- Share via

As a boy growing up in Seoul, Ed Kwon collected books about magic. The craft became an obsession, and he pored over literature illuminating mysterious tricks of master illusionists.

One of the first things he noticed was that many of the volumes referenced the same place: a private club in Hollywood where the world’s top magicians congregated.

The Magic Castle.

He began to dream about performing at the venue, envisioning himself as a conquering neophyte who could captivate a room of bejeweled guests with the flash of his playing cards.

For years, Kwon fixated on the Castle, the mansion that serves as the clubhouse of the Academy of Magical Arts, a group of about 5,000 magicians and enthusiasts dedicated to the celebration and preservation of the performing art. Eventually, he visited the facility in 2015 for a paid workshop, and a tour afterward reduced him to tears. His deep reverence for the venue — which devotees regard as something of a cross between Carnegie Hall and Hogwarts Castle — quickly won him supporters within the club.

Before long, his hard work earned him a chance to perform on the stages he’d read about as a boy. But not long after his Magic Castle debut in 2017, an ugly encounter forced Kwon to reconcile his childhood fantasy with a different reality.

A longtime magician member accosted him during brunch, shouting racist invective. “He used his hands to make slanted eyes and [said] the stereotypical Chinese — something along the lines of, ‘Ching hong chong,’” said Kwon, 24. “What he did and said was so out of place, it hit me at a surreal level.”

Kwon didn’t speak up at the time in part because he thought it was an isolated incident. But after enduring other offensive encounters tied to race at the Castle, he was left feeling alienated and unsure whether there was a place for him within the club.

Kwon wasn’t alone in his disillusionment. This L.A. icon — home to arguably the most prestigious and exclusive magic club in the world — isn’t quite what it appears to be.

In interviews with The Times, 12 people — among them guests and former employees — accused Magic Castle management, staff, performers and academy members of a variety of abuses, including sexual assault, sexual harassment and discrimination on the basis of race or gender. Some of these people, including a handful who have sued the academy, alleged that when they voiced complaints to management, their concerns were not addressed or they suffered retaliatory actions, including loss of employment.

The Times asked the academy more than 40 detailed questions about the reporting in this article. In a written response, Randy Sinnott Jr., the president of the organization’s board of directors, did not address the substance of any of the allegations, nor did he directly respond to any of The Times’ questions. Sinnott declined interview requests.

“The Academy of Magical Arts and its Board work to provide a safe and welcoming environment and experience,” Sinnott said in his statement, noting that he spoke for the academy and the Magic Castle. “All claims brought to the attention of the Board or management are treated seriously and professionally.”

The Castle is now wrestling with these allegations as it remains temporarily closed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. A fractious summer dialogue on Facebook about the claims pushed the academy’s board of directors to engage a law firm to conduct an investigation into “alleged inappropriate workplace conduct” — one that members said scrutinized the organization’s general manager, Joseph Furlow.

The board issued a statement to members Oct. 14 announcing completion of the months-long inquiry, saying that “the findings were serious and broad-spanning, covering management, culture, human resources, operational systems and processes, and the need for systemic change.” It did not disclose the details of the law firm’s report. Sinnott said the organization is working with a management consulting firm to assist “in implementing the resulting recommendations.”

One of the accusers, Stephanie Carpentieri, attributes her experience at the Magic Castle to a “corrosive corporate culture” there. A former waitress at the Castle’s restaurant, Carpentieri alleged in a 2019 lawsuit that while at work, she was sexually assaulted by a busboy who groped her breasts on multiple occasions and grabbed her vagina and buttocks in one instance. According to the complaint, she pleaded with management to reassign the alleged offender, but her superiors never took action. She claimed she was fired in retaliation for raising the issue. The academy, the busboy and Carpentieri’s boss denied her allegations in a court filing.

I do have hope that shining a light on this stuff will make a change, because the Magic Castle ... should not be tarnished by this atmosphere of violence and harassment.

— Stephanie Carpentieri

Carpentieri, 38, told The Times that the culture that permeates the Castle is one of “not believing women.” Academy members said the organization’s leadership often demonstrates an old boys’ club mentality by not addressing people’s concerns about claimed misconduct and not holding alleged wrongdoers accountable. And several lawsuits filed by former employees allege that no action was taken by management after they brought complaints to their superiors, managers or human resources workers.

