Here’s how Taylor Swift’s prolific run of albums stacks up against the all-time greats

- Share via

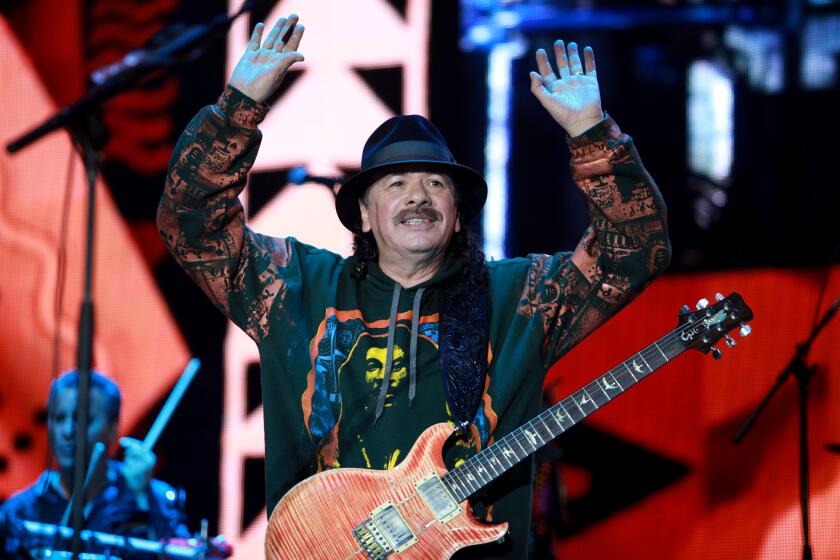

Taylor Swift is on a tear.

On Friday, the pop superstar is set to release her new album, “Midnights,” which she’s described as “a journey through terrors and sweet dreams” that features 13 tracks including a duet with Lana Del Rey. The LP will be the fourth set of new songs she’s dropped since 2019, when “Lover” came out and was quickly followed by a pair of 2020 albums, “Folklore” and “Evermore,” that the singer recorded during the COVID pandemic; last year she added to the pile with the first two installments, “Fearless (Taylor’s Version)” and “Red (Taylor’s Version),” in her plan to re-record the six albums that partially slipped out of her control when her old record label changed hands. Each of these projects debuted at No. 1; “Folklore” topped many critics’ best-of-2020 lists, while “Red’s” 10-minute version of “All Too Well” set the take-o-sphere ablaze.

Swift’s combination of prolificacy and commercial success is exceedingly rare these days, when the lucrative payoff of a global arena or stadium tour offers little incentive to shorten the life of a hit album by issuing another one too soon. (Without COVID’s disruption of live music, it’s unlikely that Swift would’ve returned to the studio when she did.) But this kind of hot hand is not unheard of in musical history: Just look at some of the great singer-songwriters of the 1970s, which is the creative model that Swift appears to be operating by at the moment.

A half-century ago, the LP became the dominant mode of pop expression, in part because it offered musicians a tantalizing palette and in part because those shiny black discs were profitable as hell. Careers were built with album-length statements, not with bite-size tweets and TikToks; audiences were trained to scour vinyl platters not just for hits but for meaning. And because time moved more slowly, artists could paradoxically move with speed without seeming to be in a rush — at least until we realize in retrospect that Aretha Franklin dropped “Amazing Grace” and “Young, Gifted and Black” in the same year.

Taylor Swift’s 10th studio album ‘Midnights’ boasts 13 tracks, including one about boyfriend Joe Alwyn, a collab with Lana Del Rey and her favorite song she’s written.

So as we wait for Swift’s latest, here’s a look back at some of those earlier hot streaks, divided into groups of increasing perfection and with the caveat that only solo artists (not bands) working in the ’70s were considered. The criteria for inclusion was at least four classic or near-classic albums in at most five years, which is why some of the decade’s giants — Marvin Gaye, for instance, and Paul Simon — didn’t make the cut.

