After 40 years, Prince Estate claims band name ‘Morris Day and the Time’ belongs to it

- Share via

Were it up to him, singer and bandleader Morris Day, best known for his 1980s funk hits as vocalist for the Time, would be rolling into theaters this year beneath flashing marquees announcing the arrival of his band, “Morris Day and the Time.”

Instead, Day, whose rise was facilitated through a relationship with the late Minneapolis artist Prince, took to social media on Thursday to express his outrage at the Prince Estate over his inability to do just that. Claiming that “the people who control his multimillion-dollar estate want to rewrite history by taking my name away from me,” Day made an announcement:

“As of now, per the Prince Estate, I can no longer use Morris Day and the Time in any capacity.”

“I literally put my blood, sweat, and tears into bringing value to that name,” Day wrote, stressing that he and Prince together came up with the concept, one that “while he was alive, he had no problem with me using. … Not once ever saying to me that I couldn’t use that name configuration.”

Commenters lined up to express outrage at Prince’s legal team. “His family doesn’t even run the estate,” wrote former Prince bassist Nik West. “I don’t see how ‘randoms’ can tell you this! Morris Day and the Time forever … we ALL know what time it is!”

Ye’s discography and celebrity mean he can still headline mega music festivals. But his latest outbursts and threats may be too much for fans to bear.

