Lillian Michelson built Hollywood’s most famous research library. Can someone give it a home?

- Share via

Where does a 500-pound Hollywood research library sit?

This is not a rhetorical question.

For the record:

10:02 a.m. Aug. 17, 2020In an earlier version of this story, the second reference to Harold Michaelson mistakenly identified him as Howard and a reference to production designer Ken Adam mistakenly identified him as Ken Adams.

Once upon a time, every studio had one, and the Harold and Lillian Michelson Library, a vast and storied institution known to generations of filmmakers, was one of the best — an important piece of Hollywood history. It still is.

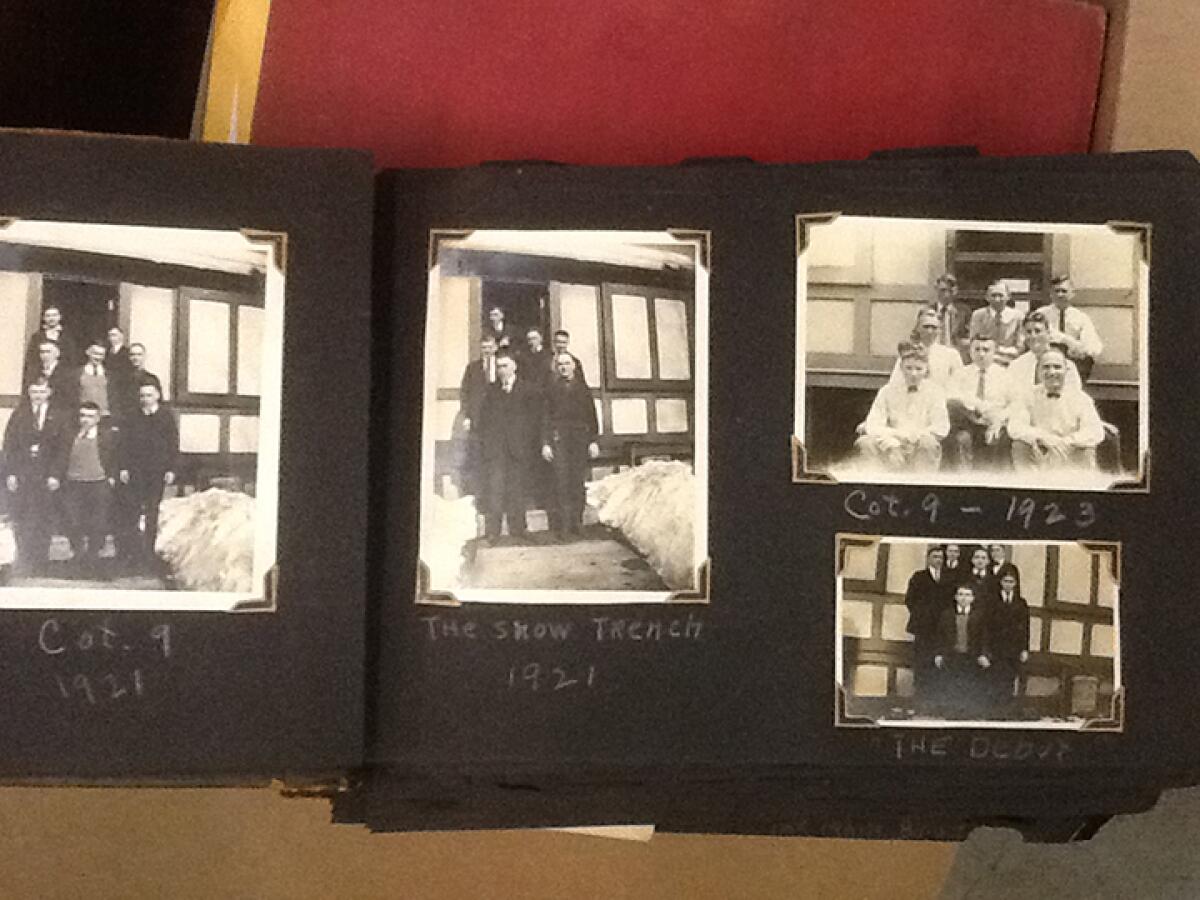

Its roots go back to the Pickford-Fairbanks Studios, established in 1919 on a corner of Formosa Avenue and Santa Monica Boulevard in West Hollywood. Renamed United Artists Studio in the 1920s, the Lot, as it came to be known, eventually became the site of Samuel Goldwyn Studios. In 1961, Lillian Michelson, wife of renowned storyboard artist Harold Michelson, became a volunteer there, and eight years later, she made the library her own.

