OCMA is (finally) finished — and it’s as good as it’s gonna get

- Share via

It’s Friday, I’m hungry and I’m thinking about omurice. I’m Carolina A. Miranda, art and design columnist at the Los Angeles Times, and I’m here with all the essential arts news — and dirty tree literature:

Edifice complex

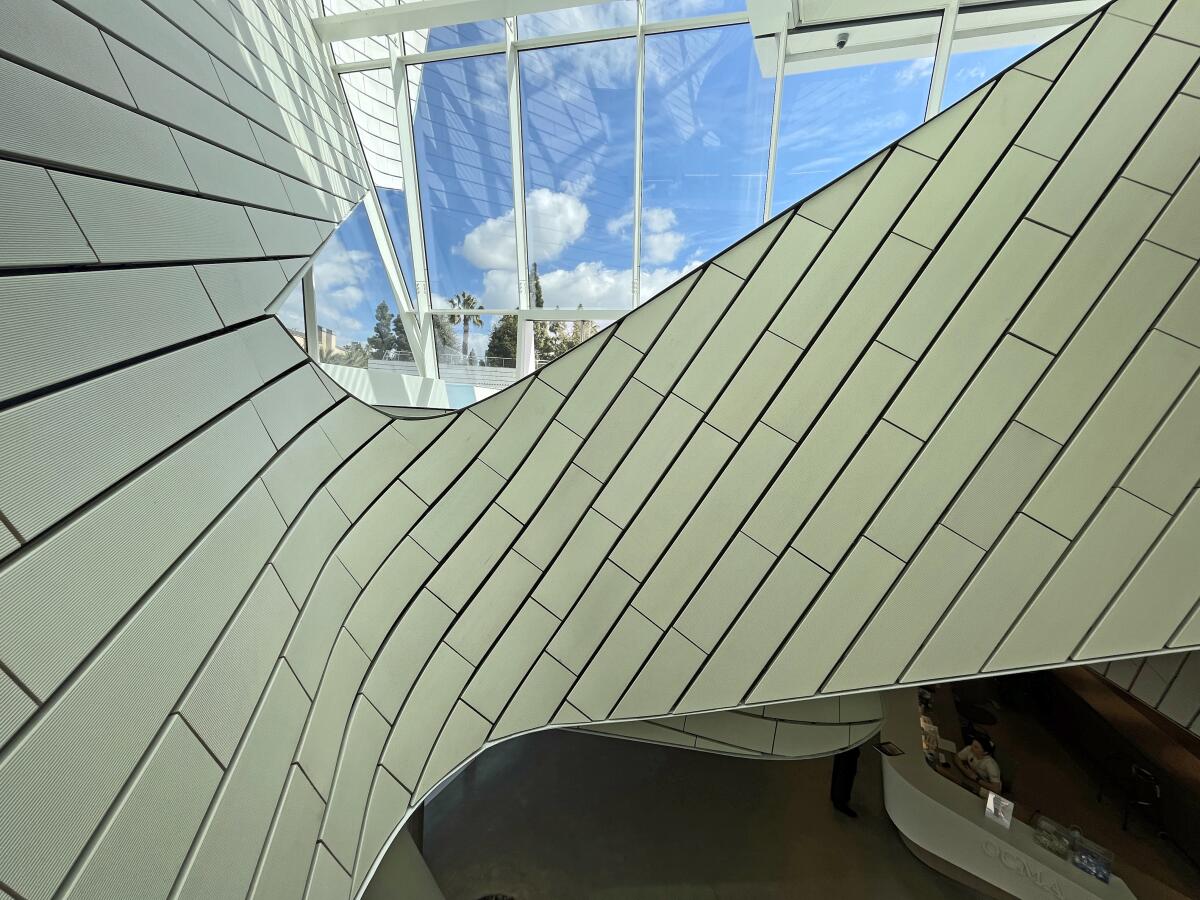

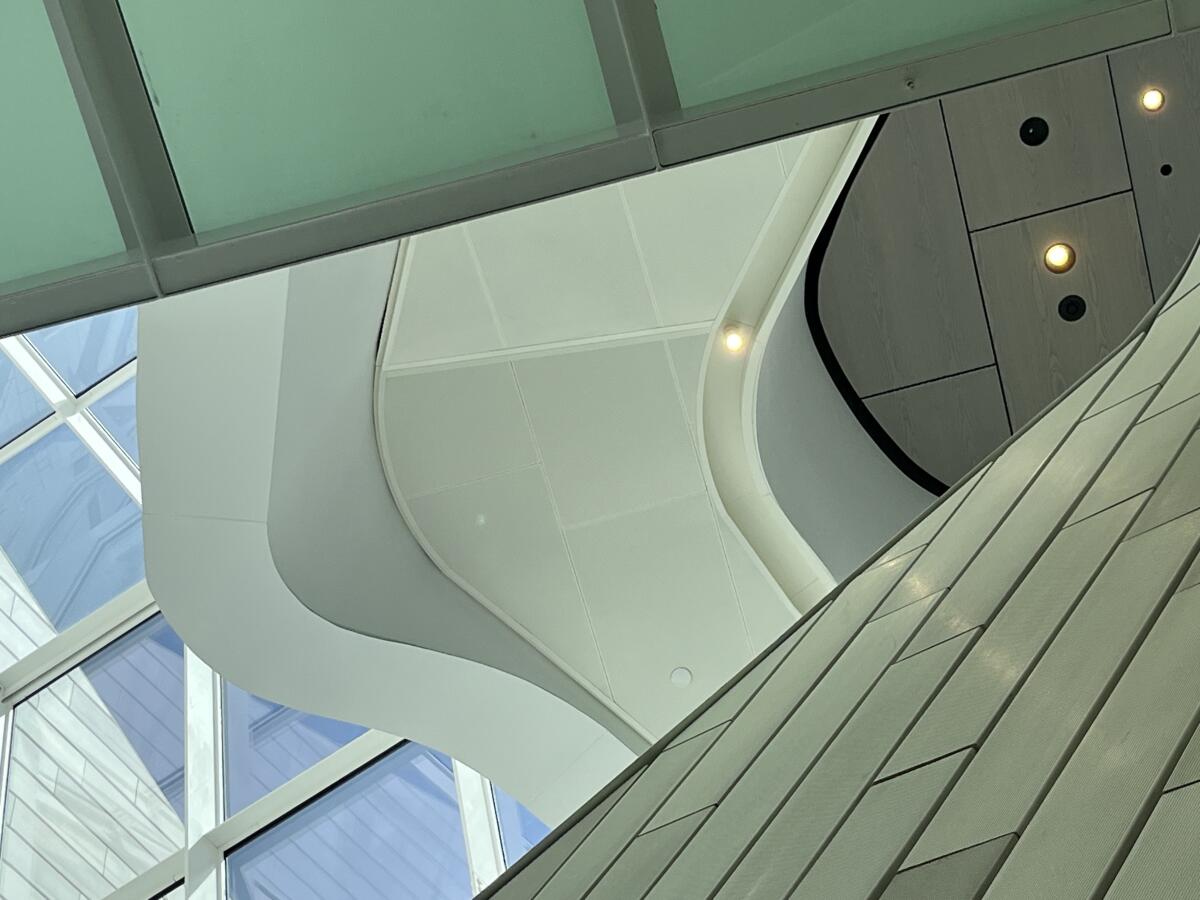

In late January, the Orange County Museum of Art shut down for a few weeks to work on the construction of their new Morphosis-designed building — which had opened to the public in October despite being incomplete. At the time, I wrote about the mess: slapped-together trims, crooked custom tiles, boards in place of steel and ceiling panels in the torquing atrium that still bore the contractor’s handwritten notes. Early this month, I went back to have a gander at the completed product.

The short of it: It’s better, but not great.

While all the final materials have been installed and everything gleams under a fresh coat of paint, the finishes remain wildly imprecise. In many places, trims do not fully align. While ascending the main stairs, I caught sight of a gob of caulk poking out from behind one of the building’s custom terracotta tiles. $94 million doesn’t buy you what it once did.

It’s easy to dump on the contractors. But the contractors didn’t design this overwrought building, nor did they commission it. That falls to the Culver City-based Morphosis, led by Thom Mayne, and the museum’s board, which was led by David Emmes II when Mayne was first announced as the architect of record back in 2008.

