Los Angeles Central Library’s map librarian Glen Creason takes a new route: retirement

- Share via

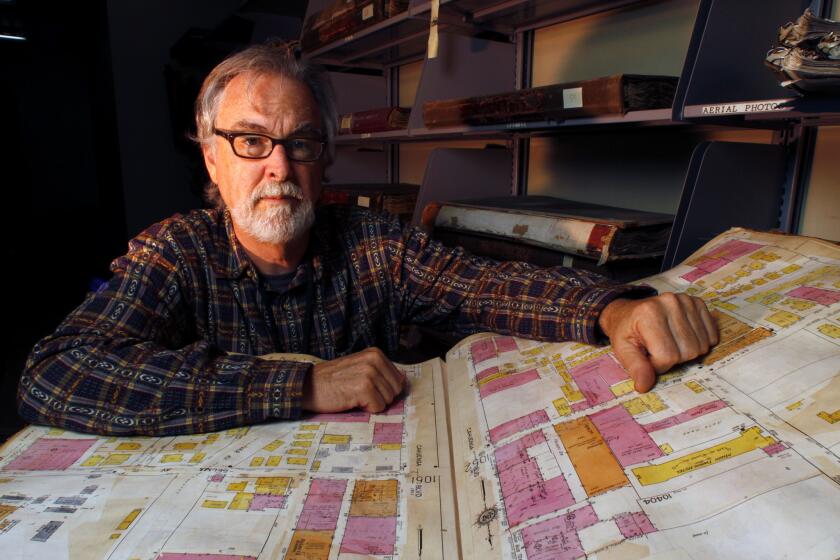

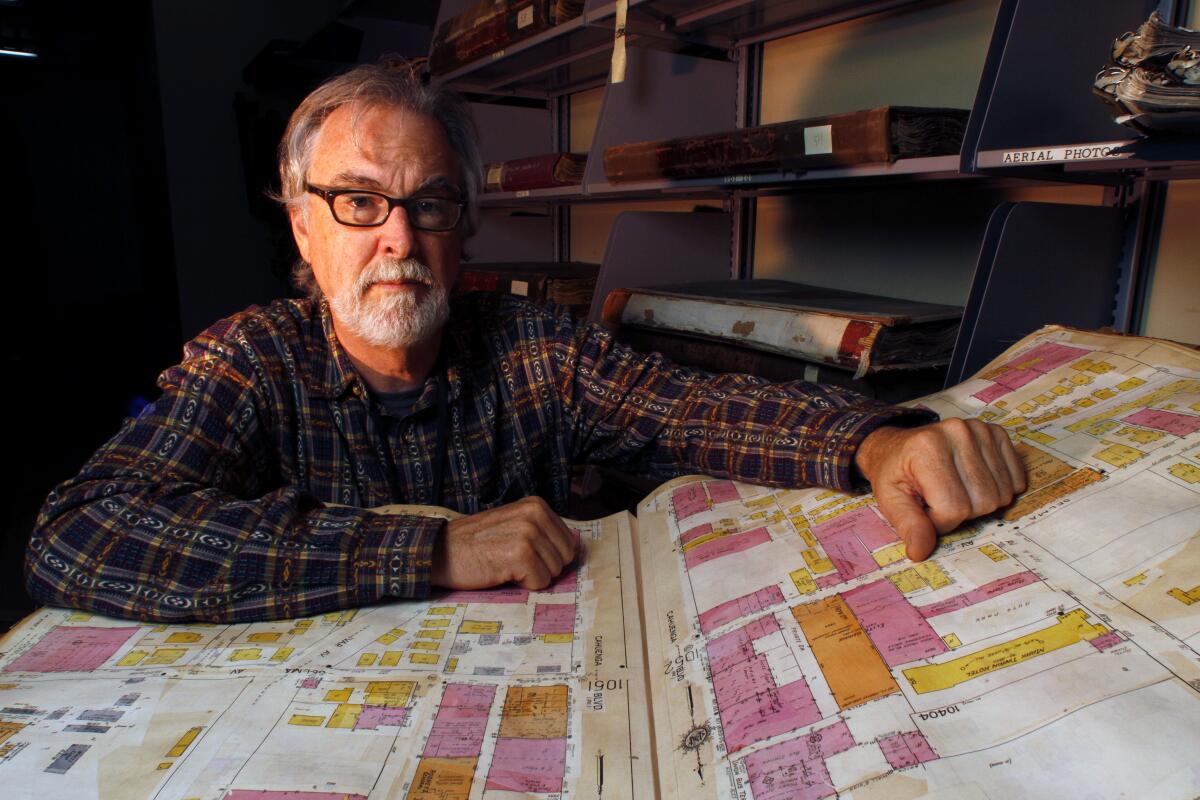

“I feel like I’m having a psychedelic experience,” says Glen Creason, the map librarian at the Central Library in downtown Los Angeles who is retiring after 42 years behind the desk. Friday was his last day.