NEAR-GENIUS

Billy Joel

“Turnstiles” (1976)

“The Stranger” (1977)

“52nd Street” (1978)

“Glass Houses” (1980)

Joel told The Times in 2017 that his fourth solo studio album was the one that made him believe, after a decade of trying, that “maybe I could do this — maybe I am a recording artist.” Duly convinced, he quickly followed “Turnstiles” by teaming with producer Phil Ramone for the three chart-scaling LPs on which his legend is built. “The Stranger” blended the tough-guy bluster of “Movin’ Out (Anthony’s Song)” with the shameless sentimentality of “Just the Way You Are,” which won Grammys for record and song of the year; “52nd Street” took album of the year at the next Grammys ceremony thanks in part to the muso explorations of songs like “Zanzibar,” which found new life not long ago among the kids on TikTok. By “Glass Houses,” Joel was eager to prove he could rock as hard as the new wavers nipping at his heels — a chip on his shoulder that drove him to his first No. 1 pop hit in “It’s Still Rock and Roll to Me.”

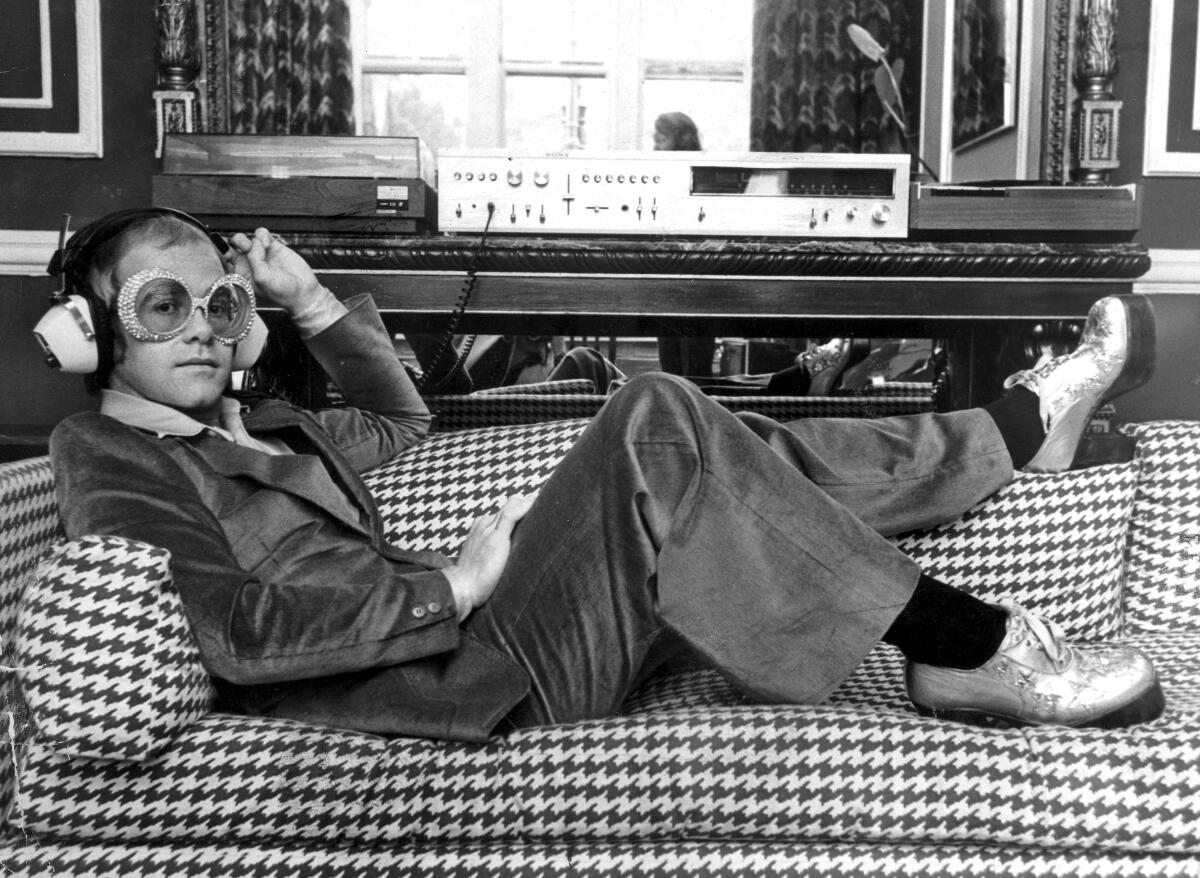

Elton John

“Madman Across the Water” (1971)