Why, exactly, the museum’s stewards thought that a modestly budgeted institution such as OCMA was in need of such a complicated design is beyond perplexing. (At the time that Morphosis was brought on board, OCMA’s annual operating budget was about $4.8 million; currently it stands at about $8.5 million. For comparison, the Hammer Museum — which is about to unveil an expansion designed by Michael Maltzan — has an operating budget of about $29 million.)

The whole project comes off as a room full of trustees getting a little too excited about rubbing elbows with a starchitect, and not excited enough about considering the institution’s actual needs.

Make the most of L.A.

Get our guide to events and happenings in the SoCal arts scene. In your inbox every Monday and Friday morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The cosmetic hiccups are an issue, but the bigger problems for me are the ways in which this building serves the art it was intended to harbor. As I noted in my last piece, the ground floor galleries lack definition, and the ones on the second floor occupy, respectively, a hallway and an awkwardly shaped mezzanine space.

But hey, the handsome roof deck will be great for galas. I look forward to seeing it on Instagram.

In and out of the galleries

Simone Forti, the L.A.-based artist known for her democratic approach to dance and movement pieces rooted in vernacular action, is the subject of a one-woman survey at MOCA Grand. This concise show, curated by Rebecca Lowery and Alex Sloane, with Jason Underhill, has moments that mesmerize and others that quite literally move the viewer into action, writes The Times’ art critic Christopher Knight.

If you haven’t already, by all means read Catherine Wagley‘s profile of Forti in Momus. As choreographer Yvonne Rainer once wrote, Forti was an artist who brought “the god-like image of the dancer down to human scale.”

