at?” Mitchell sings, bending the night into a question too. “If you want me I’ll be in the bar.”

Joni Mitchell does not live in the dark. She created illuminated pop literature, saying that to be lost — to ask difficult questions instead of dismissing them — is to be alive. She mixed shades of sadness and wisdom into a palette of nerves and melody that does not feel unreasonable to call sacred. When she sings, on “A Case of You,” that “part of you pours out of me in these lines from time to time,” it’s a testament to how love can change you — how, as the poet Anne Carson suggests in her book “Eros the Bittersweet,” “self forms at the edge of desire” — even in the act of self-possession. She trills “you” and “me” into waves, a colorist, as if to emphasize the edges where connection happens. “A Case of You” is about Joni’s contained capabilities too. “I could drink a case of you, darling / Still I’d be on my feet” is a genius way of articulating that she can match this intoxicating person — that she is an equal and then some.

Mitchell didn’t need a North Star, ultimately. On “Blue” she became one. To trace the album’s influence would be to try to box in constellations: “Blue” is everywhere. In writing songs as elemental as any color, she inspired others to do the same: Prince — who covered “A Case of U” — and his purple; Taylor Swift and her “Red.” Swift has called “Blue” her favorite album of all time, and the specificity that makes Swift songs feel like X-rays of our souls, which only grows deeper in her work, owes to that influence. “Blue” is in Lorde on “Melodrama” finding “flowers for all my rooms”; it’s Lana Del Rey rhyming “Rolling Stones” and “Vogues” on her own song called “California.” Her art songs gave way to art rock — “Hey Joni,” sang Sonic Youth’s Lee Ranaldo in 1989, an explicit nod to her alternative tunings — and to the indie rock orbit of Waxahatchee. Mitchell also returned the key to Dylan: “Tangled Up in Blue” was a stated Joni reference. And affirming Joni’s requited love with jazz, Herbie Hancock would go on to record “River” and more on the Grammy-winning tribute “River: The Joni Letters.” Hancock wrote in his memoir that watching Joni and saxophonist Wayne Shorter converse was like “an out-of-body experience.”

The legacy of “Blue” — which the New York Times in 2000 called a musical milestone of the 20th century, and which NPR in 2018 called the greatest album ever recorded by a woman artist — is really that of the whole Joni catalog through the mid-‘70s. She never abandoned the human voice she located on “Blue”; she wrote into and through it. Her next record, “For the Roses,” would be even more lyrically incisive. With the commercial feat of “Court and Spark,” which included her sole top 10 single, “Help Me,” she stuck to her word on “River” — to “make a lot of money” and then “quit this crazy scene.” Mitchell moved on to the visionary jazz-fusion experiments of “The Hissing of Summer Lawns” and the landmark “Hejira,” a sprawling bookend to “Blue” that has become, in recent years, her most influential record. “Blue” made it all possible.

“I am on a lonely road and I am traveling, traveling, traveling,” she sang on “All I Want,” “Looking for something, what can it be?” The answer was Joni Mitchell. And then she kept searching.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.