From 2011 to 2019, the academy was sued four times by former employees, including Carpentieri, alleging violations of the Fair Employment and Housing Act, which protects against sexual harassment, discrimination and retaliation. Settlements of undisclosed terms were reached in three of the cases; Carpentieri’s matter is ongoing in L.A. County Superior Court.

“I just felt betrayed,” Carpentieri said. “I worked there for six years — I did my job well. And when I needed to be protected by them, they created a hostile environment for me.”

A beloved venue unmasked

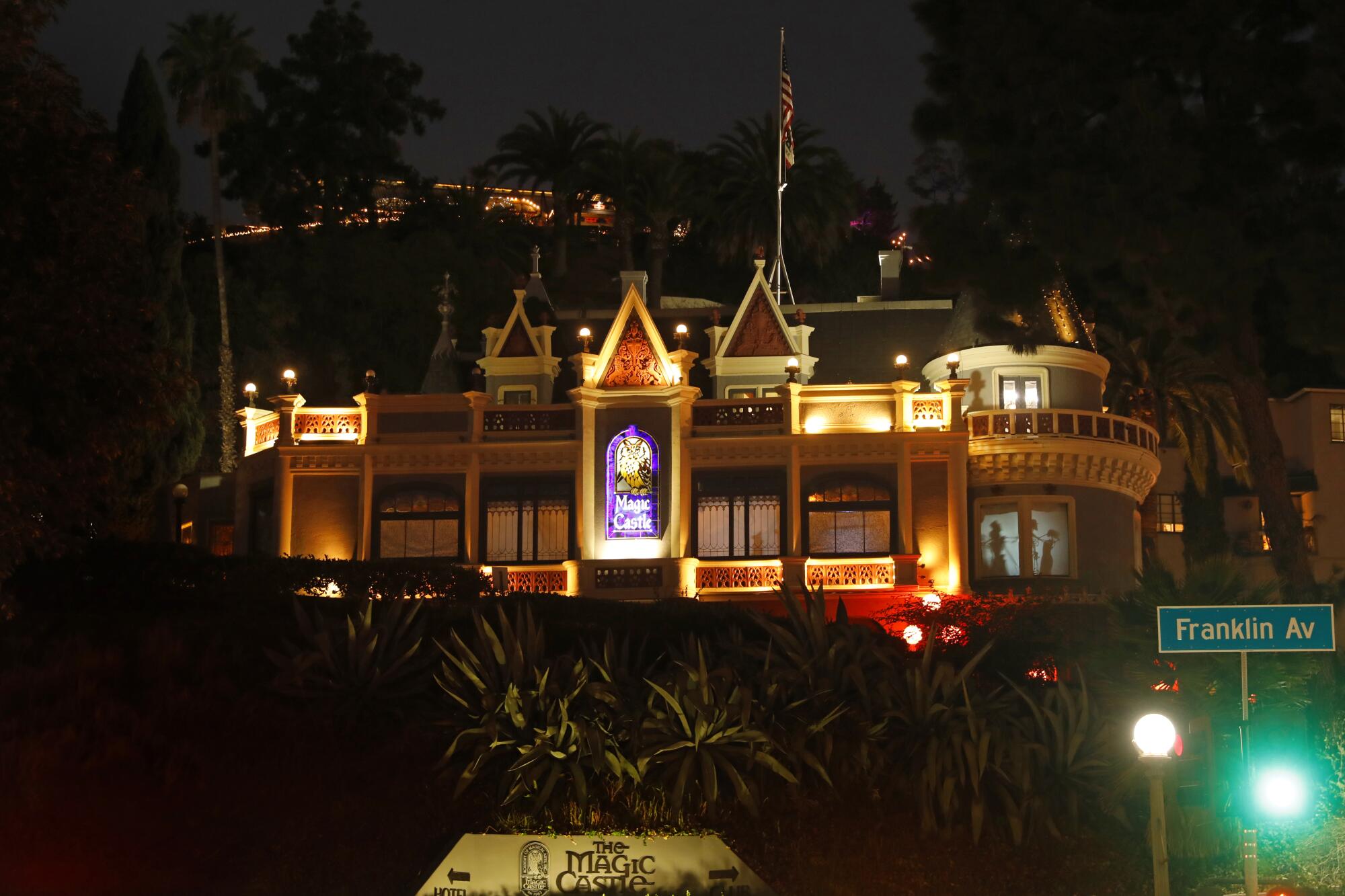

The turreted mansion that’s home to the Academy of Magical Arts is an imposing Chateauesque structure looming over Franklin Avenue.