Knight has been tooling around the desert to review Desert X 2023, the fourth edition of the Coachella Valley biennial curated by Neville Wakefield and Diana Campbell. Of the current iteration, which he describes as “an otherwise bland affair,” Knight zeroes in on Matt Johnson‘s massive sculpture, “Sleeping Figure,” which creates the profile of a lounging figure out of freight containers. “Of the 59 commissions produced since the series launched in 2017,” he writes, “Johnson’s sculpture is among the very best.”

Plus, Wagley also has a profile of Betye Saar in the Boston Globe, tied to her current exhibition at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum — which parallels travel journals by Saar with the museum’s founder.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Here’s a fantasy job I want: a curator for movie sets. Contributor Emily Zemler writes about how Italian art curator Leonardo Bigazzi borrowed and commissioned works for Vasilis Katsoupis’ “Inside,” in which Willem Dafoe plays an art thief trapped inside the home of a wealthy collector. (This would be a great parlor game: Which wealthy collector home would you want to be trapped in?)

On and off the stage

Richard Gilman, writes theater critic Charles McNulty, “created space in American culture for serious dramatic criticism, aimed not at academic specialists or anxious cultural consumers but educated readers hungry for a deeper aesthetic engagement with the theater.” Now Gilman is at the heart of a warts-and-all book, “The Critic’s Daughter: A Memoir,” by his daughter Priscilla Gilman. In a tale that involves one very ugly divorce and anecdotes of fetishism, McNulty writes about “whether it’s possible to separate the critic from the criticism.”

Metro columnist Erika D. Smith caught a performance of “Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992,” as part of a Black Out Night at the Mark Taper Forum. The play, about the fractious conditions that led to the ’92 uprising, was originally conceived and performed by Anna Deavere Smith. Now it is being staged with a cast of five, in a production directed by Gregg Daniel. First presented in 1993, “Twilight” suggested “a path forward” for Los Angeles, writes Smith, in a smart and frank appraisal. But she worries that “all these years later, audiences are too exhausted, too jaded or maybe too overwhelmed to look through it to see the people on the other side.”

Classical notes

The prodigal Zubin Mehta returned to lead the L.A. Phil at Disney Hall, in a performance of Mahler’s Symphony No. 3. Times classical music critic Mark Swed reports that, at 86, Mehta’s movements are far more subdued; at times, imperceptible. But the sound he coaxes from the orchestra remains singular and bold: “The cheers at the end were like those for a rock concert.”

What I’m reading

This week, the New Yorker dropped a big piece on H.G. Carrillo, a novelist whose Cuban identity ended up being a fiction, along with countless other details from his life. He was actually born Herman Glenn Carroll in Detroit. Two years ago, our arts editor Paula Mejía (who had yet to join The Times at that point) wrote about the deceit in Rolling Stone. The fact that she is a (Latina!) former student of Hache‘s — his nickname — was particularly poignant. And so are her investigations into why assuming the mantle of Afro Latino identity may have been so easy to do within the context of U.S. society. A must-read.

Passages

Fujima Kansuma, a master kabuki dancer who taught the form to generations of Japanese Americans, and who during World War II was held in U.S. incarceration camps where she continued to teach, has died at the age of 104.

Designer Rolly Crump, who helped give Disneyland attractions such as It’s a Small World and the Haunted Mansion, their indelible look, is dead at 93.

Phyllida Barlow, a sculptor who infused monumental sculpture with vernacular materials and a sense of ephemerality, has died at 78. Christopher Knight wrote about her impactful show at Hauser & Wirth one year ago: “You’ve never seen anything quite like it — or maybe you have, which is part of their charm. Barlow pulls from a variety of established artistic forms, mixes them with her own peculiar sense of invention, then seems to drop them into an industrial-strength blender to produce sculptures of grand, vivifying ambition.”

In other news

— Oh that story about the world’s worst art job listing is the gift that keeps on giving. Artnet concluded that it was put up by artist Tom Sachs and Gagosian director Sarah Hoover. Now Katy Schneider and Adriane Quinlan at Curbed go all in on what it’s like to work in Sachs’ studio. In one word: yikes!

— It’s not all single-family homes and suburban sprawl: Frances Anderton delves into the history of the Los Angeles apartment in a new book. Greg Goldin reviews.

— Also, I’m here for Mimi Zeiger‘s take on Frank Gehry’s Grand L.A.

— Architecture critic Oliver Wainwright is not having the Eric Owen Moss compound that has sprouted in Culver City’s Hayden Tract — from the design to the environmental toll.

— All the Silicon Valley layoffs and office closures are a bonanza for the used furniture market.

— New Angle: Voice, a podcast that explores the lives and careers of women architects, has a great new episode on Ray Eames. ICYMI, do not overlook the episode on Helen Fong, who helped shape the look of Googie in Los Angeles.

— Kehinde Wiley is about to open a major solo show at the De Young in San Francisco that is inspired by the toll of systemic violence on Black people. Dionne Searcey of the New York Times looks at how this and other shows are making space for grief.

And last but not least ...

Adding to my reading list: “Cultus Arborum: A Descriptive Account of Phallic Tree Worship.”

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.