- Share via

It has been over 65 years since more than 1,500 entertainers were selected for immortality on the sidewalks of Hollywood. Only a couple dozen or so of those original inductees are still with us. Among many of his endurance-based accolades, bandleader Ray Anthony is one of the oldest surviving members of that initial class of Hollywood Walk of Fame stars. (Actress Marsha Hunt, who would have been a senior to Anthony’s freshman, holds the record at 104.)

On Jan. 20, Anthony celebrated his 100th birthday surrounded by friends and Perry Anthony, his lone descendant, a son from his brief marriage to actress Mamie Van Doren. Anthony’s Hollywood Hills property remains as he envisioned it in 1975, complete with lush carpets, a sunken dining room and a view of the ocean, weather permitting. Amid balloons shaped like the number “100” and the arrival of a pizza adorned with the number inscribed in olives, Anthony remarked that “they really wanted to remind me of my age!” Though his hearing has diminished considerably, his memory is still sharp. Amid a flurry of well wishers chiming in by telephone and at the front door, Anthony took time to reflect on his century of stories with a sly sense of self and appreciation for all that he had seen along the way.

After his father handed 5-year-old Ray Anthony a trumpet in their Cleveland home, he was hooked on the horn, eventually becoming a teenage disciple of Harry James, the jazz trumpet-playing actor-bandleader who was only a half-dozen years older than him. While still a teenager, Anthony found himself thrust into the big time as a member of the Glenn Miller Orchestra, a cocky brassman on a bandstand full of world-weary men. He lasted less than two years with the band and was notably fired twice, his strong chops seemingly appealing enough for a second chance but not a third. “Some of the musicians teased me for being so young in the number one band,” recalled Anthony. “He was tough but it’s a business. You don’t have much time to do anything but follow the lines.”

By the end of 1941, the acceleration of the war had disrupted the frivolity of the big band scene and many musicians offered their talents to the home front. As a result, Anthony found himself in the Navy, entertaining the troops at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel in Honolulu, then still a tense battleground.

Anthony emerged from the war with his Hollywood-handsome features and the confidence of a veteran showman, spending the next dozen years on televisions and radios across America. His resemblance to Cary Grant was a punchline for both men. The Ray Anthony Orchestra was a prolific ensemble, releasing countless dance singles in the early 1950s, including “The Hokey Pokey” and “The Bunny Hop” — swinging trifles that captured a national audience almost immediately. His contributions to the lost art of the boogie (“Trumpet Boogie,” “Mr. Anthony’s Boogie,” “Big Band Boogie,”) and the foxtrot, which were often paired with a few dance steps from the enterprising Arthur Murray, were equally successful. Anthony’s occasional trumpet solo breaks were melodic and deliberate but less the result of improvisatory brilliance and more intended to heighten the dance floor frenzy with force rather than filigree. The hours were rigorous and the touring was exhausting, 18 band members and their equipment passing from coast to coast without pause. “If I had to go, they had to go,” Anthony joked.

Perhaps the most legendary of Anthony’s exploits was the 1952 release party for his orchestra’s swooning single “Marilyn,” written for Ms. Monroe, who had yet to become a household name. Befitting the glamour of her ingénue profile, Monroe arrived at the party in a Bell helicopter wearing a radiant pink dress that would have been visible hundreds of feet above the crowd, long before any of the guests knew who was arriving. Even Anthony wasn’t apprised of her planned attendance. In response to whether her then-suitor Joe DiMaggio had joined the other high-profile guests such as Mickey Rooney and Sammy Davis Jr., Anthony noted with a laugh that he “wasn’t invited.” Those little helicopters could only contain so much personality, and the recently unearthed photos of Monroe and Anthony, trumpet in hand, leave little room for anyone else.