For more than half a century, the Michelson Library was a working resource for filmmakers, a place where directors, art directors, production designers and prop masters found inspiration, accuracy and ideas. Lillian’s research was used for films as varied as “The Birds,” “Rosemary’s Baby,” “Fiddler on the Roof,” “Reds,” “Scarface,” “The Hunt for Red October” and “Full Metal Jacket.”

It was a nomadic life — over the years, Lillian and her collection could be found at the American Film Institute, Francis Ford Coppola’s Zoetrope Studio, Paramount and DreamWorks — but the library’s mandate never wavered.

Need to know what a 1940s Los Angeles gas station or the interior of a Cold War submarine looked like? What about different types of gladiator helmets? Hoping for some direction on what kind of undergarments women wore in a Russian shtetl or what a shtetl itself looked like?

Inevitably, Lillian had the answer in her library, and if she didn’t, she would find the information elsewhere and add it to her library.

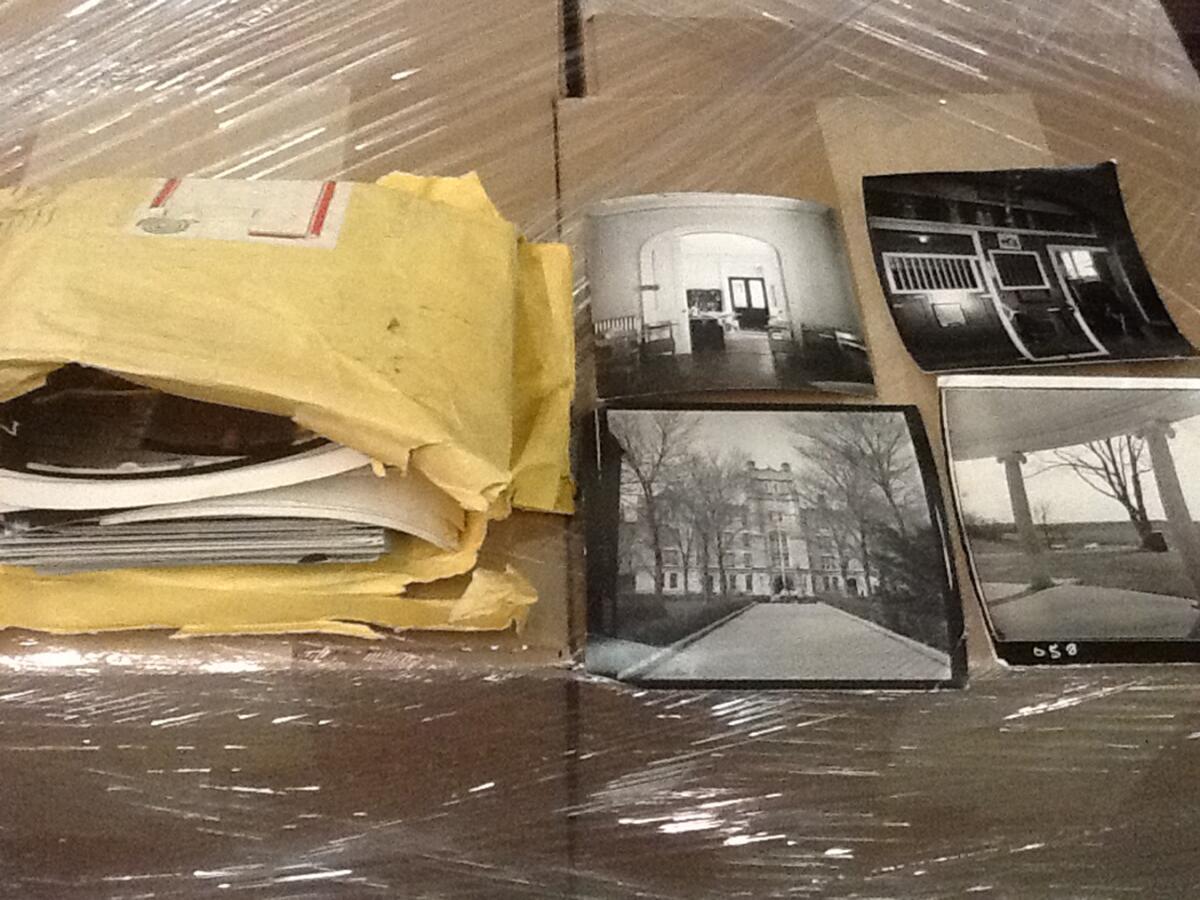

Which, since her retirement five years ago, sits in a climate-controlled warehouse on the Westside of Los Angeles — 1,594 boxes filled with 5,000 books and just as many rare and historic periodicals; 30,000 photographs (architectural, set decoration, prop and set stills); and another 6,000 items including clip files, sketches, set drafts and production notebooks.

