Bad guys in banking movies are usually noisy. ‘Azor’ shows the horrors of silence.

- Share via

In the sly new finance movie “Azor,” a Swiss banker named Yvan de Wiel is visiting Argentina in 1980 on business, but the military dictatorship’s “dirty war” against its political opponents keeps slithering up around him. In an opening scene, De Wiel watches quietly as soldiers detain two young men on the street. After the camera cuts away and returns, only one young man remains, his partner joining the ranks of Argentina’s thousands of desaparecidos. “You don’t have to worry,” the banker’s driver reassures De Wiel; they’re in a Swiss Embassy vehicle, shrouded in diplomatic and moral immunity.

A soldier waves the car through, and De Wiel — whose own Swiss partner has also gone inexplicably missing — is off to reassure his jittery, ultrarich Argentinian clients that their money and their secrets are safe. But unlike many movies about the impunity of the 1%, the elite of “Azor” are homebound, paranoid and scared to speak the truth above the volume of a whisper. Their polite Swiss banker can’t protect them from a gangster government that kidnaps their racehorses and their heirs with leftist tendencies. “They’re chasing us like rabbits,” a matriarch tells De Wiel the first moment she’s sure she won’t be overheard.

While De Wiel visits the wealthy’s sitting rooms, swimming pools and exclusive clubs, the nation’s violence stays off-screen, but the dread never leaves the frame. Not least because it’s unclear where a banker’s loyalties might lie when the military suddenly has an “El Dorado” of seized assets that only someone with French cuffs and a Swiss passport can easily liquidate. The film’s title is a banking codeword for “be quiet, careful what you say,” and the story prefers the horrors of the unsaid.

Andreas Fontana’s moody political thriller ‘Azor’ mines the murky world of finance during a junta in Argentina.

American viewers will find that “Azor” — the first feature-length film by Swiss director Andreas Fontana, now streaming on Mubi — is a minimalist departure from U.S. movies about high finance, which can’t help but explain themselves, usually loudly. In Oliver Stone’s 1987 “Wall Street,” financier Gordon Gekko’s iconic “greed is good” speech summarized the intellectual status of a decade of deregulation, junk bonds, leveraged buyouts and retreats by organized labor. Martin Scorsese’s “Wolf of Wall Street” (2013) drinks Champagne from the same Reagan era flute. “I want you to deal with your problems by becoming rich,” Leonardo DiCaprio’s Jordan Belfort exhorts a mob of ecstatic traders.

In 2011’s “Margin Call,” which depicts the start of the 2008 financial crisis, a midlevel trader played by Paul Bettany unapologetically rails against the John Q. Publics who had been happy with Wall Street’s toxic adjustable-rate mortgages when it meant bigger houses and fatter 401(k) accounts for the little guy. “They want what we have to give them, but they also want to play innocent and pretend they have no idea where it came from,” he complains from his convertible. When the antiheroes are running things, they get to give the speeches.

More recent Hollywood treatments of the finance world have become didactic to the point of agitprop, coinciding with a realignment of American politics in which Republicans have gotten more trade-protectionist and young people more socialist. To help dramatize the planet’s absurdly complex 2008 financial crisis for his 2015 film “The Big Short,” Adam McKay cast Margot Robbie to sit in a bubble bath, sip Champagne and break the fourth wall to explain mortgage-backed securities directly to viewers. Steven Soderbergh’s 2019 movie “The Laundromat” borrowed the same device for Antonio Banderas and Gary Oldman, who wore garish tuxedos as they let audiences in on the secrets of global offshore banking. It’s art about capital that desperately hopes you’re getting the message.

“Azor” skips the narrative tricks and sticks to the less macho world of Swiss private banking, where families often run banks that are handed down from generation to generation. “It’s a very specific milieu, quite powerful and discreet,” Fontana says. Fontana’s grandfather had been a banker, and Fontana was fascinated by a posthumous diary entry about a 1980 visit to Argentina that never mentioned the political situation unfolding “in the off-screen of the notebook.” (It did mention the American election of Ronald Reagan to the presidency.)