“Honky Chateau” (1972)

“Don’t Shoot Me I’m Only the Piano Player” (1973)

“Goodbye Yellow Brick Road” (1973)

“Caribou” (1974)

“Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt Cowboy” (1975)

“Rock of the Westies” (1975)

John was pop’s greatest singles act of the ’70s, which means his true hot streak was the three-year span between “Elton John’s Greatest Hits” in 1974 and “Elton John’s Greatest Hits Volume II” in 1977. (Leave it to his future frenemy Joel to drop two volumes at once in 1985.) But even with loads of filler surrounding the indelible hits — and even accounting for the fact that Bernie Taupin was handling the lyrics — John’s albums from the first half of the decade constitute a wild burst of tune-making in as many styles as he could seemingly think up, including but not limited to soft rock, hard rock, country-rock, glam rock, soul-rock and, oh yeah, “Crocodile Rock.”

Paul McCartney

“McCartney” (1970)

“Ram” (1971)

“Wild Life” (1971)

“Red Rose Speedway” (1973)

“Band on the Run” (1973)

The Cute One began his post-Beatles career with what seemed at the time like a lark. Yet the intervening half-century has recast the quirky-scrappy “McCartney” as a landmark in DIY pop; ditto “Ram,” the shaggy and bucolic duo album he and his wife Linda released just 13 months later. (Upon “Ram’s” release, Robert Christgau described the album’s lead single, “Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey,” as “a major annoyance”; Pitchfork, in a review of a 2012 reissue, said it’s “clearly one of McCartney’s five greatest solo songs.”) Paul and Linda then formed Wings with Denny Laine of the Moody Blues and started busting out rapid-fire LPs whose determined informality — “Wild Life” opens with tunes called “Mumbo” and, uh, “Bip Bop” — couldn’t conceal the undimmed songwriter’s flair at work in tunes as varied as the zippy “Jet,” the lushly devotional “My Love” and the epic-in-five-minutes “Band on the Run.”

Dolly Parton

“Coat of Many Colors” (1971)

“My Favorite Songwriter, Porter Wagoner” (1972)

“My Tennessee Mountain Home” (1973)

“Jolene” (1974)

Years before she became a down-home Hollywood fixture — but well after she’d established herself as a talented Nashville songwriter and duet partner — Parton made a couple of highly personal country albums based on her hardscrabble upbringing in the Great Smoky Mountains. Yet neither “Coat of Many Colors” nor “My Tennessee Mountain Home” forsakes writerly imagination for the sake of diaristic realism — see the former’s frisky “Traveling Man,” about a love triangle between a mother, a daughter and the busy salesman who keeps knocking on their door. “My Favorite Songwriter, Porter Wagoner” showcased the gentle ebullience of Parton’s singing ahead of her messy split from the creative foil who helped make her a star; the Wagoner-inspired “I Will Always Love You,” one of two endlessly covered pop classics from the sumptuous “Jolene” album, achieves a profound mixture of regret, longing and gratitude.

GENIUS

Elvis Costello

“My Aim Is True” (1977)

“This Year’s Model” (1978)

“Armed Forces” (1979)

“Get Happy!!” (1980)

Anger — fueled by the cruelty of politics, by the indignities of capitalism, by Costello’s somewhat creepy ideas about women — was no impediment to productivity as punk’s smarty-pants polemicist banged out the nearly five dozen songs found on his first four studio albums. Nor did his big feelings obscure his editor’s eye: More than their pungent wordplay or their supremely catchy hooks — the latter handled by the Bay Area country-rock act Clover before Costello convened his stalwart Attractions — what impresses now about these early LPs is how wound-tight they are.