It was built as a private home in 1909 for businessman Rollin B. Lane, and around 1960, screenwriter Milt Larsen set his sights on turning the building — by then run-down — into a private clubhouse for magicians.

Larsen’s brother Bill incorporated the academy in 1962, and a year later, their family opened the Magic Castle. Since then, the academy, a nonprofit public benefit corporation, has become a lucrative enterprise: In 2019, it generated revenue of $21 million and net income of $1.39 million, according to its annual report.

Magicians must audition for admittance to the group, members said, and pay about $800 in annual dues to the academy, which describes itself as a “social order dedicated to the advancement of magic.” Among the membership benefits: the opportunity to perform in the venue’s “impromptu” areas. Non-magicians pay more than $1,000 a year for associate memberships with fewer perks.

The Castle, which the academy leases, is a popular tourist attraction, though getting in isn’t so simple for non-members, who almost always need an invitation from a member. Part of the club’s appeal has long been its celebrity members, among them Cary Grant, Johnny Carson and Neil Patrick Harris, the last of whom served as president of the board of directors from 2011 to 2014. In 2016, Ridley Scott’s production company signed on to produce a yet-to-be-made narrative film about the Castle, and the venue’s appearances on TV shows such as “The Magician” and movies including “Lord of Illusions” have further burnished its reputation.

But the Castle also has been depicted as stodgy and out of step with the times. A 2016 episode of Netflix’s “Love” poked fun at the self-serious nature of performance magic and the venue’s strict dress code, which requires that men wear ties in the evening and suggests women bring along “elegant sweaters or shawls” due to the air-conditioning. And the magician ranks of the roughly 5,000-person academy, which members say is largely white, also are dominated by men: A 2019 study by one member found that female magician membership in the organization was 12% at the time.

The academy’s embrace of tradition is, for some, part of its charm. However, the way it has long operated has been called into question by lawsuits from former employees.

Workplace claims

When Carpentieri began working as a server at the Castle in 2012, she was pursuing an acting career and had gained some momentum after booking a recurring role on the TV show “Franklin & Bash.”

The job made sense for Carpentieri, giving her the flexibility to seek acting opportunities. It paid well too. She soon found that many of her new co-workers were collegial, and she also enjoyed the magic shows, which she said left her “in awe.”

But she came to conclude that “there is something that’s definitely tarnishing the place.”

That something, Carpentieri claimed in her October 2019 lawsuit, was management’s inaction after she reported multiple sexual assaults allegedly carried out by busboy Hector Portillo to her superiors, among them Furlow, the general manager.

According to the complaint, in late 2015 or early 2016, while at work, Portillo allegedly rubbed his crotch on Carpentieri and groped her breasts, behavior he repeated a few times. Soon thereafter, she reported the incident to her supervisor, the complaint said.

But Carpentieri said in an interview that her supervisor told her “nothing would be done about it.”

Then in March 2016, while Carpentieri was working, Portillo allegedly approached her from behind, reached under her skirt and grabbed her vagina and buttocks, according to the complaint.

She said that as the unwelcome behavior escalated, she began switching shifts with other employees to avoid being around Portillo. “I wasn’t being protected by my employer,” Carpentieri said, echoing claims in her lawsuit.

The academy and Portillo denied Carpentieri’s claims in a court filing. Attorneys representing Portillo did not respond to requests to interview their client.

Carpentieri also faced verbal and physical abuse from dining room manager Mikael Hakansson, her lawsuit alleges. The complaint describes several instances of Hakansson’s aggressive and violent behavior, including grabbing Carpentieri by her coat and dragging her away from a guest whose order she was taking, and pushing her in the stomach.

“There were times that I definitely feared for my safety,” she said.

She said that Hakansson’s alleged misbehavior set the tone in the workplace, empowering Portillo. “If somebody is an abuser and they see that women aren’t being heard over and over and they’re not being protected, they feel like they can do whatever they want,” Carpentieri said.

Hakansson, who has denied Carpentieri’s claims in a court filing, left the Magic Castle two years ago. According to the lawsuit, Hakansson departed after he was suspended for failing to report an unrelated incident in which a guest stabbed a server with a butter knife.

