Andrea Bowers’ activist art has long been a conduit for hope — and still is today

- Share via

Friday, June 24, was supposed to be a celebratory day for artist Andrea Bowers. Her Highland Park home was filled with friends visiting from afar; all of them were in town to join her that evening at the Hammer Museum’s opening night party for “Andrea Bowers,” a retrospective featuring more than two decades of her work.

“There was this joy in my house [that morning],” Bowers recalls. But then news broke that the Supreme Court had overturned Roe vs. Wade. Joy was instantly replaced with grief.

Talking about that morning a little over a week later, Bowers’ voice cracks and her eyes brim with tears. “It felt like somebody dropped a giant boulder on my body,” she says. “There was this deep sadness in my heart. I didn’t want to have the opening. All I could think about were Pat [Maginnis] and Lana [Phelan], the women I met, all the risks they took, generations of hard work by activists erased.”

In 1964, Maginnis, Phelan and Rowena Gurner founded the organization that would become the advocacy group NARAL Pro-Choice America. Before the passage of Roe vs. Wade in 1973, the Bay Area trio, often dubbed “The Army of Three,” fought for people to gain access to legal abortions and helped them connect with doctors in Mexico and Japan who could terminate their pregnancies safely. Their work — along with the words of the many desperate people who sought their aid — is the subject of Bowers’ 2005 video piece, “Letters to an Army of Three.”

That video, along with an accompanying installation, inhabits a large corner in the first of three galleries currently dedicated to Bowers’ work at the Hammer. Rather than flowing chronologically, the retrospective is presented thematically, with each gallery featuring artwork inspired by a unique facet of activism.

When you enter the first gallery, you’re greeted immediately by a big, blinking yellow and red neon sign that reads, “My Body My Choice Her Body Her Choice.” It’s a bright, straightforward statement introducing a gallery filled with overtly feminist artwork, including the eye-catching, large-scale acrylic-marker-on-cardboard piece from 2020 titled “Can You Think of Any Laws that Give Government the Power to Make Decisions About the Male Body? Quote by Kamala Harris During Brett Kavanaugh’s Confirmation Hearing in 2018” and tiny, more intimate drawings of anonymous protesters rendered in patient and loving detail.

Hammer curator Connie Butler, who organized the show in collaboration with curator Michael Darling and the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, says that while she never could’ve anticipated the show’s opening coinciding so precisely with Roe’s reversal, the decision to open the retrospective with a bold feminist statement was always purposeful.

“We knew that Roe was on the Supreme Court’s docket,” Butler says. Regardless of contemporary politics, she adds, “Feminist issues [and] reproductive rights are really important to Andrea, and one of her central concerns for the last 20 years.”

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, when Maginnis, Phelan and Gurner were busy fighting on the frontlines for reproductive rights in California, Bowers was a little girl growing up in small-town Ohio. In her early 20s, she moved to Manhattan “because all these famous New Yorkers were on the covers of magazines, and I thought I’d just move there too,” she says with a laugh. She ended up in Hoboken, N.J., before abandoning her New York dreams for California ones.

Bowers moved west in 1990 to attend the California Institute of the Arts in Santa Clarita. She was in her mid-20s and her mind was a sponge, soaking up esoteric artistic theories about Conceptualism from artists like Charles Gaines and studying feminist art history with mentors like Suzanne Lacy. Later that decade, Bowers, now 57, bought the Highland Park home she lives in today and settled into life as an Angeleno. Today she is a prominent fixture in the L.A. art scene, where she teaches in the graduate program at Otis College of Art and Design and maintains dedicated activist and artistic practices.

