Arts journalists have a Twitter problem

- Share via

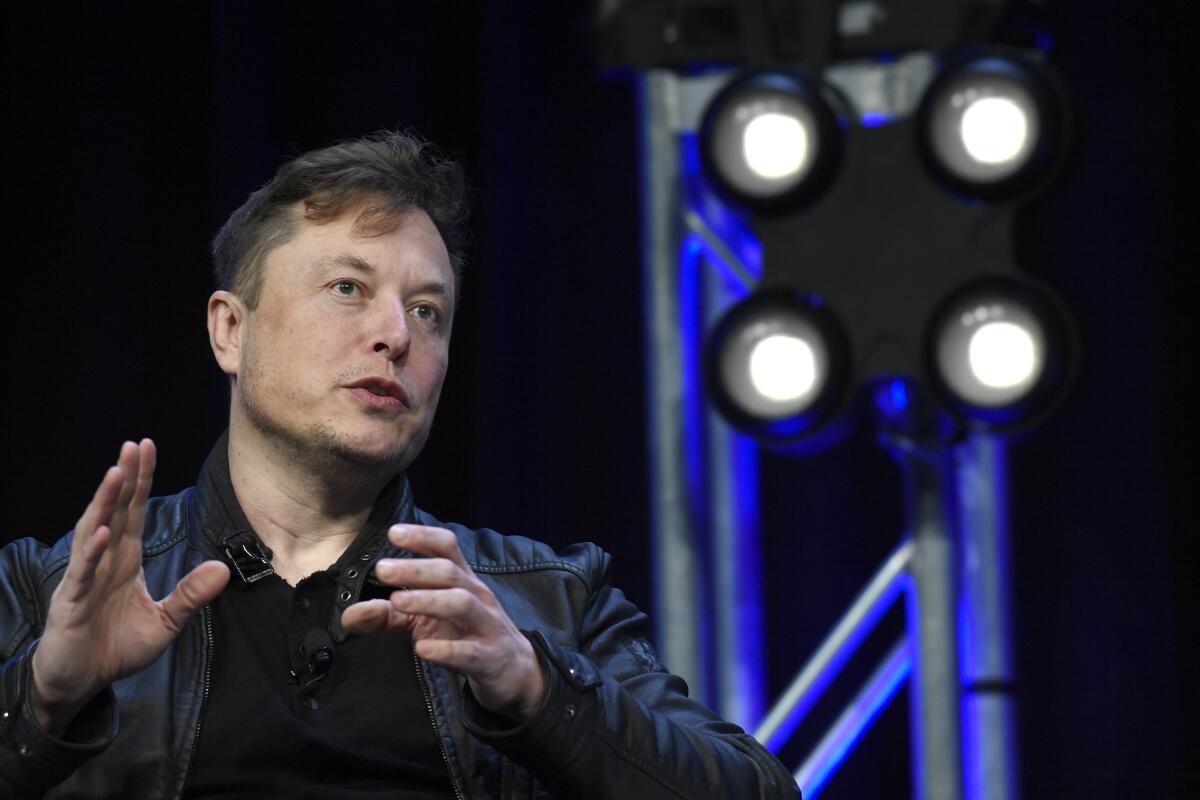

It’s Saturday morning and I’ve been up all night scrolling Twitter, trying to decide if my mandate as an arts and culture writer is in direct conflict with the use of the increasingly divisive social media platform under the new ownership of the world’s richest and most annoying man, Elon Musk. My job is to shine light on the ways that human creativity can illuminate, challenge and ultimately transform life on Earth, and to dig up injustice of all kinds as it relates to the creation, use and consumption of that art. Twitter’s job is to foment outsized outrage at just about everything.

I may love the latest COVID-inspired verse by @plaguepoems, and I always enjoy the faux-right-wing virility of @walterowensgrpa, whose bio reads: “Obamacare made my grandson gay Owen is my grandson I am his grandpa,” but is it OK for me to contribute to the success of a site that has become so ugly? The punk rocker in me loves a good dumpster fire, so my account remains active today. We’ll see what fresh horror tomorrow brings, and if I have the stomach for it.

I’m Twitter apologist Jessica Gelt filling in for Twitter aficionado Carolina A. Miranda, whose ability to wring pathos and humor out of 280 characters is truly epic — and I’ve got your essential arts news right here.

Journalism’s Twitter problem

Twitter is more than a cesspool of racist rantings, political infighting, cute cat memes and uncensored opinions that you wish you hadn’t seen — it’s also a news platform, made so by some of its most dedicated users: journalists.

