Daryl Hall on the ups and downs of duo-dom, his secrets to aging well and hating Jann Wenner

- Share via

The five solo albums Daryl Hall has released, starting with “Sacred Songs” in 1980, include two singles that landed in the Top 40. By comparison, Hall and John Oates have had 29 hit songs, making them the bestselling duo of all time — a fact Hall disputes, but more on that in a minute.

Solo albums from singers in hugely popular groups don’t always sell well — for every Phil Collins, there’s a Mick Jagger and a Scott Weiland. Fans seem to almost resent a singer who separates from their band, but also, singers sometimes use solo albums to restlessly explore offbeat sounds.

Hall, for example, has recorded with an array of musicians ranging from King Crimson guitarist Robert Fripp to Dave Stewart of Eurythmics and funk guitarist Wah Wah Watson. When he compiled the highlights of those albums for a new solo compilation, “BeforeAfter,” he selected songs specifically “so people would understand that my body of work consists of — hell, all kinds of things,” he said, calling from the kitchen of his London home.

The singer who made your mom’s favorite Christmas CD may not be cutting-edge, but he has Paul McCartney on speed dial and a newfound appreciation for life.

The 30 songs he compiled include eight from “Live From Daryl’s House,” a web series and TV show he started in 2007 from his home in upstate New York, where he and his band perform with guest stars, including Wyclef Jean, Sammy Hagar, Smokey Robinson, Cheap Trick and the O’Jays. One “Live From Daryl’s House” highlight is his duet with Todd Rundgren on “Can We Still Be Friends.” Hall and Rundgren recently announced a joint tour, starting April 1, which features separate sets from each, and then a few songs performed together.