Fontana decided the script — which, he stresses, is not biographical — should similarly “show only the very strictly necessary things, and all the rest, to let the audience imagine it.” He strove to be sociologically “accurate” to the environment, casting the picture’s Argentinian characters with nonprofessional actors from the country’s real-life elite. “The director of casting called me the snake charmer,” Fontana says of the recruiting process. “If I was a journalist, I’m sure they would not have been working on this project.”

The film’s main character, De Wiel, played by actor Fabrizio Rongione, has inherited a bank and a large house in Geneva from his father, but De Wiel seems to lack the charm, the awareness and the cunning of his missing partner Keys, who disappeared shortly after investigating a prospective client nicknamed “Lázaro.” While the bank is De Wiel’s patrimony, it’s his wife, Inès (played by Stéphanie Cléau), who’s the real brains of the operation. Their marriage, and its gendered imbalances, are the film’s other major subsurface conflict.

Inès can read a room better than her husband, can put people more at ease, and therefore must constantly explain to him what’s actually happening. She knows which jackets her husband needs to wear to make his shoulders look more imposing. “My husband and I are one and the same person — him,” Inès confides to a female client. After she’s blocked from joining a meeting at a racetrack because of her gender, and her husband meets and loses a client, she bristles at his ineffectiveness. “Your father was right,” she tells him. “Fear makes you mediocre.”

As with many finance movies, “Azor” is ultimately a success story more than a hero’s journey. De Wiel abandons the country estates and the hotel swimming pools where he’s comfortable for a journey into the wilderness, where even his fellow Swiss transactioneers have been afraid to go. “War is won on the front,” one sinister client, a pro-junta priest with a penchant for speculating on foreign currencies, reminds De Wiel before the trip. The film’s conclusion tells an even bleaker story about Swiss private finance than most American movies do about Wall Street.

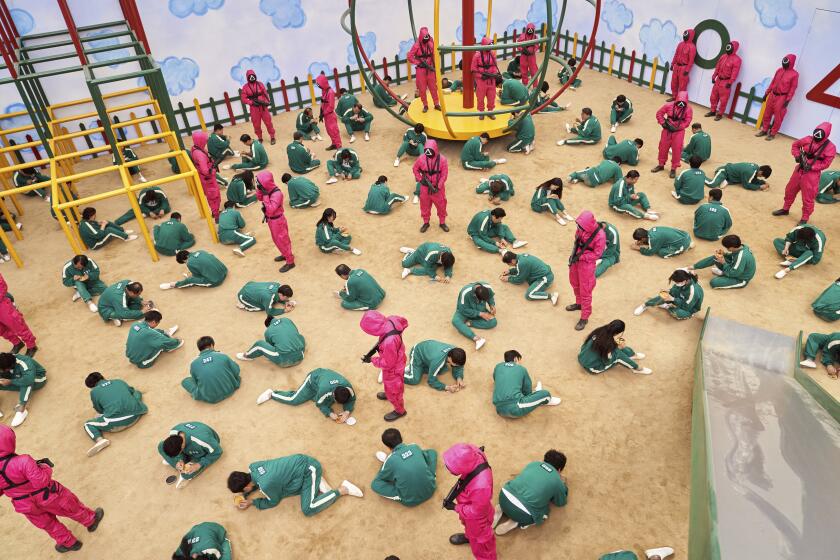

A reality show pro breaks down MrBeast’s viral redo of Netflix’s “Squid Game” as a YouTube video with real-life contestants. We figure it cost about $134,600 per minute to make.

After giving an interview with The Times for this story, Fontana reflected on his research process in a follow-up email. “You should know that I met about ten private bankers during my research, and among them, one has since committed suicide, and the other has disappeared, nobody knows what happened to him,” Fontana says. “It’s a milieu without oxygen, without love even, I would say.” In Geneva, Fontana says, there’s a local saying “that the children of bankers, when they are not bankers themselves, are artists or junkies.” He adds, “It’s a terrible phrase.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.