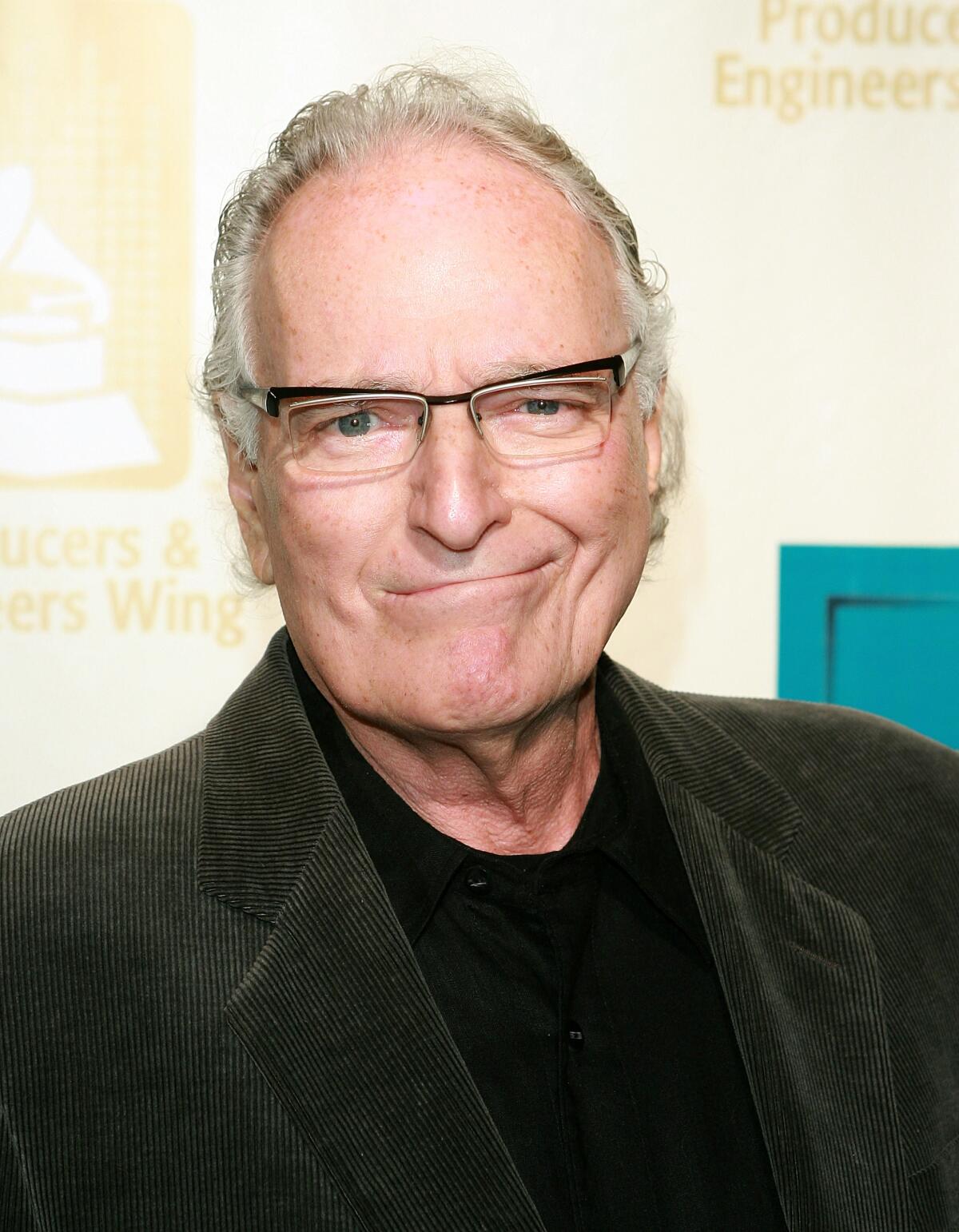

Jerry Moss, the ‘M’ of A&M Records, dies at 88

- Share via

Jerry Moss, the record executive who was the “M” in the seminal West Coast label A&M Records, has died. He was 88.

His death was announced Wednesday by his family. “Our, husband, father, grandfather/great grandfather and friend died peacefully ... in his home in Bel Air, CA,” the statement read.