Bearded and bespectacled just as he was when he started, Creason’s relaxed demeanor hides the fact that it’s a bittersweet prospect.

“I look forward to being able to do what I like, but on the other hand, this is my family here.”

His colleagues seem shocked too, said Creason, 74, who admits he tears up at television commercials. He wondered how he was going to make it through the going-away party, held Thursday night.

Jimmy Carter was president when the longtime resident of Glassell Park began work as a reference librarian. Creason describes himself as one of the last “hard copy” librarians, who answered questions by referring to books, and used typed catalog cards, a rotary phone and had a whole vocabulary known only to them.

“In 1989 the position working with maps was open, and it was more money, so I thought, ‘What the hell?’ And I knew nothing about maps,” he says, laughing.

A map librarian researches, gathers and catalogs material for the collection and responds to requests from patrons. With no experience, Creason had to go to collections at UCLA, the Seaver Center and the Huntington, “on bended knee,” to learn.

He says his epiphany came when he thumbed through some pictorial maps.

“I thought: ‘Now we’re talking. This is something I can get into.’”

For the last couple of years, Los Angeles Public Library map librarian Glen Creason has been involved in one of the most interesting literary projects in Southern California: to write each week, on the Citythink blog of Los Angeles magazine, about a map from the library’s collection.

Creason almost retired in 2015 when he said he was “completely lost for six months” due to some mental health problems, but the support of the library helped him through. So did the John Feathers Collection.

Containing thousands of items, the collection was donated in 2012 when the real estate agent of a large home on a ravine in Mount Washington said the library could take what it wished. Creason gets a similar call about once a month and sometimes he finds treasure, like Disneyland maps or a 1932 Olympics map. A thrift store in Temple City also keeps an eye out for him.

“Anything pictorial about L.A., my assigned specialist area, we put in our collection,” he says. “But this? It was absolutely mind-boggling. Even recently, the new owner found four more boxes of maps under the floorboards.”

He recently finished cataloging the huge number of Feathers’ California-related items, which included “a complete set of Thomas Guides, which even the company didn’t have, Rennie Guides, Gillespie Guides going back to the 1920s, fold-out maps, road atlases from before we had a highway system, travelogues, a four-volume set about soils in Iowa. I even found his library card and driving license.”

Even after finding such treasure, it was the COVID-19 pandemic that made him finally decide to retire.

“Even telecommuting, I was at home for over a year and trying to fill up my days,” he says. “I think I developed a kind of Zen appreciation for it, my two cats, my daughter and my family.”

He looks out at the many empty chairs in the History & Genealogy Department.

“And when the library reopened, it was sort of a letdown. We like to help people find answers, that’s what’s fun for us, but people didn’t come back in the ways we thought.”

He already has several large plastic tubs filled for his departure, but can’t face dismantling his cubicle yet: Every inch of the gray walls is covered with newspaper clippings, cartoons, pictures, Dodgers memorabilia and more.

Creason recalls the famous — and infamous — people he has met at library events, or ones who came to his desk for help. He mentions actors Diane Keaton and Denzel Washington, novelist Susan Orlean, chess legend Bobby Fischer, actor Peter Falk and a Yale freshman called Jodie Foster.

“She knew everything before she arrived,” says Creason admiringly.

A committed Anglophile whose mother was from Northumberland in England, Creason says it was a special thrill when he met Sherlock Holmes actor Jeremy Brett, who was researching for a role as an explorer. He has also written about his chillingly brief encounter with Richard Ramirez, the “Night Stalker” serial killer, who asked for books on torture and the occult.

Everyday patrons could be challenging too.

“There was a former math teacher from Wisconsin who had lost his mind somehow. He would ask for a pair of scissors, then lean over a trash can and cut his hair and beard. One day he left a scrap of paper with ‘You get smarter and smarter’ written on it. He meant people generally, and I framed it and put it on my wall at home.”

He did, however, receive his share of impatience, disbelief and even abuse.

“People insist they know who killed the Black Dahlia, or the Kennedys, and I’ve been asked for the map of 15th century Iran that showed where the treasures are buried, for Nazi tarot cards and for maps of the secret downtown tunnels. Bootleggers wouldn’t have kept a map of them!”

How did the L.A. Public Library help launch poet Amanda Gorman and teen punk group the Linda Lindas into the world?

As for the strangest thing he’s come across, Creason recalls that when the library was moving back from its temporary location following the April 1986 arson that saw 400,000 volumes burned, something was stuck in the back of a map drawer.

“It was a mourning ribbon worn when Lincoln’s funeral train came by.”

After grumbling that the map collection doesn’t have a working, professional scanner — “Boston and New York Public (libraries) have thousands of maps digitized, and we have about 70 — It’s a disgrace” — he returns quietly to thoughts of his imminent departure.

“It just seemed to go,” he snaps his fingers, “like that.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.