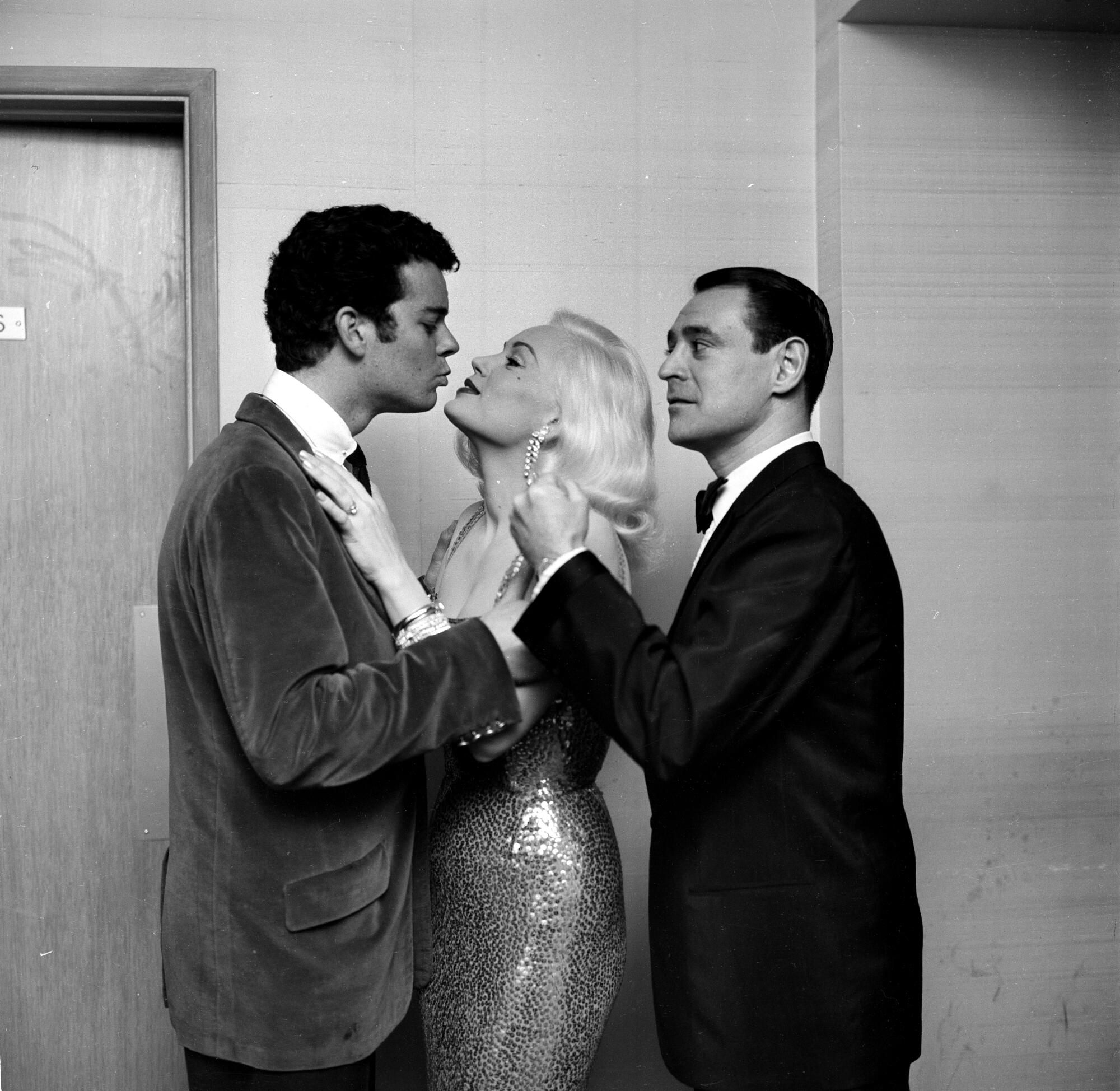

Anthony’s adoration of spiky-heeled Hollywood blonds was a consistent through line in his public and private life. His tumultuous marriage to famed bombshell Van Doren in 1955 was tabloid fodder for the rest of the decade before things spectacularly imploded. But Anthony’s son, Perry, was the positive result of their brief coupling. During the birthday revelry, Perry fondly reminisced about the Beatles albums his father brought home from work. “I wish I still had them now,” he remarked wistfully.

Toward the middle of the 1950s, Anthony studied with acting teachers Estelle Harman and Sanford Meisner. “I needed to get all the help I could get,” Anthony remarked. While acting was never a large focus of his career, he appeared in several notable films including “High School Confidential” and the thrice Oscar-nominated “Daddy Long Legs” featuring Fred Astaire. But it was his appearance in the 1956 teenage call-to-arms “The Girl Can’t Help It” that has had the longest impact.

In one of the funniest scenes in that movie, Jayne Mansfield, in the middle of a recording session, purchases an apple from a vending machine located inside the recording studio and sits down with the Ray Anthony Orchestra as they bounce through “Rock Around the Rock Pile.” At the close of the tune, Mansfield’s character, whose voice has already shattered glass earlier in the film, leans into the microphone for her part as a wailing police siren. The performances by Little Richard and Eddie Cochran spurred impressionable young musicians like Paul McCartney and John Lennon to pursue their rock ‘n’ roll dreams, but it was Anthony’s box office bankability that helped to sell the film to producers.

By the start of the swinging ‘60s, Anthony had already vigorously swung his way through the ‘40s and the ‘50s. During nearly 20 years with Capitol Records, he recorded hundreds of tracks for the label, whose roster included Frank Sinatra and Nat King Cole when he arrived and Grand Funk Railroad and the Beach Boys by the time he left.

Anthony continued to perform regularly into his 90s, sometimes leading his own unit, sometimes joining a super-group of big band veterans. He kept up an eight-decade streak of television appearances as a sort of Barney Rubble to his friend Hugh Hefner’s Fred Flintstone on E!’s “The Girls Next Door” in the early 2010s, but mostly enjoyed the glow of his unparalleled career as a swinging mid-century American cad, poolside parties above Sunset Boulevard at the ready.

Now, 60-plus years after receiving his Hollywood star, Anthony’s trumpet still sits by his bedside, a musical relationship that predates the first transatlantic flight and the presidency of Herbert Hoover. He offered no secrets to his longevity but did note his son’s parents have lived for more than a combined 190 years. (Van Doren turns 91 on Feb. 6.)

It was agreed all around that Perry has inherited some good genes and by all accounts, Mr. Anthony, still playful and cheeky, has had a pretty good century.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.