According to a recent Pew Research study, Twitter is the most-used social media platform among journalists, with 69% of us saying that we use it the most, or second most, in the course of our jobs. (Guilty!)

We didn’t become addicts out of the blue: Twitter’s rise in the mid-aughts directly coincided with the devastating fall of print media.

The platform’s ability to drive traffic online was seen as a life raft for publications struggling to monetize the web. Twitter encouraged our ardor, and in those early days, entire newsrooms were given the coveted blue check marks denoting official accounts. We repaid the volatile social media site with our near-constant attention. I was once pulled into an editor’s office and reprimanded for not tweeting enough. He had been keeping track, it turned out — a practice not uncommon in newsrooms at the time.

When I ponder the role Twitter plays in society, I invariably think of Shirley Jackson’s 1948 short story “The Lottery.” The chilling tale depicts a small town’s practice of picking a citizen at random and stoning that person to death in the town square. As a parable about the dangers of mob mentality, “The Lottery” is without rival.

As a modern digital town square, Twitter is ruled by crowd psychology and prone to online stonings of all kinds. Twitter pile-ons can target relatively benign offenders like “Bean Dad,” whose thread about his 9-year-old daughter’s trouble opening a can of beans led to condemnation so severe that he was forced to deactivate his account and issue a public apology. In its most extreme form, it can spill out of the digital realm into real life, as the world saw in terrifying detail on Jan. 6 after President Trump tweeted, “Be there, will be wild!” to participants in the Capitol attack.

The site’s greatest failing is now being exacerbated by the platform’s new overlord: rock-thrower-in-chief and billionaire apostate, Elon Musk, who seems intent on offending almost everyone, recently tweeting, “Being attacked by both right & left simultaneously is a good sign,” and pinning to his profile a poll that asks what advertisers should value more, freedom of speech or political correctness.

Musk has also caused a furor by threatening to charge $8 per month for Twitter Blue, which verifies celebrity accounts, as well as those of most mainstream journalists. A revolt is in the making — with all kinds of well-known people, including master of horror Stephen King, declaring they will never pay for their blue check mark. Should identity verification vanish, the trolls will be empowered in formerly unimaginable ways.

This is all coming from a man who sees no problem reinstating the hate-mongering Trump’s Twitter account and could soon do so, and who recently posted, then deleted, a tweet linking to conspiracy theories about the violent attack on Paul Pelosi.

Musk’s ownership has pushed journalists who promote their work on the site to a moral crossroads: to tweet or not to tweet. For arts and culture writers, whose stories often don’t garner the broad readership enjoyed by big-tent entertainment news about Hollywood and pop music, Twitter has been an especially useful tool of dissemination. It’s a forum for meeting kindred spirits and fellow arts practitioners and for staying up to date on cultural conversations before they begin to trend.

Leaving is hard, although some journalists are already doing it. I applaud their resolve and ability to place principle above the convenient expediency of the fast-moving, ever-churning social media site. As I mentioned up top, I remain a Twitter user. One of my biggest concerns about society today is its extreme fracture, which I believe stems from our ability to silo ourselves off from ideas and people we find offensive and uncomfortable. For that reason I have never blocked someone on social media — no matter how angry or indignant they make me. And that’s how I’m justifying my continued presence on the site. It’s a window into the soul of America, and like America, it is exceedingly dark right now.

Below are where other members of Team Arts fall when it comes to that question. Answers are lightly edited and condensed for clarity and brevity:

Carolina A. Miranda: I’ve historically loved Twitter as a platform since, of all the social media spaces, it’s the one that I think best plays to writers — the tight confines of space making for a certain pithiness. And when I was a freelancer, it was my journalism water cooler. But it was getting increasingly toxic (well before Elon Musk), and I have deleted the app from my phone. (Do I need to wake up on Sunday to find some mansplainer with 10 followers informing me I’m an idiot? No gracias.) I’m hoping we can all act like it’s the late aughts and reunite on Tumblr. I still have an active account.

Mark Swed: Between 1965 and 1982, John Cage kept an irregular diary comprised of elliptical observations that read like proto-tweets. “Asked the Spanish doctor what she thought about the human mind in a world of computers,” began one. “She said computers are always right, but life isn’t about being right.” When he published the collection, he titled it: “How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse).”

Charles McNulty: Professional obligation brought me to Twitter and professional duty kept me there. Until, that is, Elon Musk, Twitter’s new owner, promulgated a link to a vicious conspiracy theory about the brutal attack on Paul Pelosi. My exit wasn’t dramatic. I changed my password to something I’d never be able to remember, signed out of my account, and the rest has been blessed silence.