It’s a unique collection of visual resources but despite its starring role in the 2015 documentary “Harold and Lillian: A Hollywood Love Story” and continuous efforts by Lillian and her many friends, no museum, college or Hollywood institution will take it on.

Its historic value is real but complicated. Although the library certainly contains items that qualify as Hollywood memorabilia, most of it does not. Much of what is stored in those 1,594 boxes are materials used in creating sets, costumes, backdrops, lighting and even scripts, rather than those things themselves. And these days, who wants to deal with 45 pallets full of boxes when we have the internet?

“The internet has been a boon to everyone,” says Lillian, “except my library.”

Harold Michelson died in 2007 and Lillian, 93, lives in the Motion Picture & Television Fund retirement community in Woodland Hills. She has been in quarantine since COVID-19 swept through the facility in the early days of the pandemic, and the state called in National Guard teams of nurses and medics to assist. Those teams are gone now, but the residents have not been allowed visitors for five months.

So Lillian talks on the phone about her library — which she very much wants to remain a library. “It needs to be digitized,” she says. “Everyone thinks you can find everything on the internet, but you can’t; you can only find the things that someone has put there.”

She finds it odd that no one has expressed interest in doing this, especially now. Although it would require a certain level of expertise, there may be no more socially distant work than sorting through books and photographs to create a website full of visual references.

She would do it herself, but she can’t: A failed shoulder replacement in 2011 led to a heart attack, she says, “And I never got back to work. It was not what I expected. “

::

Lillian Farber met Harold Michelson in Miami, where both lived, before World War II; after serving as a bombardier/navigator, Harold moved to Los Angeles and began what would become a legendary career as a storyboard artist. He convinced Lillian to join him, and they were married in 1947. They had three children, and eventually, like many women, Lillian began looking for something to do during school hours. In 1961 she began volunteering for librarian Leila Alexander at the Goldwyn Studios’ research library.

“We were practically the only women there,” she says. “I remember having to walk forever just to find a woman’s bathroom.”

Eight years later, when the studio decided to close its library, Alexander suggested that Lillian buy it. “I was so used to obeying her,” Lillian says, “that I did.”

The Michelsons did not have the $20,000 the studio was asking, so they borrowed against Harold’s life insurance policy. But even then finding a home for a research library was a challenge.

Eventually, the American Film Institute offered Lillian the laundry room in its then-headquarters at the Greystone Mansion in Beverly Hills. She took it, only to discover, on moving day, that Goldwyn still owned the oak cabinets that many of the clippings were in; she would have to pay $20 extra for each.

“I ran around to all my friends, borrowing $5, $10 here and there until I had enough money to buy the cabinets too,” she says. “I still think that was pretty rotten of them.”

She charged for her research by the hour, beginning with $5 and then slowly moving to a career high of $75. By then she had moved three more times, to Francis Ford Coppola’s Zoetrope Studio in Hollywood, then to Paramount and finally to the library’s last functional home at DreamWorks Animation in Glendale.

“I never made any money,” she says. “Because I was always buying new books. I had eloped [with Harold] after a year in college and then there was no money for me to go back, so I always looked at my work as my college education. “

She is very proud of the fact that when asked for help, “97% of the time I came up with an answer.”

Although she did spend six weeks trying to help a producer who wanted to do a movie in India about a Brahmin marrying an “untouchable” before conceding “It could never happen.” However, she did manage to help Norman Jewison with “Fiddler on the Roof.” One day, she encountered a woman at a bus stop on Fairfax Avenue who had been a child in a Russian shtetl and knew just what women’s undergarments looked like in the early 20th century. Even more important, after weeks of reading through a variety of Jewish libraries, she found a journal that contained sketches of a shtetl, written by, more research revealed, a “man who lived in Studio City.”

