How does the Getty battle bugs? Squirrel-hair dusters and dental picks, for starters

Last March, as the lights went off in museums across California and galleries were shuttered in the first wave of coronavirus closures, a dangerous invader penetrated the Getty Museum in Brentwood. It crept into the darkened, quiet decorative arts galleries, which are filled with ornate furniture, delicate ceramics, rare clocks and intricately woven tapestries and rugs dating to the Medieval period.

And it was hungry.

The interloper was the webbing clothes moth, which feeds on silk, wool and other organic material. The insect infiltrated other parts of the Getty Museum as well, but posed a particular threat to the fragile textiles and upholstered furniture.

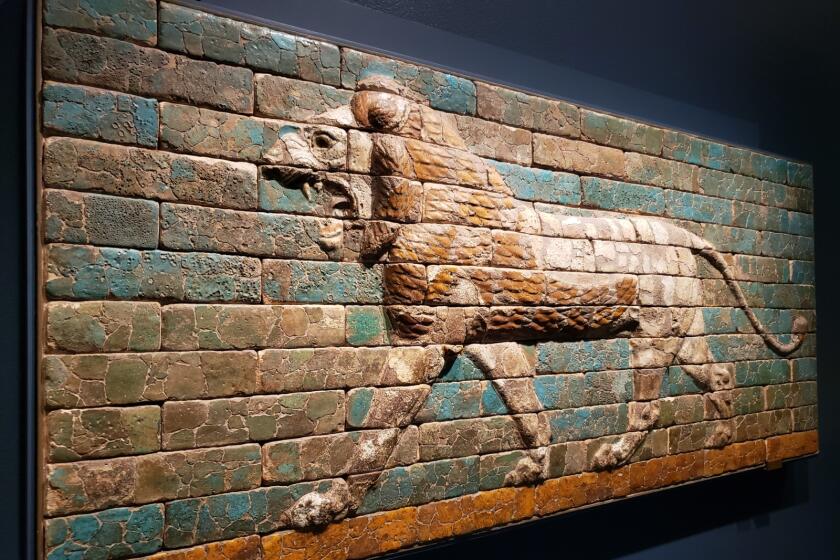

The Getty Villa ends its yearlong pandemic closure on Wednesday. On view: “Mesopotamia: Civilization Begins,” which goes back to the beginning, sort of.

As if COVID-19 shutdowns and the financial fallout weren’t enough, a noticeable uptick in unwanted pests, including insects and rodents, afflicted museums globally during the pandemic. Many insects are drawn to dark, quiet places. Empty museum galleries provided ideal environments, a feast of riches — quite literally.

The spring start of museum closures compounded the problem in many parts of the world, said Helena Jaeschke, a conservator who runs the British-based Pest Partners, which is dedicated to protecting heritage collections in southwest England.

“Spring is mating season in the Northern Hemisphere for pests, and that coincided with buildings closing down, with skeletal or no staff,” Jaeschke said. “There were no disturbances, like noise or lights, to limit pest activity. It was peak conditions for pests to spread.”

The Getty Museum took advantage of the extended COVID-19 closure to execute an intensive moth remediation program that involved nearly every department and took about 6,000 hours. (The Getty Center in Brentwood remains closed to the public, but the Getty Villa in Pacific Palisades has reopened.) Though the Getty had detected the problem early and did not yet have an infestation, 17th century furniture was disassembled and tapestries and rugs were frozen to kill moths, larvae and eggs.

“Light, insects, humidity and temperature are the most egregious things that cause damage to the art,” said Jane Bassett, the Getty’s senior conservator for decorative arts. “So it was looking at this as a preventive step.”