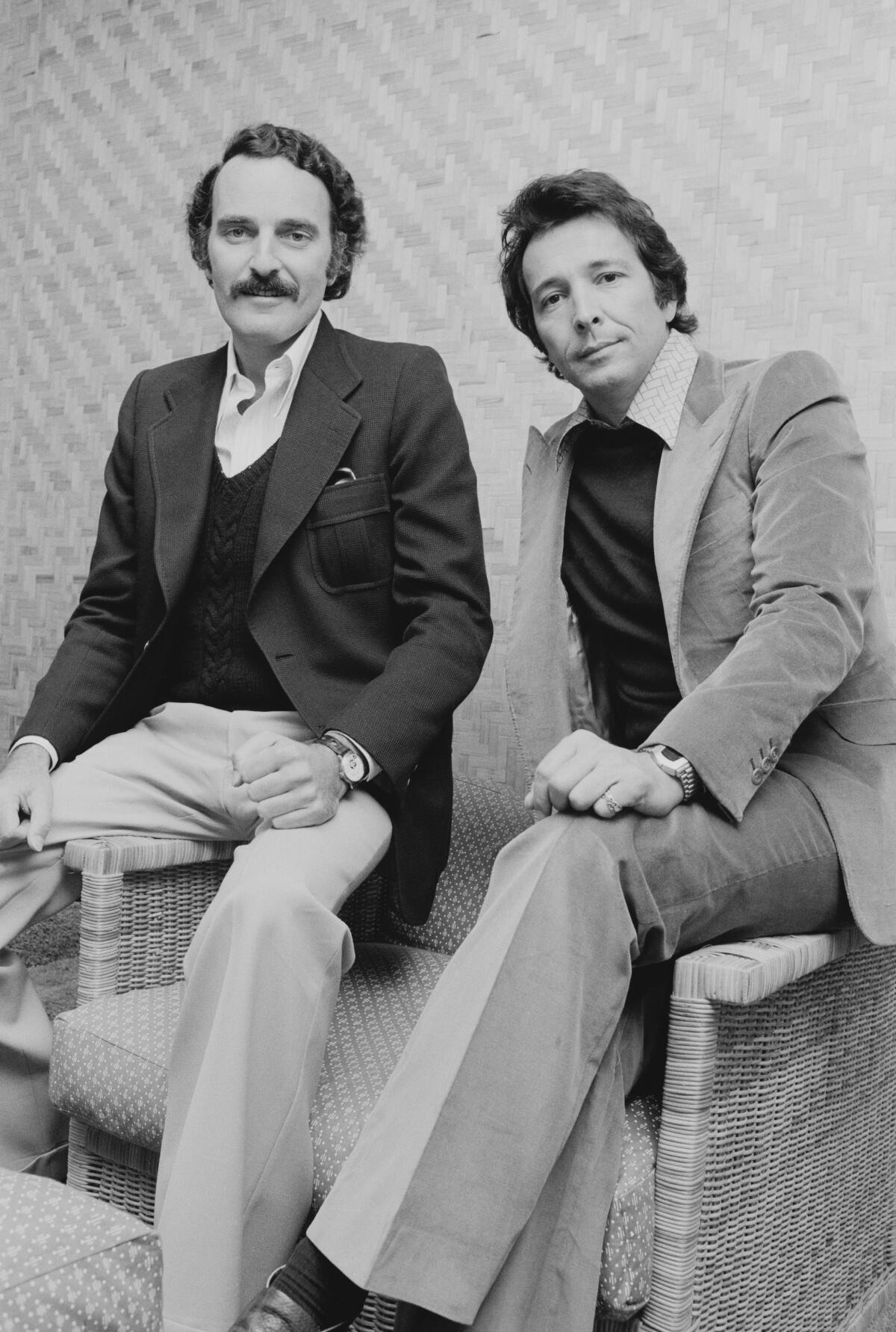

A&M, the label Moss co-founded in 1962 with trumpeter and bandleader Herb Alpert, was home to many of the bestselling acts of the rock era, including the Carpenters, Cat Stevens, Joe Cocker, the Police, Styx, Peter Frampton and Soundgarden. Such success was the byproduct of A&M being designed as a safe haven for artists, a label that built careers by allowing musicians to take risks.

Moss was central to cultivating that reputation, helping to transform A&M from an easy-listening label to a serious force in album-oriented rock ’n’ roll. Cultivating connections with British record labels and expanding his A&R staff, Moss set A&M on a path that led to such era-defining albums as 1976’s mega-selling double LP “Frampton Comes Alive!”

It wasn’t the only time Moss adapted to fit the times. He helped reshape A&M’s roster in the late 1970s, bringing in new wave acts the Police and Joe Jackson while also finding space for the modern R&B of Janet Jackson.