Lillian’s library grew apace with Harold’s renown as a storyboard genius — it was his artistry that gave us such memorable images as the schoolyard scene in “The Birds” and Dustin Hoffman — seen behind Anne Bancroft’s bent knee — in the poster for “The Graduate.” They became one of the most beloved couples in Hollywood (the King and Queen in “Shrek 2” are named Harold and Lillian for a reason).

All the while, the Hollywood research library, like many research libraries, was quietly going the way of the dodo.

“Research libraries of every sort are being abandoned or forgotten mostly because they take up too much space,” says Aaron Rich, a doctoral student at USC who just finished his dissertation on libraries. “But it’s important not to lose this information, these paper records. The internet,” he adds, echoing Lillian, “is only the things someone put on the internet.”

The role of research librarian, many times underappreciated, is also in danger of vanishing. “I don’t think it’s an accident that almost all of them are women, and that they’ve been erased from film history,” Rich says. “A lot of women’s work in Hollywood has been lost.”

Which is just another reason, Rich says, for someone to figure out a way to to continue using the library as Lillian did.

When Lillian retired, she offered her library to the Art Directors Guild, which did an inventory in 2014. But with its own very extensive library to organize and digitize, the ADG declined to accept the library as a gift.

”This is a union organization,” says Chuck Parker, national executive director of the guild, otherwise known as International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees Local 800. “There are legal parameters because we are dealing with members’ money. This is not our mission.”

This does not mean that Parker, or guild members, don’t value the library. “I used Lillian’s library all the time,” Parker says. “Back when it was in a rundown building at Paramount, and I was working on ‘Monk,’ [I’d] call her and say ‘Monk is going to be a PI and visit Sam Spade’s office. Can you find out what Sam Spade’s office looked like?’ And she’d say ‘come over in a few days, and I’ll have it for you.’ And she would.”

But those “few days,” Parker says, are a big reason so many research libraries have been abandoned. “The pace of things has changed so much. I don’t have a few days. When someone asks me for something now, I need to show it in a few hours. A brick and mortar research library, nobody’s got a place for this. What we need is an angel to come in and finance the digitization of her collection and collections like it and make it keyword searchable.”

::

For the last five years, the boxes have sat in storage, paid for, during part of that time, by Chris Meledandri, chief executive of Illumination studio, which produced, among many other films, the “Despicable Me” franchise. Meledandri also has fond memories of the library and of Lillian, whom he met when he was doing research for production designer Ken Adam.

“Ken asked me to go pick up some books from Lillian’s library, which was then at Zoetrope,” Meledandri says. “The minute I walked in those rooms, Lillian scooped me up and adopted me. I was 22, and the library had this salon aspect to it.” A few years later, Lillian gave Meledandri a friend’s unpublished manuscript; although the project was never made, it did get a production deal with Fox, which launched Meledandri’s career.

“The library was a rich part of the moviemaking process,” Meledandri says, “and there’s a historic quality that I’d love to see preserved.”

When Thomas Walsh, former president of the ADG, asked him to help with the financial costs, Meledandri said yes. But storage rates recently increased by almost 500%, Walsh said, and the time has come for the library to move on once again.

Walsh, who also spearheads the ADG’s Backdrop Recovery Project, has a lifelong devotion to preserving the physical remains of Old Hollywood. Over the last five years, he has overseen the cataloging and storage of the Michelson Library and, with the help of many Lillian fans, has tried to find a home for it. But all of the organizations approached, including the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, USC, UCLA, AFI and Lucasfilm Ltd., have declined. Many of them already have their own research libraries — the academy’s Margaret Herrick Library is world renowned. Others have scooped up parts of other studio libraries and have similar storage issues.

But none of these collections is as thoroughly attached to a single person like Lillian Michelson for the simple reason that there is no one like Lillian Michelson.

“Ideally, I’d like create a nonprofit to digitize it and grow it,” Walsh says. “But so far, I can’t find the funding. Lillian has trained so many archivists that it’s hard to believe there’s no one out there who could help.

“It would take a lot of money to maintain and staff,” he says. “I get that. But beyond the value of the library as a whole, there is so much material in it that’s unique. The photographs alone, 30,000 images going back to the beginning of United Artists —

it is not the kind of stuff that should wind up in a dumpster.”

To that end, Walsh and other friends of Lillian have created, through the sponsorship of the Film Collaborative, a nonprofit to save the Michelson library.

But for now, it just sits in storage — 1,594 boxes filled with the visual inspiration for six decades’ worth of films and the life’s work of one remarkable woman. All waiting for someone to offer it a home before it becomes landfill.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.