Aretha Franklin

“Spirit in the Dark” (1970)

“Live at Fillmore West” (1971)

“Young, Gifted and Black” (1972)

“Amazing Grace” (1972)

Assuredly ensconced as the Queen of Soul, Franklin looked back to her gospel roots as the ’70s began for the stirring “Spirit in the Dark” and “Amazing Grace,” the astounding double live LP she recorded over two performances at Watts’ New Temple Missionary Baptist Church filmed by director Sydney Pollack (whose documentary footage then sat in a vault until Franklin’s family finally blessed its release not long after the star’s death in 2018). The singing on “Amazing Grace” — widely believed to be the bestselling live gospel album of all time — can still blow your hair back; it’s deeply moving too to hear how naturally Franklin resumes her place in a synergistic choral setting. Yet her return to the church didn’t keep her from chasing more Earthly inspirations: Between “Spirit” and “Grace” came “Live at Fillmore West,” with wildly funky concert renditions of tunes by the Beatles and Bread (!), and “Young, Gifted and Black,” on which she cuts a rug in “Rock Steady” and uses Nina Simone’s title cut to ponder the importance of self-belief in a poisoned world.

Bob Marley

The Wailers, “Catch a Fire” (1973)

The Wailers, “Burnin’” (1973)

“Natty Dread” (1974)

“Live!” (1975)

Reggae’s first superstar had help from his longtime bandmates Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer in taking Jamaican music to the rest of the world with the Wailers’ pair of head-turning 1973 LPs. But Marley continued to thrive even after Tosh and Wailer left (and Eric Clapton turned “I Shot the Sheriff” into a global smash); he’s as convincing on “Natty Dread” dispensing sweet reassurances as he is warning government officials about the motivating power of hunger. Expertly recorded in London using the Rolling Stones’ gear, “Live!” presents highlights from the three earlier albums, including a smoldering “No Woman, No Cry” in which you can practically hear the audience swaying to the unhurried groove.

Neil Young

“After the Gold Rush” (1970)

“Harvest” (1972)

“Time Fades Away” (1973)

“On the Beach” (1974)

“Tonight’s the Night” (1975)

The title of “After the Gold Rush” might’ve suggested that Young — by then a ’60s-rock hero thanks to his work with Buffalo Springfield and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young — had already had enough of pop stardom. But true celebrity only arrived with the mellow country-rock stylings of “Harvest,” which in addition to backing vocals by C, S and N featured cameos from James Taylor, Linda Ronstadt and the London Symphony Orchestra — certainly one way to spend a bit of cultural capital. Young’s response to “Harvest’s” huge success was the beautifully ragged “Ditch Trilogy,” so named because of where he said he was aiming to get out of: the middle of the road.

After a week in which West promoted antisemitism and white supremacy, his business partners, from Adidas to Def Jam, may be distancing themselves from the star.

SUPERGENIUS

David Bowie

“Hunky Dory” (1971)

“The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars” (1972)

“Aladdin Sane” (1973)

“Young Americans” (1975)

“Station to Station” (1976)

Bowie’s interest in persona casts such a long shadow over modern pop that it can feel like he spent ages performing as each of his carefully devised alter egos. In fact, he cycled through styles and identities with astonishing speed, moving in a mere five years from the frilly cabaret pop of “Hunky Dory” through the feverish glam of “Ziggy Stardust” and “Aladdin Sane” and the so-called plastic soul of “Young Americans” before remaking himself yet again as the Thin White Duke with the spacey and forbidding “Station to Station.”

Brian Eno

“Here Come the Warm Jets” (1974)

“Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy)” (1974)

“Another Green World” (1975)

“Before and After Science” (1977)

“Ambient 1: Music for Airports” (1978)

A crucial studio partner to Bowie during Bowie’s late-’70s stint in Berlin, Eno had his own hot streak as an artist earlier in the decade, pumping out lovably deranged pop records as though he were following up on every out-there impulse he’d had while playing in Roxy Music with the comparatively straitlaced Bryan Ferry. Sometimes he’s so eager to try out every sound he can think of — here a vinegary guitar riff, there a burbling synthesizer — that the music can evoke two records spinning at the same time. No wonder, then, that between his solo work and his many production jobs, Eno helped invent ambient music with the radically calming “Music for Airports.”