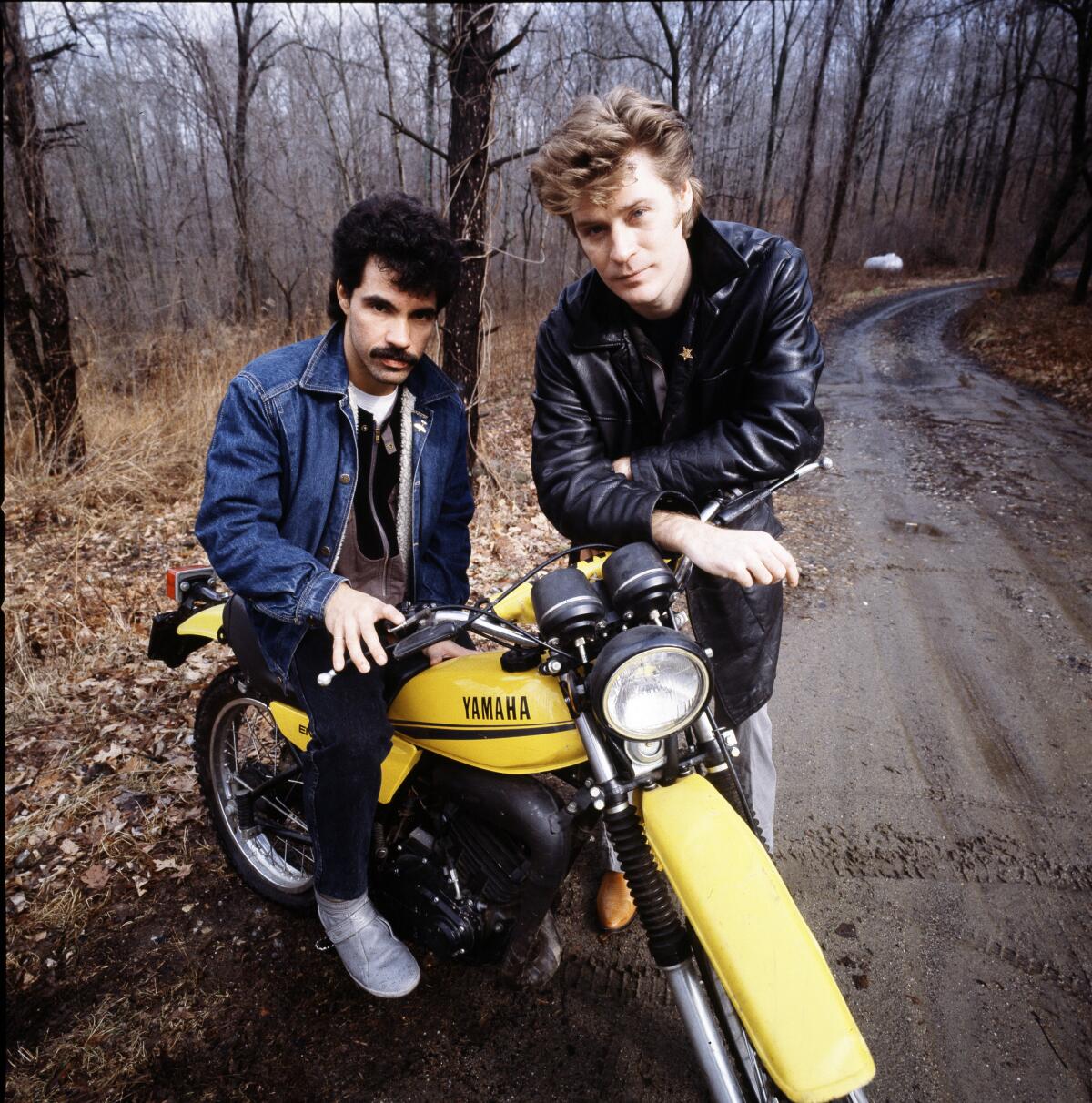

Daryl Franklin Hohl (he changed the spelling of his last name) grew up in Pottstown, just outside Philadelphia, at a time when the city was flowering into a hotbed of soul music. One Sunday afternoon, when he was performing at a local record hop, rival gangs began shooting at one another, and Hall and his group, the Temptones, hurried to a service elevator where he met John Oates, who was escaping with his group, the Masters. Hall and Oates became friends, then roommates, then bandmates.

Even over the phone, Hall’s self-confidence is palpable. He talked humorously but forcefully about being a young-looking 75-year-old, how he escaped being eaten by a jaguar and why it’s “quite annoying” to be part of a music duo.

While you were compiling “BeforeAfter,” you spent a lot of time with your solo records. Does your solo work have a different character than Hall & Oates?

It has to do with the people I worked with. And I worked with some pretty amazing people on those solo records, as I did with Hall & Oates records.

It’s not dissimilar to “Live From Daryl’s House.” It’s different collaborations and combinations of people, but I sort of hold it all. I’m the vortex. I’m in the middle, and it all revolves around me.

On your first solo album, “Sacred Songs” and “Something in 4/4 Time” got radio airplay. But I noticed on one streaming service that of all the songs on the album, the one with the most spins is “Babs and Babs,” an almost eight-minute song with no chorus. Does that surprise you?

[laughs] No, because it’s an interesting song. It’s not a pop song. None of my songs are — they’re just songs.

“Babs and Babs” is a series of verses. It was about the two sides of your brain, the creative side and the analytical side. Babs and Babs are the right and left lobes, and the song is about the brain talking to itself. I think my audience, especially the audience that likes “Sacred Songs,” appreciate the interesting factor, as opposed to the accessible factor.

Is there an alternate universe where, after you and Robert Fripp work on “Sacred Songs,” you become the singer in King Crimson?

There may be an alternate universe. I’ve been in contact with Robert — I’ve never really lost contact — and we’re talking about doing more stuff together, so hahaha.

What does the title, “BeforeAfter,” mean?

If you think about it, what is “before after”? It’s now. It also encompasses the fact that the things that happened before affect now, and the things that will happen in the future affect now.

When you were listening to your solo albums, were there songs that made you think, “I forgot how good this is”?

That happened a lot. I was just with Dave Stewart in the Bahamas, and we listened to [1986’s] “Right as Rain,” which is one of Dave’s favorites from “Three Hearts in the Happy Ending Machine,” which he co-produced. I’d forgotten how good the production is. And there’s so many songs I could say the same thing about. I guess not only was I on fire, but all the people I was working with were on fire.

Joni Mitchell sings an amazing harmony on “Right as Rain.” How did that come about?

I used to know Joni very well. When Dave and I make music, we laugh a lot. On that night, I found out Joni was in town, in London, and asked her to come to the studio and just fool around. She wound up playing drums and everybody was switching instruments. I can picture her singing those background vocals, waving her arms around with a beret on. It was really a magical evening.

When you do “Daryl’s House,” is there a song of yours that guests ask to sing most frequently?

A lot of artists want to play “Rich Girl” or “You Make My Dreams.” And I always say, “No, you’ve got to go deep. This show is not about the obvious; you have to delve into the catalog.” With “BeforeAfter,” I tried to showcase those songs.

Why aren’t there more duos in music? Is being in a duo harder than being in a group?

The truth is that most groups are duos. What are the Rolling Stones? Jagger and Richards. What’s the Who? Daltrey and Townshend. Lennon and McCartney is a little bit of a stretch, because George was in there — but if you watch the [“Get Back”] documentary, it was Lennon and McCartney. All duos. The most common thing in music is a creative partnership, especially one formed as kids, as a two of us against the world kind of thing.