Disgust with Musk’s irresponsibility aside, I’d been looking for a reason to say goodbye. Twitter was the first thing I would check when I opened my laptop in the morning. Under the illusion of keeping up, I found myself in a continual state of political outrage, wondering what fresh hell was in store for us this hour.

Attention is a limited resource, and as a writer I felt I was being prodigal with mine. There’s a world elsewhere — books, newspapers, websites and the replenishing art of human conversation. I feel no need to proselytize. My decision was personal. I wanted a longer view than a treadmill of 140 characters could provide.

Deborah Vankin: I loathe Twitter. There, I said it. I begrudgingly check it daily, several times a day (an hour?), to keep up on “the conversations”; but I consume it as a news feed rather than a platform for personal expression. Or as a space to promote recent stories. As a journalist, as an observer of our culture, the world, I feel an obligation to stay and monitor the site, what’s said, the good, the bad and the increasingly ugly. Leaving Twitter, taking a stand, is admirable; I understand the perspective. But as an objective journalist, I feel a greater obligation to stand in the midst of the chaos, to continue to observe and interpret, wherever that may lead. Especially because of where it may lead.

Steven Vargas: I have a love-hate relationship with Twitter. The app keeps me informed on what conversations are happening globally and locally. Although I’m able to keep up with the trends and memes, it’s also a source of anxiety. At some point, the information gets overwhelming, and the voices become repetitive. It’s particularly harmful when I witness injustices on my timeline, especially ones that hit close to home. It’s hard to look away, much less speak on the matter, yet there are many who have the ability to post without experiencing the pain of typing each character — whether it be from bravery or privilege. For this reason, I use the app in spurts, ensuring I don’t get caught up in the storm while still staying informed. The space can be toxic, but it can also be communal. It’s a balance I’m still navigating.

Make the most of L.A.

Get our guide to events and happenings in the SoCal arts scene. In your inbox every Monday and Friday morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

LA Vanguardia

The Times has published its exciting, illuminating and long-overdue LA Vanguardia project, which highlights “the Latino innovators, instigators and power players breaking through barriers.”

Many of its subjects are artists, including the Colombian-born playwright Diana Burbano, whom I had the great pleasure of interviewing at her home in Long Beach. Burbano told me all about her fascination with tracing her family heritage through 23andMe, and how playing stereotypical “hot tamale” roles as an actress led her to begin penning her own work.

Miranda held a roundtable featuring several cultural leaders “who are establishing new institutions and reimagining old ones,” including playwright Luis Alfaro, Lucas Museum of Narrative Art chief curator Pilar Tompkins Rivas and Redefine Entertainment co-founder Jairo Alvarado. The group was joined by scholar Ana-Christina Ramón, who leads UCLA’s Entertainment and Media Research Initiative.

“To speak of Latino culture in the United States is often to tell a story of absence, of underrepresentation and misrepresentation, of everything that is missing rather than all that exists. This will not be that story,” Miranda writes.

Vargas took a deep dive into the world of “punking” and “whacking,” styles of dance pioneered by gay men in the 1970s and celebrated today through various dance competitions. Vargas tells the story of Viktor Manoel, “the last founding member of punking alive today.”

“The movements also nodded to how they had grown up at a time when being gay meant not being ‘allowed to express love,’” Manoel explains. Writes Vargas: “To Manoel and his friends, punking spoke to the freedom they found in the club.”

Eve Recinos wrote about Meztli Projects, a Los Angeles-based arts and culture collaborative. Its project director and program co-creative director, Joel Garcia, is also a former co-director of the legendary Boyle Heights arts collective Self Help Graphics & Art. The story examines the group, which centers “Indigeneity into the creative practice of Los Angeles.”

Comedian and playwright John Leguizamo wrote an open letter to Hollywood calling for a “better pipeline for Latinos in movies, TV shows and plays. We need a system for our stories and our projects. We need executives to provide the greenlight.”

On and off the stage

Vargas writes about another Latino playwright, Octavio Solis, whose new play, “Scene With Cranes” “allows an intense sense of pain to surface.”

The world premiere launched the 20th anniversary season of CalArts Center for New Performance earlier this fall, and “provides the Latino matriarch a stage to display the complexities and brutal truths of what it means to be a mother, showing the power a mother has — and must withhold — to keep the family unit together.”

Vargas also penned a story about lauded Latino playwright Alfaro’s exit from Center Theater Group, after the associate artistic director announced his resignation on Facebook. Referring multiple times to the power of “change,” Alfaro wrote, “We have a long way to go in our pandemic recovery AND in our commitment to equity and diversity.”