Attorneys representing Hakansson did not respond to requests to interview their client.

In 2017, the complaint alleged, Carpentieri emailed Furlow and a human resources employee about issues including Portillo’s assault and Hakansson’s “assaultive behavior.” According to the lawsuit, Furlow did not respond “to the substance of her complaint.” Still working alongside Portillo a year later, Carpentieri met with an executive in human resources and requested that Portillo no longer work with her, the complaint said.

A few months after that meeting, Carpentieri was fired. The lawsuit alleges her termination was a retaliatory act in response to her complaints of misconduct, which the academy has denied.

“I do have hope that shining a light on this stuff will make a change, because the Magic Castle ... should not be tarnished by this atmosphere of violence and harassment,” Carpentieri said in an interview, reprising claims from her lawsuit.

A former server at the restaurant who worked with Carpentieri for six years said Carpentieri told him about Portillo groping her multiple times — often shortly after the incidents allegedly occurred. The former server, who requested anonymity because he fears reprisal, said Carpentieri also told him about Hakansson pushing her and told him that when she complained to human resources and Furlow about her mistreatment, no action was taken and management “didn’t believe her.”

Furlow did not respond to questions about Carpentieri’s allegations. A trial in her case is set for August 2021.

Carpentieri is not the only former female employee to have issues with Furlow and other managers’ handling of a serious complaint.

In March 2013, Terry Lee Lamair — who’d worked as a bartender at the Castle for four years — sued the academy in Los Angeles County Superior Court, saying she’d been harassed on the job. According to her complaint, Lamair, who began working at the venue in 2008, first experienced trouble after a co-worker, Freddie Hernandez, asked her to meet him “outside of work hours.” Lamair’s lawsuit alleges that she complained to her superior about the claimed harassment, but no action was taken against Hernandez, who died in the 2010s, according to court documents.

Instead, the lawsuit alleged, Lamair’s supervisor — food and beverage manager David Bucks — also began sexually harassing her, referring to her vagina as the “Grand Canyon.” Lamair claimed she was also fielding inappropriate comments from her co-worker Nicholas Manelick, who said in front of her on approximately a weekly basis, “Oh, make me cum.” In 2012, Manelick’s behavior escalated, she alleged: He suggested she “spread [her] legs for daddy” and give him oral sex as a “prize.”

The academy, Bucks and Manelick, all of whom were named as defendants, denied the allegations in a court filing.

In March 2012, the complaint alleged, Lamair met with Furlow and Bucks to discuss the harassment claims; a human resources representative was not present. Though the closed-door meeting was meant to remain confidential, Lamair said numerous co-workers soon told her they’d learned details of the discussion.

Furlow and Bucks did not respond to requests for comment about the matter; Manelick declined to comment.

Subsequently, Lamair alleged, her work hours were reduced. She soon took a leave of absence and went on disability pay “due to the medical condition created by the sexual harassment and subsequent retaliation,” according to the complaint. A few months later, she informed the academy that she would stop working at the Castle, citing “continuing sexual harassment” as a reason for her departure, the lawsuit said.

In response, attorneys for the defendants argued in part that there was no evidence the harassment Lamair claimed to have experienced “was ‘unwelcome,’ as required by law,” citing conversations between her and co-workers in which she used lewd language.

According to court documents, Lamair and the defendants settled the case in 2014.

Lamair did not respond to a request for comment, and her lawyer, Stan Grombchevsky, declined to comment, citing confidentiality laws.

Management questions

As academy members have watched various lawsuits unfold, some have expressed concern that enacting much-needed change at the Magic Castle will be difficult under the current management — led by a man himself once accused of sexual harassment.

General manager Furlow, who was hired in 2012, has by many accounts been able to improve business at the Castle, whose financial health was poor in the mid-2000s, several members said. A glowing 2016 profile of Furlow by online publication Long Beach Post said that he’d improved attendance at the Castle by upping the quality of magic on display and offering more of it. In the story, Furlow boasted that annual revenue had hit about $15.5 million in 2015, nearly double what it was the year he took over.

But a recently uncovered lawsuit filed against Furlow nearly a decade ago — when he was clubhouse manager of a San Diego country club — has proved to be a flashpoint in the ongoing reckoning, with academy members heatedly discussing its allegations online in recent months.