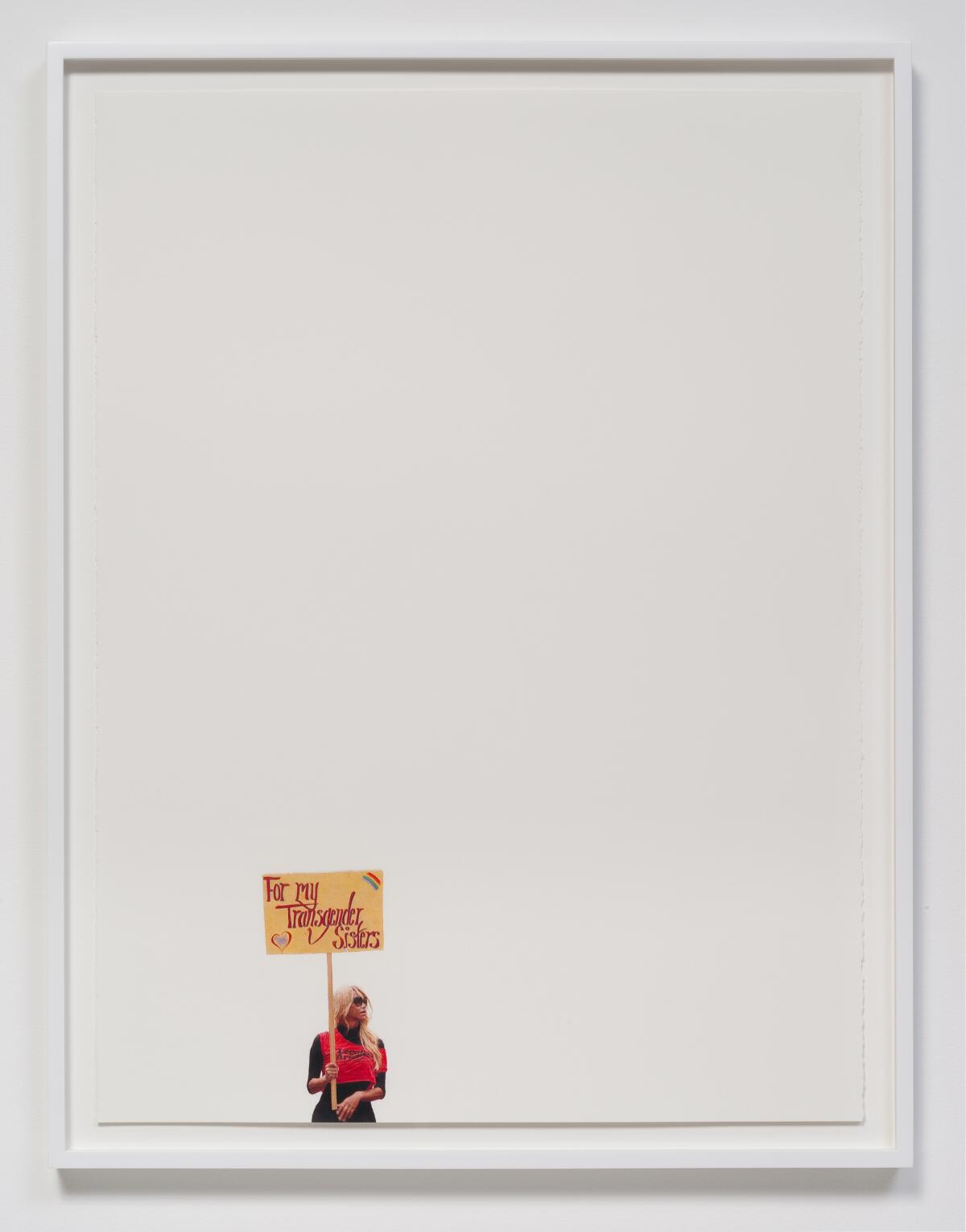

For Bowers, activism and art are inseparable. In her day-to-day life, she works with activist groups that promote environmental, immigration and trans rights, all of which feature heavily in the Hammer show. In the gallery focused on environmental activism, one miniature drawing is a self-portrait — a detailed replica of a mug shot, a token from an eco-activism-related arrest.

When asked about her artwork, Bowers frequently pivots to talking about the activists who inspire the work (and her). A conversation about photography turns into a conversation about the TransLatin@ Coalition. “If they could run our government, it would be a beautiful place,” she says.

Throughout the Hammer show, ephemera from progressive movements is presented alongside videos and sculptures that document and honor activists’ work. Bowers describes these pieces as “bearing witness.”

“Some of those videos are both aesthetic and practical training videos,” she says. “If you actually sit and listen to them, you’re trained in nonviolent civil disobedience. You’re actually trained in tree-sitting if you want to be.”

A 25-year survey of the L.A. artist speaks to our conflicted moment.

Works like “Letters to an Army of Three” do more than document history. They inform the present. One note featured in the work, dated Feb. 12, 1968, concerns a woman from Santa Ana seeking information on how to obtain an illegal abortion, writing, “Thank you for just reading this — please want to help me. I just can’t go on like this!”

The stationery is faded, but the distress within it feels immediate and contemporary, as if it could have been typed in an email today.

The reality that pleas like these are still so relevant can be wrenching. “I cry a lot. It’s so emotional to bear witness to all of those stories,” Bowers says.

But there’s no room for nihilism in Bowers’ worldview. On the day that Roe was overturned, after she cried with her friends, Bowers decided to move forward with the night’s planned festivities. “No matter all the grief, all the pain, all the talk of moving to different countries. These [activists] have taught me you just can’t give up,” she says.

And the mood at the Hammer on opening night? “I would say that we danced a little,” Butler says. “People felt like there was hope in [Bowers’] work, that as dark as the days are, there is a feeling of persistence there.”

'Andrea Bowers'

Where: UCLA Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd., Westwood

When: Closed Mondays. Tuesdays through Sundays 11 a.m.-6 p.m. Through Sept. 4

Info: (310) 443-7000, hammer.ucla.edu

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.