Review: Coronavirus closed Craft Contemporary’s biennial, but it can’t stop our love of the art

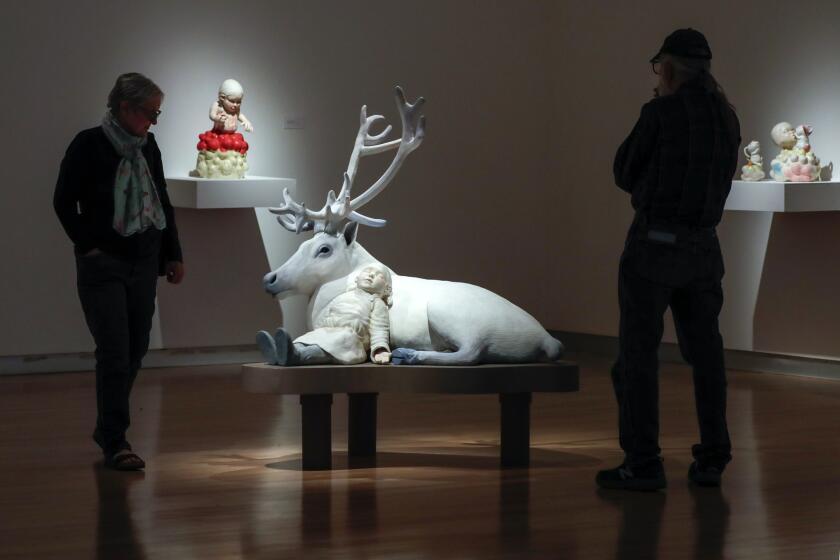

Craft Contemporary, formerly called the Craft and Folk Art Museum, has followed its inaugural clay biennial of 2018 with a second iteration that is consistently engaging and more tightly conceived than the first.

Even though the museum has closed through March 31 because of coronavirus concerns, The Times is publishing this review, written before the closure, as a way of sharing the work virtually.

The biennial — “The Body, The Object, The Other” — gathers work by 21 artists, about half based in L.A. Like the first biennial, this show was curated in-house by Holly Jerger and Andres Payan Estrada.

If the body feels like an obvious choice as a unifying theme for a group show of ceramic sculpture, it is — but it is also inexhaustible and persistently relevant. Everything made in clay relates to the body in some way, if only because of the physical directness of working with the medium. The most invigorating work in the Craft Contemporary show approaches familiar categories — the body as representational subject, the body as form, especially the body as agent.

Nearly all of the representational work involves fragmentation, distillation and some sort of distortion. In Raven Halfmoon’s formidable pieces, a whole or partial head repeats upward like a palpable echo, rising and insistent.

Cynthia Lahti’s figures shape-shift from clay to stuffed animal, photograph or tree branch, from one form of graceful to another, or from delicate to endearingly clumsy.

The grotesque, abject and extreme come into captivating play in a composition of multiple objects by Meghan Smythe, as well as in a disembodied hand by Roxanne Jackson, its back a pelt of dark fake fur, its nails like golden talons and its palm sprouting mushrooms. The erotic fetishes of Jason Briggs, all surface persuasion and kinky permutation, feel descended from the surrealist photographs of Hans Bellmer.

Among the most involving works here are those centered on process, on the body as maker. For Cannupa Hanska Luger‘s participatory project, “Something to Hold Onto,” visitors contribute their own grip-formed beads of clay, each like a little raised fist of solidarity.

In Cassils’ immersive “Ghost,” viewers enter a small, unlighted chamber with a raw clay floor and a pulse-quickening audio track of a past performance, in which the artist confronted and assaulted a 2,000-pound block of clay in complete darkness. Grunts, hisses, growls and urgent exhalations are overlaid by the sound of the artist’s accelerating heartbeat.

Brie Ruais uses her body as unmediated tool too. Playing beside two wall-mounted, tiled installations is a video that chronicles how she works, kneeling on a mound of raw clay equivalent to her own weight and using heels, hands and elbows to spread and skid the clay into a large X, a crude but most authentic signature.

Nicole Seisler transforms the preparatory act of wedging clay (a kneading process to establish consistency and eliminate air bubbles) into a mark-making ritual, enacted on the wall rather than on a work table. Practice turned performance, the action endures — until the end of the show — as mural, a patterned weave of residual traces.

“The Body, The Object, The Other” has its weak spots: work that is excessively literal, a handful of pieces that aren’t recent. But the show, scheduled to run through May 10, makes a lively addition to the conversation in clay.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.