In 2011, Kristen Dawson, a food and beverage manager supervised by Furlow, sued him and the Country Club of Rancho Bernardo in San Diego County Superior Court, alleging sexual harassment and other claims, saying that Furlow asked her out to dinner and commented on her looks.

After Dawson rebuffed him, saying she wanted only a professional relationship, the lawsuit alleged, Furlow produced sexually charged emails he said he’d received from an account bearing her name. Dawson told club management that the email address in question wasn’t hers and that she hadn’t written the messages, and she turned over her computer equipment to verify this; however, Furlow refused to do the same, the lawsuit alleged. Ultimately, according to the complaint, the country club was unable to determine who had sent the messages.

Dawson was fired a month after filing the lawsuit and then amended the complaint to include a claim of wrongful termination.

The country club and Furlow denied the allegations and successfully petitioned the court to throw out several claims in the lawsuit, including those related to Furlow, allowing him to exit the case. After years of legal skirmishing between the club and Dawson, the case was settled in 2015, and she received what her attorney Joshua Gruenberg described as “a very nice settlement.”

Dawson could not be reached for comment; the country club declined to comment.

In a statement, Furlow reiterated his denial of the allegations in Dawson’s complaint. “Simply filing a lawsuit in California does not mean the allegations in the complaint are necessarily true,” said Furlow, who declined requests for an interview. His statement added that “the court agreed with me,” noting that “the plaintiff was ordered to pay my costs.”

Former Magic Castle cocktail server Katie Molinaro got a sense of Furlow’s perspective on sexual harassment when she reached out to him via email in 2017 to address sexist comments being made in the academy’s official Facebook group. One member, she complained, was arguing that “alcohol deletes responsibility from the equation” when it comes to sexual misconduct — and his attitude was contributing to an environment in which other women felt “afraid to say anything because of fear of repercussions,” Molinaro said.

Furlow replied to say that he couldn’t understand why women might be wary of coming forward, explaining that there were strong women in his life who “would NEVER be afraid [to] report the truth or stand up for what is wrong,” according to a copy of the message that Molinaro shared with The Times and posted on Twitter.

“I just don’t understand the fear,” Furlow wrote.

‘Prey or props’

The three-story Magic Castle is a cavernous facility, one whose baroque decor — replete with hand-carved gargoyles, griffin statues and a trick bookcase that opens on command — helps create an air of mystery. A first-time visitor can easily get discombobulated amid the sprawling warren of theaters, bars and meeting rooms.

Sometimes, though, a guest can wind up feeling more than just overwhelmed. In fact, the building itself — its stages and stairs — have created opportunities to exploit women, according to interviews with several guests and members.

A particular area of concern is one integral to experiencing a show at the Castle: audience participation. Guests are routinely asked to assist in a trick, such as cutting a deck of cards. But women who volunteer to come on stage are often exploited, said Chris Hannibal, a magician member of the academy since 2013.

“The majority of the magicians that I have witnessed performing treat women as either prey or props,” he said.

In 2018, Andrea Kemp visited the Castle for an event with co-workers and took in a performance by magician Charles Chavez in the Cellar Theatre.

When Chavez asked for an audience member to help with the performance, Kemp volunteered. Chavez’s routine centered on trying to guess the card that Kemp had selected from a deck. It quickly got awkward. “He made it clear he wanted me to rub my card on my boobs,” said Kemp, adding that she told Chavez she would not do so, instead rubbing the card on an orthopedic boot she was wearing after having ruptured her Achilles tendon.

Chavez’s back was to Kemp, but it was evident she hadn’t complied, so the magician repeated his request. “He kept going, ‘No, you have to rub it on your chest,’” Kemp recalled.

Kemp was embarrassed — especially because her co-workers were watching. Trying to play along but unwilling to do as he wished, she rubbed the card on her neck, she said. Then, she said, Chavez told the audience he would “smell the card out.”

After some awkward stage banter, Kemp realized Chavez intended to move uncomfortably close to her. “I said no,” she said.

Kemp said that Chavez then “invaded” her personal space against her repeated objections and attempted to press his nose against her. “He leaned into me and tried to smell my chest and ... I pushed him off me,” she said. “I went back to my seat and ... stormed out mid-act. I immediately started crying.”