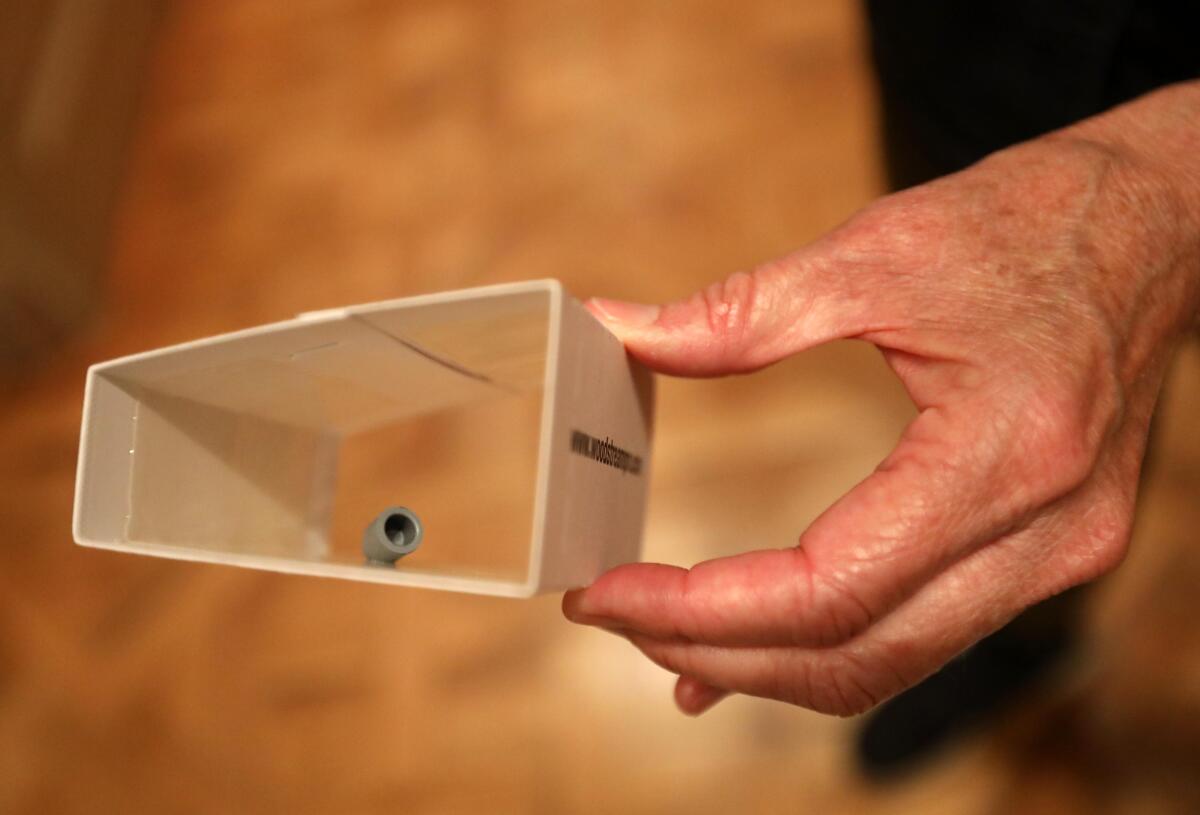

The Getty noticed the moth uptick in mid-April 2020. It has “zero tolerance” for pests, Bassett said, and typically has about 55 moth traps scattered around the museum for detection purposes, placed in locations such as storage rooms and galleries. They’re surprisingly low-tech tools to be wielded by one of the world’s wealthiest museums: cardboard sticky traps not unlike a roach motel. Some of them include female clothes moth pheromones to lure the insects.

Madeline Corona, assistant conservator of decorative arts and sculpture — whom Getty colleagues nicknamed “the pest maven” during its battle on bugs — makes weekly rounds, checking all the traps. In pre-pandemic times, she would typically see one or two moths every few weeks or months. In April last year, she began repeatedly seeing a few moths in one of the galleries, near an 18th century, pink silk upholstered bed. That number rose to 20 moths in another decorative arts gallery.

The museum’s security staffers, in addition to monitoring visitor behavior and preventing damage to artworks, are trained to keep an eye out for moths and other pests — and to alert conservators of the unwanted guests. With security staff reduced, the uptick went unnoticed in many places.

“I was definitely concerned,” Corona said. “But this is why we have an integrated pest management plan in place. We were ready for pests!”

MOCA senior curator Mia Locks resigned after nearly two years on the job. The museum’s HR director, Carlos Viramontes, quit in February. Viramontes cited a “hostile” culture at the museum.

Enter: Project Moth Remediation, for which a fleet of workers at the museum was mobilized to clear the galleries of insects and to fend off future ones. “It was us noticing a trend and getting ahead of it before it became a problem,” Corona said.