Vargas notes, “While his resignation comes abruptly in the middle of CTG’s 2022-23 season, Alfaro has said in the past that change is native to theater.”

In and out of galleries

Christopher Knight heads to UC Riverside’s California Museum of Photography to take in an exhibit featuring the work of Christina Fernandez, who was born in L.A. in 1965 and has been on the faculty at Cerritos College in Norwalk for three decades. Her work, Knight notes, represents “an important pivot between classic Chicano art celebrating Mexican and Mexican American identity, raised in the face of oppressive stereotyping, and a more fluid and open-ended Conceptual structure that shakes things up.”

Knight also weighs in Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens’ acquisition of a 1784 portrait of Joseph Hyacinthe François-de-Paule de Rigaud, comte de Vaudreuil, painted by Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842).

“Lavish hardly begins to describe the painting. It’s a knockout,” Knight writes of the French work of art that was gained through the museum’s formal relationship with the Ahmanson Foundation.

Miranda journeys to the Bay Area for a dispatch about the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art exhibition “Diego Rivera’s America,” which features more than 150 paintings, frescoes, sketches and drawings. That display runs parallel to “the museum’s long-term display of ‘Pan American Unity,’ a portable 10-panel fresco Rivera painted in San Francisco in 1940 — his last mural in the U.S.”

Miranda writes, “The deep dives on Rivera make for compelling viewing in tandem with a separate exhibition in Los Angeles: ‘Reinventing the Américas: Construct. Erase. Repeat,’ currently on view at the Getty Center, which gathers several centuries’ worth of prints, watercolors, bookplates and maps that explore how the concept of ‘America’ has been depicted and defined. Together the shows offer an intriguing window into Latin American identity as it was constructed — and is now being deconstructed.”

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Just dance

L.A. Dance Project recently celebrated its 10-year anniversary gala at the estate of Jeanne and Anthony Pritzker in Beverly Hills, and Vargas was there to capture the action.

“Walking through the estate, dancers moved from room to room, arms outstretched to welcome everyone in before diving into a routine that kissed the ground of every part of the estate,” he writes, noting the particular pride of LADP artistic director and co-founder Benjamin Millepied at the group’s staying power.

Essential happenings

Matt Cooper is back with your guide to all the fabulous arts and culture events the Southland has to offer this week. Highlights include: Israel Philharmonic at the Renée and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall, Christiane Jatahy’s “Depois Do Silêncio” (After the Silence) at REDCAT, the 10th Art & Nature Festival at Laguna Art Museum and “My Body, No Choice” at the Fountain Theatre.

Finally, The Times is launching a new arts and entertainment guide penned by Vargas titled L.A. Goes Out. The dispatch will be delivered Wednesdays starting Nov. 16. Sign up here and never say, “I’m bored, there’s nothing to do,” again.

Moves

The Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach announced this week that it received a $2.5-million grant from the Perenchio Foundation. A flexible grant intended to help cover operating and other expenses, it is to be paid out over three years.

Passages

New Yorker cartoonist George Booth has died. The artist spent nearly half a century at the magazine, creating scores of offbeat cartoons featuring cats and dogs mixing with a variety of zany characters.

In Other News

— Author Joan Didion’s personal effects will be auctioned off at an estate sale on Nov. 16. The artifacts from Didion’s life in letters are on view now at Stair Galleries in Hudson, N.Y.

— The National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., is adding seven new faces to its ranks, including pandemic hero Anthony Fauci and film and television superstar Ava DuVernay.

— Two climate protesters have been sentenced to two months in prison for gluing themselves to Johannes Vermeer’s “Girl With a Pearl Earring” and its display.

— An oil sketch at Museum Bredius in the Hague, Netherlands, might be a Rembrandt, according to a Dutch art historian.

— The New Yorker’s winter art preview is out, and it contains all kinds of riveting Big Apple offerings including a collection of Nick Cave’s “Soundsuits” at the Guggenheim.

— A sculptural frame said to be the work of Jean Michel-Basquiat has been revealed to be the creation of Austrian musician and artist André Heller. Heller dismissed charges of forgery, calling the mix-up a “childish prank.”

— Cindy Sherman has joined the board of New York’s International Center of Photography.

And last but not least ...

Here’s what Elon Musk thinks of Twitter: “Because it consists of billions of bidirectional interactions per day, Twitter can be thought of as a collective, cybernetic super-intelligence.”

Um, right.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.