In an email, Chavez denied asking Kemp to rub the card on her breasts and said he did not touch her. “When I saw her upset later that night, I immediately went up to her and apologized if at any time I made her feel uncomfortable,” he said.

Garrett Celestin, a co-worker of Kemp’s, was there for Chavez’s performance and remembered how the magician disregarded her protests and “smelled her chest.”

“He got close enough that obviously it was very uncomfortable,” Celestin said.

Hannibal also witnessed the act and sought out security personnel to handle the matter. “She was assaulted in a place [where] she should have been meant to feel safe,” he said.

The majority of the magicians that I have witnessed performing treat women as either prey or props.

— Chris Hannibal

The next day, Furlow emailed Kemp to apologize for Chavez’s “deplorable behavior,” adding that he was “horrified and embarrassed,” the correspondence shows. A few days later, Furlow wrote Kemp to say that Chavez had been suspended from the academy for “conduct unbecoming” and that the matter would be addressed in an ethics hearing.

After the hearing, Chavez said, he was stripped of his academy membership and banned from the Castle.

Another woman — who requested anonymity because she did not want to hurt her standing as a member — described a similar 2013 experience while attending an instructional session that magicians receive as part of their membership.

The woman, then 23 and a new member of the academy, was asked to demonstrate a trick onstage. Afterward, a male magician approached her to compliment her on her skill.

“He was like, ‘You’re really tall, but I don’t mind the view,’ and then motorboated my chest,” she recalled. “I shoved him, said, ‘You’re disgusting,’ and left. I was 23. I was still so young that I didn’t understand I could go and say something.”

As soon as she got in her car, she called her boyfriend to tell him about the incident and vowed that she would never go to the Castle by herself again.

“She was very upset and distraught,” the woman’s boyfriend — whom she is still dating — told The Times. “It was a very upsetting night.”

There also is something of an open secret about the Castle’s interior architecture: A few seats at the venue’s main, ground-floor bar afford people seated there an intimate view of women as they ascend the central staircase. The stairs have a slatted railing, and with the steep angle, it is easy to “fully see straight up a dress,” Hannibal said.

“I have stepped in and stopped somebody from doing it on numerous occasions,” Hannibal said. “I have heard people joking about it: ‘These are the prime seats.’ I’ve stepped in and stopped the joking.”

When he has confronted men doing this, some simply turn away, but at least one got belligerent, Hannibal said, adding that at least half a dozen men are known to do this.

Hannibal said that when he recently raised the issue on the academy’s Facebook page, some people denied it was a problem, although others said that when they bring female guests to the club, they make sure to direct them away from the section of stairs where they could be unwittingly ogled.

Kayla Drescher, a magician member, said she was warned of the staircase.

“I was told during my very first week performing at the Castle that when I was wearing a short dress I should walk up the stairs a certain way because if you aren’t right up against the wall — and wearing any dress that’s knee-length or shorter — you can see right up,” said Drescher, who added that she’s since given similar advice to fellow female performers.

She said that she later told a male board member about the issue and that he responded, “Well, then maybe we need to instruct women not to wear low-cut tops and short skirts.”

Besides magician membership ranks that are overwhelmingly male, the academy is led by two bodies also composed mostly of men. According to an organization-wide email sent in November, five of the seven members of the board of directors are men, including its president, Sinnott. Six of the seven members of the board of trustees, which oversees “the magic aspects of the club,” are men, according to the group’s website.

Drescher said the board of directors has at times seemed indifferent to the idea of increasing the academy’s female membership and upping the number of female performers. In an April 2019 presentation to the board, she highlighted the Castle’s poor track record with women, sharing findings from a report she wrote on the matter.

Drescher’s report, a copy of which was provided to The Times, said that during each year from 2016 to 2018, female magicians were booked for less than 7% of the 700-plus performance slots, hitting a low of 4.4% in 2017. In the first four months of 2019, female magicians were given 22 of the 258 slots, or 8.5%. She also examined bookings for individual theaters at the Castle and found that in some years women had never been selected for certain rooms and times. For example, her report said that not one female magician had worked the late session in the Close-up Gallery, a prime venue, from 2016 through April 2019.

Drescher was allotted 20 minutes to present these findings while the board took its dinner recess, during which she also outlined how dressing rooms at the Castle did not allow for privacy.

“When we finished and asked for questions, one person started yelling at us and saying that everything we’d said was false,” she said. “He asked how we could accuse the Castle of doing these kinds of things — of saying it wasn’t a safe place for women.”