Alpert and Moss sold A&M to Polygram in 1989 for a reported $500 million. They remained at the label but clashed with Polygram management and left in 1993.

In 1994, they formed a new label, Almo Sounds, releasing albums by Garbage, Ozomatli and Gillian Welch over the course of five years.

Moss and Alpert were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2006 as nonperformers.

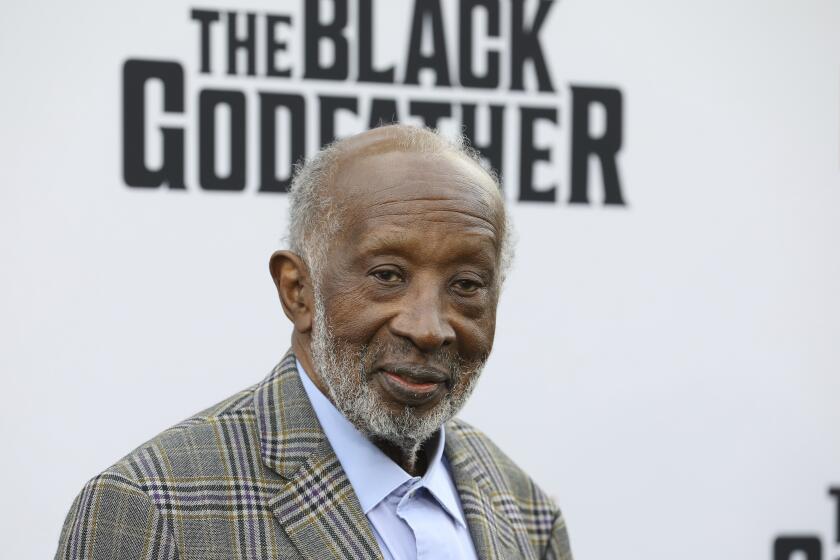

‘Black Godfather’ director Reginald Hudlin on Clarence Avant: ‘His effect is literally immeasurable’

Reginald Hudlin, director of Netflix’s Clarence Avant documentary ‘The Black Godfather,’ on Avant’s legacy, political impact and imprint on Hollywood.

In 2020, Moss and his wife, Tina, gave $25 million to the Music Center, the largest gift earmarked for programming in the organization’s history.

The Music Center plaza that links the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, the Mark Taper Forum and the Ahmanson Theatre was named Jerry Moss Plaza.

“I consider myself a music man, and I would like to celebrate that at this stage of my life,” Moss said at the time.

Moss’ life was celebrated earlier this year at a tribute concert held at the Mark Taper Forum that featured appearances by Alpert, Frampton, Sting, Rita Coolidge and Amy Grant.

At the concert, reported Billboard, tributes flowed freely. Alpert said, “To be honest, I don’t think I would have had the musical career without Jerry Moss,” a sentiment echoed by Frampton: “Thank you, Jerry Moss, for my entire career.” Sting called Moss “an elder brother, a wise head, a man’s man and a mensch.”

For the record:

12:17 p.m. Aug. 18, 2023An earlier version of this obituary incorrectly said Moss came of age during the Great Depression.

Jerome Sheldon Moss was born in the Bronx, N.Y., on May 8, 1935. A graduate of Brooklyn College, Moss served in the Army prior to beginning his career in the music business. Hired by Coed Records to promote “16 Candles,” a dreamy doo-wop ballad by the Crests, Moss helped get the record onto the charts; it reached No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1959.

The success of “16 Candles” inspired Moss to move to Los Angeles in 1960. He spent a couple years working as an independent promoter and producer, running in circles that eventually led him to meet Alpert. Fresh from a severed partnership with Lou Adler, Alpert was eager to get into business with Moss. The two sealed their partnership with a handshake and a $100 stake in their own independent record label.

Calling their new venture Carnival Records, the pair released “Tell It to the Birds,” a pop trifle credited to “Dore Alpert” that received some airplay in Los Angeles in 1962. Shortly after its release, the pair learned of another label of the same name, so they renamed their venture A&M Records. The first single released under the A&M banner was Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass’ “The Lonely Bull,” a jazz instrumental with a mariachi flair that became a national hit, reaching No. 6 on Billboard’s Hot 100 in 1962.

After the quick start, A&M settled into the workaday business of an indie label, balancing Alpert releases with singles primarily aimed at jazz and pop markets, although they did also release early works by Waylon Jennings, Leon Russell and Terry Stafford. A&M didn’t have another significant success until 1965, when Alpert embraced pop on “Whipped Cream & Other Delights,” an album as famous for its provocative album cover depicting a model slathered in whipped cream as it was for its swinging rendition of “A Taste of Honey.” “Whipped Cream & Other Delights” started a remarkable streak of five No. 1 albums for Alpert, hits that turned the label into a powerhouse.