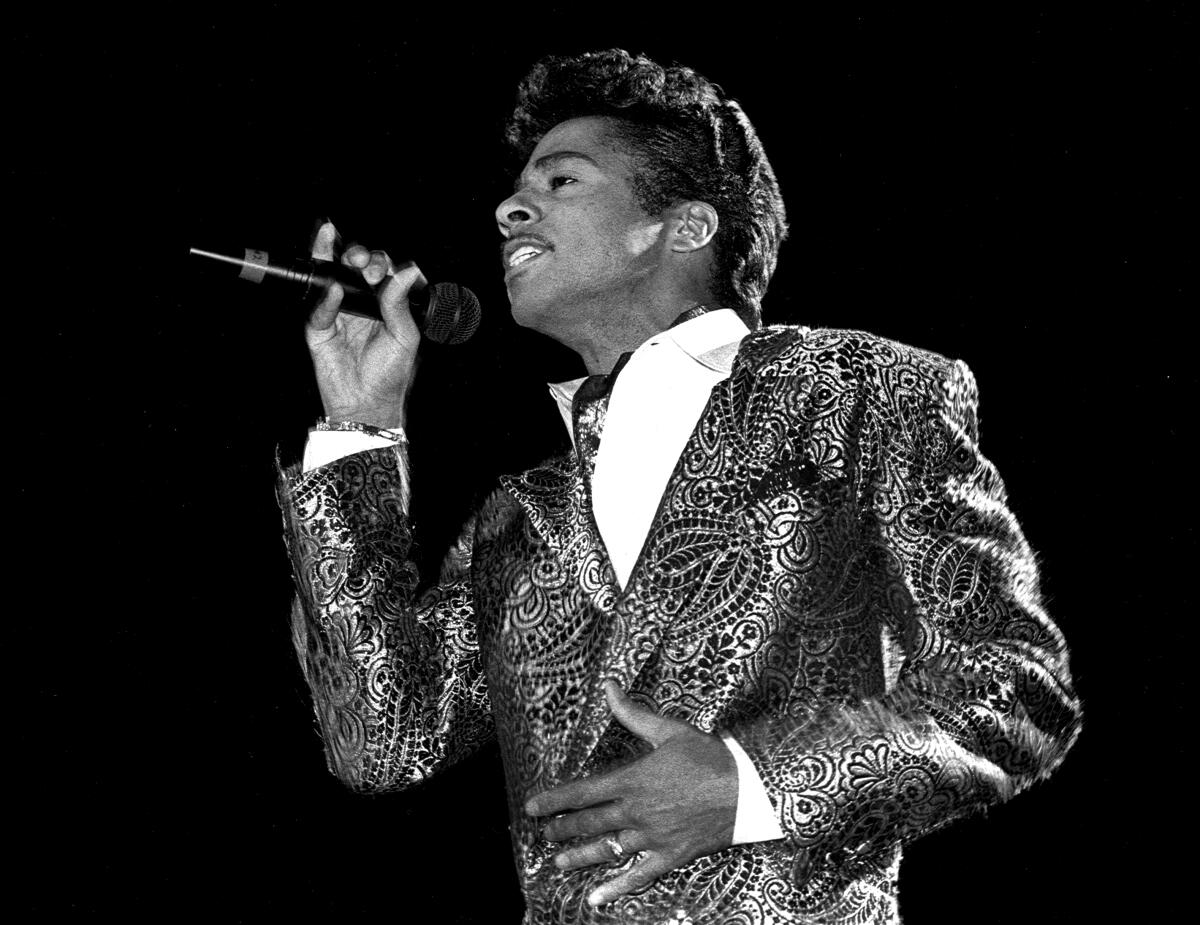

Day is best known for his suave star turn as Prince’s musical competition in the movie “Purple Rain,” in which Day and the Time tear through brilliantly choreographed jams including “Jungle Love” and “The Bird” during a battle of the bands at Minneapolis club First Avenue. Active throughout the 1980s, the Time released a trio of Prince-produced albums, most successfully 1984’s “Ice Cream Castle.” Day’s magnetism, well-coiffed pompadour and ability to summon his wingman, Jerome, with a snap have made him a favorite on the legacy circuit.

The Prince Estate quickly issued a statement in response to Day’s claims, noting pointedly that “the information that he shared is not entirely accurate.”

It wrote, “Given Prince’s long-standing history with Morris Day and what the Estate thought were amicable discussions, the Prince Estate was surprised and disappointed to see his recent post,” adding that it “is open to working proactively with Morris to resolve this matter.”

Day’s attorney, Richard Jefferson, reaffirmed his client’s position in a follow-up statement: “The written agreement between the parties gives our client the exclusive right to continue as Morris Day and the Time and is consistent with Prince’s long-standing consent.”

That long-standing consent goes back to the early 1980s when, under his deal with Warner Bros. Records, Prince built a band. Drawing from a Minneapolis funk group called Flyte Tyme, which included future super-producers Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, Prince brought in a number of new players and wrangled his childhood friend Day for singing duties. Producing and writing or co-writing most of the Time’s songs, Prince shepherded to the market four Time albums between 1981 and 1990. Prince didn’t leave a will, and after his death in 2016, various relatives fought for control. Now co-owned by publishing company Primary Wave and three of Prince’s siblings, the estate was recently valued at $156.4 million.

The legal fisticuffs came a few months after Day, through Jefferson, received a letter from an attorney for Prince’s estate. Sent in response to Day submitting a 2021 trademark claim on use of “Morris Day and the Time,” the letter attached as a reference Day’s original Oct. 19, 1982, contract with Prince’s company PRN Music Corporation. The legal notice emphasized that “Mr. Day has no right to use or register THE TIME in any form” and that the estate is “sole and exclusive owner of all rights” involving use of “The Time.”

As is often the case with such legal entanglements, the narrative is more complicated than a few social media posts can contain, says Jonathan Steinsapir, an intellectual property lawyer with Kinsella Weitzman who represents clients including Michael Jackson’s estate.

“It’s a weird situation,” Steinsapir says. Whether Day is able to tour as he wants doesn’t only depend on a 1982 contract but on how Prince handled the arrangement over the years. Stressing that he hasn’t seen the contracts, Steinsapir says that if Day was continuously performing as Morris Day and the Time from the ’80s without Prince’s objection, Day might be able to claim that “Prince abandoned this contractual right — and the estate can’t revise things that Prince let go.”

According to concert tracking site Setlist.FM, the Time has performed every year since 1982; before the pandemic, Day and the Time had performed a few dozen concerts per year. But, continues Steinsapir, “if Prince was writing him a letter every year or every five years saying, ‘I know you’re doing this and you have my permission — but just remember all the trademark rights are still mine,’ then that would mean Prince was making sure that this was being done with his consent.” If so, the estate would have an easier case.

Entertainment attorney Erin Jacobson has read the estate’s letter to Day. She says that “in these types of arrangements, there is usually a license fee or royalty paid to the trademark owner in exchange for the ability to continue using the name. Therefore, there is opportunity for Day to continue to use the name, as long as he is not claiming ownership of the name.”

Steinsapir says Day’s issue with the Prince Estate is similar to one between the Jackson 5 and Motown that occurred after the band left the label in the mid-1970s. Motown claimed ownership of the trademark for “the Jackson 5.” Rather than go to court, the Jackson 5 became the Jacksons. Motown owner Universal Music Group, adds the attorney, “still enforces the trademark to this day.” Pulling up the file on his computer, he says, “It was filed in 2018. They’re still exploiting that so they can put it on products.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.