Al Green

“Al Green Gets Next to You” (1971)

“Let’s Stay Together” (1972)

“I’m Still in Love With You” (1972)

“Call Me” (1973)

The most consistent soul singer in music history, Green got in the pocket in the early ’70s and simply never got out. His partnership with producer Willie Mitchell — who put Green’s honeyed growl over an elegant bed of slinky guitar, heartbeat bass, creamy organ and horns that punched like velvet hammers — made for an instantly recognizable sound even as Green ventured beyond his own meditations on love and happiness to cover tunes by Roy Orbison, Hank Williams and the Bee Gees. You could play these four albums in a row and never once change the tempo at which you’re rocking your shoulders. But the emotional journey you’ll have been on with Green — the tastes of ecstasy and the glimpses of desperation — will leave you happily spent.

Joni Mitchell

“Ladies of the Canyon” (1970)

“Blue” (1971)

“For the Roses” (1972)

“Court and Spark” (1974)

“The Hissing of Summer Lawns” (1975)

Mitchell’s vaunted position as the patron saint of confessional songwriting has much to do with the devastating “Blue,” which topped NPR’s recent list of the 150 greatest albums made by women and which came in at No. 3 on the latest edition of Rolling Stone’s rundown of the 500 greatest albums of all time. But Mitchell was already humming by the time she began her masterpiece — “Ladies of the Canyon,” which came out when she was in her mid-20s, is remarkably wise about work and motherhood — and she stayed in the zone for “Blue’s” two follow-ups, which broaden her folky singer-songwriter sound with slinky jazz-pop arrangements as sophisticated as her lyrics. Having reached a career-best No. 2 on the Billboard 200 with “Court and Spark,” Mitchell went arty-experimental with “The Hissing of Summer Lawns,” rightfully confident that her audience — not to mention other onetime guitar-strummers — would catch up eventually.

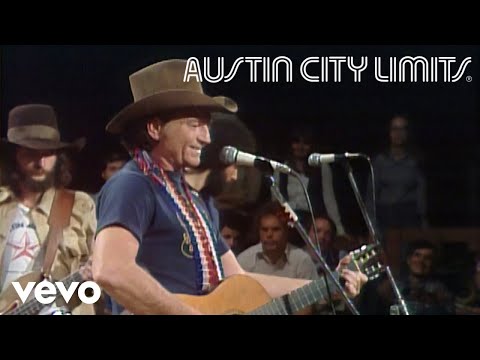

Willie Nelson

“Shotgun Willie” (1973)

“Phases and Stages” (1974)

“Red Headed Stranger” (1975)

“To Lefty from Willie” (1977)

“Stardust” (1978)

Hard-wired to build meaning and emotion into country songs of two or three minutes, Nelson expanded his thinking in the mid-’70s with the string of concept albums he made after leaving Nashville for Austin and quitting RCA Records for the more permissive Atlantic and Columbia labels. “Shotgun Willie” is a simmering country-soul collab with producer (and Atlantic exec) Jerry Wexler, who stuck around for “Phases and Stages,” on which Nelson tells the story of a couple’s divorce — both her version and his — over two sides of an LP. The gorgeously stripped-down “Red Headed Stranger,” about a murderous preacher, earned Nelson his first No. 1 album. Then came his loving tribute to country pioneer Lefty Frizzell, followed by “Stardust,” the surprise-blockbuster standards collection that showed this master songwriter was also one of pop’s great interpreters.

GODHEAD

Stevie Wonder

“Music of My Mind” (1972)

“Talking Book” (1972)

“Innervisions” (1973)

“Fulfillingness’ First Finale” (1974)

“Songs in the Key of Life” (1976)

Wonder’s miraculous mid-’70s run is why artists still dream about the idea of complete creative control: Re-upped with Motown, as the story goes, on a contract that guaranteed no suit would second-guess him, the former child prodigy set about pushing his music as far as he could envision, not just in terms of its technological innovations — think of these albums as a virtual library of synthesizer textures — but in its determination to consider romantic contentment as part of a broader sociopolitical system. Wonder’s trick, of course, was that he paired those high-minded advances with a melodic and rhythmic sense that also seemed to be growing — seemed to be doubling, really — by the year. If songs as exuberant as “Sir Duke,” “Living for the City” and “You Are the Sunshine of My Life” somehow don’t convince you that Wonder was tapped into something real, consider that no other artist has won Grammys for album of the year with three consecutive LPs as Wonder did with “Innervisions,” “Fullfillingness’ First Finale” and “Songs in the Key of Life.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.