Drescher said a board member told her that he would follow up with her to pursue next steps; she said she never heard from him.

Allegations of racism

This year’s nationwide dialogue about systemic racism has sparked a period of introspection for many organizations and institutions, the academy among them. And several allegations of racism, disclosed to The Times after the summer protests over racial injustice, have highlighted this area of concern for some members.

Many of the complaints center on the use of racist language.

Hannibal, for example, said that while dining at the Castle last year he overheard a white member use a slur to describe the cooking of the Castle’s then-executive chef, Jason Fullilove, who is Black. “A very respected, very old white stage illusionist ... and his wife were dining in a different part of this room. His wife said, ‘The food hasn’t been as good since we got that Black man in the kitchen.’ And [the man] said something in the lines of, ‘Well you know, those N-words like to cook for themselves, for their own taste, and white people don’t like it quite as much,’” recalled Hannibal, who sanitized the magician’s use of the epithet.

Told of the man’s comments, Fullilove, who departed the Castle early this year, called them “hurtful.”

Brian Turner, a former Magic Castle cook who is Black, said that a handful of non-Black colleagues habitually used a racial epithet in the kitchen. “It was a whole lot of N-bombs being dropped all day, every day,” Turner said. “It was very uncomfortable.”

Turner, who was laid off when the facility closed in March, said those who used the slur refrained from deploying it when Fullilove was around. But they used it among themselves as “everyday vernacular” and directed it at Turner and other Black staffers, he said.

A person who worked in the kitchen at the time told The Times she also heard staffers use the slur.

Turner said he asked his colleagues to stop, but they would not. He said that he informed two sous chefs about the situation and that nothing was done, adding, “They didn’t care.”

Professional photographer Najee Williams, a magician member of the academy since 1990, described an encounter with Furlow that also had racial overtones. Williams had long served as the venue’s official photographer, but a 2014 negotiation between him and Furlow over renewing his contract turned bitter.

“I am your boss — you are to do what I say,” Williams said Furlow told him.

Williams said that when he explained that he had a strategic partnership with the academy — and that Furlow was not his boss — Furlow responded: “We have the land here and we’re allowing you to work it. Yeah, you pay us and everything, but we’re allowing you to work our land.”

Williams, who is Black, said the comment immediately brought to mind sharecropping. “It was one of those coded words, one of those dog whistles,” Williams said. “I think that he knew what he was saying. And if he didn’t, you’d have to be pretty darn ignorant not to know,” Williams said. “You’re talking to a Black man.”

Williams said he didn’t confront Furlow over his remarks because he didn’t want the manager to be able to accuse him of “playing the race card.”

After the dust-up, Williams said, his photography contract was not renewed.

Furlow did not respond to questions about the incident.

Some conversation about race-related issues at the Magic Castle has occurred on Twitter and Facebook — especially after the summer protests.

During the L.A. demonstrations sparked by the death of George Floyd, Castle management allowed law enforcement authorities to use its parking lot as a staging ground for their response. This upset some in the academy who support the Black Lives Matter movement and objected that members weren’t consulted, according to magician member Brandon Martinez. Some members, he said, took to the club’s Facebook group to express dismay.

This is not the club that our family envisioned. The Academy of Magical Arts, and its clubhouse the Magic Castle, were built on a foundation of love for the art of magic and love of community.

— Erika and Liberty Larsen

In response to the controversy, the board of directors issued a statement June 5 that expressed support for Black Lives Matter. It said the decision to allow authorities to use the parking lot was meant to “help ensure the safety of our building and the irreplaceable items inside” and should not have been interpreted as “a statement of support for bad actions, which was never intended.” The board also said it would match members’ donations to “organizations and programs that benefit social justice causes” — up to $50,000 in total.

As the online rhetoric intensified, members’ statements in support of Black Lives Matter were deleted from the group’s Facebook page, according to interviews and a review of messages on the website. On June 12, the board announced via the group’s page that moving forward it was to be used only for posts pertaining to “magic, art or entertainment.”

The board also retreated on its promise to match up to $50,000 in donations, saying in a mid-June Facebook post that it could not do so on the advice of its legal counsel. Instead, the board said it would spend up to that amount on the creation of a diversity and inclusion committee.