So maybe Hall & Oates aren’t the bestselling duo of all time. Maybe it’s the Beatles.

I used to say that. People would say “You’re the bestselling duo of all time,” and I was like, “We’re just another band. You’ve given me the wrong appellation.”

A DJ and record-shop owner in downtown L.A. says that he’s being force to vacate his premises because of his Russian roots.

Is there a mystique about duos?

Whatever the mystique is, I don’t like it. John and I call our touring company Two-Headed Monster, because it is that. It’s very annoying to be a duo, because people always say, “Oh, you’re the tall one, you’re the short one. You’re the one that sings, you’re the one that doesn’t sing.” You’re always compared to the other person. It works with comedy entities, like Laurel and Hardy or Abbott and Costello, but with music, it’s f— up, actually.

In what way?

Everything you do is juxtaposed against another person. Try doing that sometime. I don’t want to use the word “emasculating,” because that’s male, but it takes away your individuality.

And people seem to speculate about duos in a way they don’t with bands. “Those two guys can’t possibly like one another.”

There you go. That’s an extension of what I’m talking about. “If they’re not working, they must be fighting.” It’s quite annoying.

When I looked up your age, I realized you and Donald Trump are both 75. How come you don’t look your age?

[laughs] I love it! I think about that all the time. I live right, man. I have the right headspace. If I was a fat, evil f— like him, I’d turn into Dorian Gray’s picture too.

My only advice is, have the right mother and father. My mom is 98. And my father died at 96, and he looked 66.

Even in your sad songs, there’s a quality in your voice that feels like optimism, or maybe resolve. Do you agree?

I know exactly what you mean. A Hall & Oates song like “She’s Gone” is the ultimate example. We’re almost jubilant. I’m shouting, “She’s gone!” and it sounds like it’s the greatest thing that ever happened. I’ve done that a lot in my songs. “Resolve” is a good way to put it.

My favorite Hall & Oates song is “Out of Touch.” In the verse, you sing “Soul really matters to me,” and in the second verse, you follow that with an ad lib, “Too much.” What’s the purpose of the ad lib?

Again, I was being ambiguous. “We’re soul alone and soul really matters to me. Too much.” Like, that can hurt. When you’re a sensitive, creative person, things are more intense. Both good and bad.

When Hall & Oates were on the cover of Rolling Stone in 1985, you were quoted as saying, “I’m just about the best singer I know” and you called Hall & Oates the Beatles of the 1980s. You later said you were misquoted. Did the article create any lasting damage to your reputation or image?

No. It created temporary damage, and f— [Rolling Stone founder] Jann Wenner and the horse he rode in on.

What was the temporary damage?

Just a perception of me and Oates, separately and together, as something we weren’t. Jann Wenner loved destroying careers. He’d pick somebody to knock down, and we wound up on the knockdown side for a while. But I prevailed, and the ending turned out a lot differently.

For instance, Wenner was one of the founders of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, which you and John were inducted into a few years ago.

We were reluctantly inducted. [laughs] I forgive, but I don’t forget.

You’ve said “Live From Daryl’s House” was inspired by the early days of MTV. But you didn’t enjoy making music videos in the ‘80s, did you?

We had a song called “Maneater,” and the director said, “Let’s bring in a jaguar.” They brought in a caged jaguar, and it was the evilest, nastiest thing I’ve ever seen. They drove a metal staple into the ground, put a wire on it, and attached the wire to the jaguar’s collar so it couldn’t do anything. Somebody f— up and the next thing we knew, it was running amok and people were screaming. It went up into the rafters of the studio we were using, and nobody knew how to get it down. I said, “F— this,” and left them with the jaguar.

It took them, I think, all night to get it down. They probably had to shoot it, I don’t know. That pretty much describes the MTV era of video making. Talk about excess, oh my God. [laughs] Of course, I paid for it all.

When will there be a new Daryl Hall and John Oates record?

Well, that’s inappropriate to this conversation. But I have no idea. I don’t have any plans to work with John. I mean, whatever. Time will tell.

That’s surprising. I’ve seen recent stories where you said the two of you were working on a record together.

That was before the pandemic. Perceptions changed, life changed, everything changed. I’m more interested in pursuing my own world. And so is John.

That takes me back to what I was saying about duos. I had to say, “And so is John.” I couldn’t just say what I think, I had to add what he thinks. That’s the f— up part of being a duo.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.