“Moth remediation” is a fancy way of saying “deep cleaning” to remove not only the insects, but also their food, a primary source of which is dust. Dust — prepare for the ick factor! — is made of bits of clothing fibers, food, human skin and other matter that accumulates in cracks and crevices. So work crews descended on one gallery at a time with specialized tools such as a micro spatula and a high-powered vacuum — the latter of which has the ability to “suck softly” on delicate surfaces, Bassett said.

The floors alone took a week to clean in each gallery. The workers sliced through cracks in the parquet floorboards with what looks like a letter opener, then sucked up the debris.

“We had to pick the dust out of every crack, between every piece of wood,” said Getty lead preparator Michael Mitchell, who oversaw the cleaning crews and deinstallation of artworks in the galleries. “We had crews of four people on their hands and knees with vacuums and dental picks and little, tiny brushes cleaning.”

Because the Getty’s galleries are connected by hallways, deep cleaning extended to the entire museum — 55 galleries in all. Paintings were removed and their backs, fronts and frames were gently dusted and the walls vacuumed. The cleaning in the 16 decorative arts galleries was still more intensive.

Twelve tapestries were gingerly vacuumed using a brush with a natural bristle head before being deinstalled with ropes and pulleys; then they were carefully rolled so as to prevent puckering and tension. Then they were frozen in batches of four, at minus-20 degrees Fahrenheit, in a trailer on campus for 10 days at a time. As the rest of Los Angeles was quarantining its groceries in the garage, the Getty was quarantining its textiles.

The textile works — including two 18th century French screens, a hand-knotted wool and linen carpet woven in the 1660s, and the 17th century wool and silk tapestry “Le Cheval Rayé” from the “Les Anciennes Indes” series” — typically took several workers an entire day each to clean, transfer and position in the truck. They were wrapped with polyester quilting for loft, followed by layers of muslin to absorb moisture and sealed in plastic to prevent condensation. Then they were suspended on cradles in the truck, to reduce weight on the fibers.

Workers removing tobacco tar and dirt from the ceiling of L.A.’s Union Station were surprised to discover vibrant floral painting hidden for decades.

One of the most difficult tasks was disassembling furniture. The museum’s 17th century Boulle Cabinet, likely a royal gift to Louis XIV and considered one of the most beloved objects at the Getty, took three days to take apart and clean. It has an incredibly complex steel, wood and Plexiglas earthquake mount securing it to the wall and floor. The cabinet was then taken apart, which had been done only once before, about 10 years ago, for a technical study. Many of the furniture pieces had to be opened up with special keys — themselves kept under lock and key — in order to access the earthquake mounts.

“It’s a couple days’ process just to remove these pieces, clean all the components, then a couple of days to put it back together,” Mitchell said. “Then multiply that by the objects around the room.”

Taking apart the objects, Mitchell added, had a silver lining: “It sounds corny, but you get to be intimate with the objects,” he said. “We get to walk past them all the time but to actually see the insides of the cabinets, to figure out how it’s put together, to talk to the curators and conservators about it, it’s stimulating.”

To dust, workers used brushes with no metal, such as Japanese and Chinese paintbrushes with sheep, squirrel and goat hair.

Of course, while the museum closure created an opportunity for deep cleaning, the pandemic also made that task more challenging. Smaller crews wearing cumbersome PPE — including powered hard hats with forced-air ventilation — worked on alternate weeks, and progress was slow.

“It was a paradox,” Bassett said of the pandemic, resulting in a process that “might’ve taken three times as long.”

The moth remediation is mostly complete but for about a week’s work left. Rugs and tapestries are being reinstalled, and the Getty Center aims to open in late May, though it hasn’t committed to a date.

Having deep-cleaned the galleries, the museum can stay ahead of the problem, Bassett said. With the dust gone for now, the galleries are a less appetizing destination for moths. The galleries are also no longer dark, even with the museum still closed to the public.

At the start of the pandemic “we thought, ‘Oh, what a wonderful opportunity to save electricity and not expose things to light,’” Bassett said. “But these guys love hiding in the dark. So we’ve turned the lights on. We have them on our normal cycle now.”

The challenges of the months-long cleaning, Bassett said, paid off in educational value.

“We learned a lot about the museum and the collections,” she said. “Not all of us were here when we installed the museum. So now we are all up to speed, together, in understanding the dec arts galleries and collections more than had the pandemic not come.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.