He’s the first African artist to sell out an American stadium. Now, with a new album steeped in hip-hop, Burna Boy has his sights set on something even bigger.

In the wake of “Whipped Cream,” A&M moved its operations from a garage to the Charlie Chaplin Studios on La Brea Avenue. They kept their aim firmly on the pop mainstream, having hits with Sergio Mendes & Brasil ’66 — an act that sounded uncannily like the Tijuana Brass — while targeting younger listeners with the folk-rock outfit We Five (“You Were on My Mind”) and Boyce and Hart, who graduated from Monkees songwriters to pop stars with “I Wonder What She’s Doing Tonight.”

Moss recognized that, while successful, these records were decidedly un-hip, a realization underscored by his attendance at 1967’s landmark Monterey International Pop Festival, featuring rock acts from Jimi Hendrix to Janis Joplin. In 2010, he recalled: “There was all this great music and new talent out there, and I was embarrassed we hadn’t signed any of them.”’

While A&M didn’t abandon mainstream pop — one of its biggest acts in the 1970s was the easy-listening duo the Carpenters — the label did start to build an adventurous roster starting with the Flying Burrito Brothers, the pioneering country-rock band fronted by former Byrds members Chris Hillman and Gram Parsons. Moss said later, “The Burritos really touched me. They set a course for us in America, that we were open and available and competitive in this area.” Although the Flying Burrito Brothers didn’t have commercial success, they did signal to other artists that A&M was no longer solely about middle-of-the-road pop.

Soon, A&M’s roster was filled with rock artists, many of whom hailed from England, such as Joe Cocker and Humble Pie, the blues-rock band from former Small Faces singer Steve Marriott. As A&M cultivated this album-oriented rock roster, it also signed a distribution deal with Ode Records, an imprint headed by Alpert’s one-time partner Adler, an arrangement that hit pay dirt when Carole King’s “Tapestry” became one of the biggest-selling albums of the 1970s.

“Tapestry” was joined on that list by “Frampton Comes Alive!,” a live double LP from the former Humble Pie guitarist. Top-sellers Styx and Supertramp also kept A&M on rock radio into the 1980s, but the label didn’t limit itself to any one genre; it also released R&B from Billy Preston, jazz from Chuck Mangione and records from Quincy Jones that bridged the two styles.

A&M embraced the rise of new wave in the late 1970s and early 1980s, signing such acts as the Police, Squeeze and Joe Jackson. The label buttressed its connection with the rock underground by signing a distribution deal with I.R.S. Records, an arrangement that brought the company the Go-Go’s, R.E.M., the English Beat and Fine Young Cannibals. A&M also inked deals with the new age imprint Windham Hill and released pop-oriented records from Amy Grant, the biggest act on the Christian label Myrrh.

A&M’s biggest hits during the 1980s belonged to Sting, either on his own or with the Police, and Janet Jackson, whose “Control” and “Rhythm Nation 1814” albums changed the course of R&B music and elevated her to a level of stardom comparable to her brother Michael.

Despite this success, Moss and Alpert recognized that the music industry was changing, with international corporations muscling out independent outfits like theirs. In 1989, they sold A&M to the Dutch company PolyGram. They remained on as A&M’s top executives, but this arrangement swiftly soured, and Moss and Alpert left the company in 1993. The pair sued PolyGram in 1998, claiming a breach of the integrity clause; they would settle the case for $200 million.

The documentary on Paramount+ looks at the 1968 TV special that reinvigorated Elvis Presley’s career with interviews from the director and others about the making of the show.

Not long after leaving PolyGram, Moss was diagnosed with prostate cancer. Once given a clean bill of health, he and Alpert launched a new label, Almo Sounds, which primarily specialized in alternative rock; their greatest success was with the Scottish American band Garbage.

An art collector who owned pieces by Magritte, Picasso, Warhol and Basquiat, Moss cultivated many interests outside music. Chief among these was horse racing and breeding. Named to the California Horse Racing Board in 2004, Moss owned Giacomo, a horse named after Sting’s son that won the 2005 Kentucky Derby.

Moss was also active as a philanthropist. He established the Moss Scholars program at UCLA in 2004 and was a founding trustee of the Geffen Playhouse.

Moss is survived by his wife of eight years, Tina; four children — Ron, Jennifer, Harrison and Daniela; five grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.