The online rancor led to a digital schism. Martinez and other members have formed a new, invite-only Facebook group for some academy members where they feel more comfortable discussing the club’s ills. “This is bigger than just the Magic Castle and Joe Furlow,” Martinez said. “There’s a lot of people that have experienced a lot of pain, and there’s been a lot of sorrow. And I want that to be treated with nothing but respect.”

In the June 5 Facebook post, the board of directors acknowledged concerns about its handling of issues related to race: “We admit our own past shortcomings in this area. We will work steadfastly for a more diverse and inclusive club in our membership, our performers, our staff, and our outreach.”

Leaving the Castle

The Castle hasn’t escaped the economic cataclysm caused by the pandemic.

Early this year, business at the Castle was strong. The academy reported total income of $1.68 million in February, up 2% from the same month in 2019, according to minutes from a board of directors meeting. But the venue closed in March, laying off about 95% of its staff, board minutes said — or 189 people, according to an email the academy’s leadership sent members.

Since the pandemic began, the academy has been mired in red ink, with monthly losses topping $300,000 on several occasions, according to board minutes.

The academy has sought and received partial deferrals on the rent it pays for the Castle. It has rolled out online magic shows and a to-go dining service, both of which generated modest profits in September, according to the minutes. No reopening date for the facility has been set.

Sinnott said in his statement that the academy looks forward to welcoming people back to the Castle “once COVID restrictions are lifted.”

“Despite the challenges imposed on all individuals and organizations by COVID, we are on track — with the continuing support of our members — to weather this pandemic and to keep the magic alive,” he said.

As for the internal investigation into alleged misconduct, the board’s October statement to members said that its ongoing implementation of changes recommended in the report would “continue over the coming months” but offered no details.

Sinnott expressed confidence that the “changes will create an even better experience for members, staff and guests.”

Informed of the nature of allegations in this story, Erika Larsen, daughter of the late academy founder Bill Larsen Jr., provided a statement to The Times that said she and her daughter Liberty are “deeply saddened and disturbed by these devastating reports” and pledged to “do everything in our power to help our community heal.”

“This is not the club that our family envisioned,” the Larsens said. “The Academy of Magical Arts, and its clubhouse the Magic Castle, were built on a foundation of love for the art of magic and love of community. The Larsens do not condone discrimination on the basis of race or gender, sexual harassment or any form of abuse and intimidation.”

Through Erika Larsen, Magic Castle co-founder Milt Larsen declined to comment.

What the founders envisioned is exactly the kind of community Kwon was looking for, but what he experienced was a different version of the Magic Castle. Five years after moving to the U.S. for college, Kwon returned to his native Seoul in June. He said he was in part fleeing a country whose ineffective response to the COVID-19 pandemic had led to widespread devastation. But the corroded culture at the Castle also factored into Kwon’s decision.

“I started to notice the things I didn’t like about this place,” said Kwon, whose Korean name is Kwon Joon-hyuk.

Over the years, Kwon, a member of the academy since 2018, grew closer to Castle employees and learned of their plight, including disputes over pay. In 2016, former Magic Castle bartender William Peters alleged in a class-action lawsuit that the academy violated labor laws by not paying hospitality workers overtime wages, among other claims. The case was settled in 2018, with the academy agreeing to pay $300,000 while denying any liability.

“If it wasn’t for the friendly staff that really treated me as one of their own, I don’t think I would have been so persistent,” Kwon said. “It was home. And I just did not appreciate that they weren’t being treated [with] justice.”

Since returning to South Korea, Kwon said he’s questioned his devotion to the Castle and considered leaving magic behind for good — a striking development for someone who, as a boy, taught himself English to read books on the subject. He’s turned down about 25 shows, accepting only a handful of one-off gigs in Seoul. And on Dec. 21, he will depart for a two-year stint in the South Korean army to fulfill his compulsory military service. While there, Kwon said, he won’t share that he’s a magician.

Magic isn’t the same for Kwon anymore. That may also be true for the Castle and its academy, which is hemorrhaging cash, contending with a lawsuit over the alleged abuse of an ex-employee, dealing with claims of racism and sexual misconduct, and facing an increasingly skeptical membership.

Kwon said there’s a perfect word in Korean to describe how he feels about the Magic Castle — one for which there is no English analogue.

Aejeung.

It means, he said, “love and hate combined.”

Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.