Review: In a must-see L.A. show, painter Bob Thompson uses art history to consider social injustice

At three-feet-square, “The Circus” isn’t the largest painting in the deeply absorbing survey of Bob Thompson’s brief but intensely productive career. (He died in 1966, a month shy of his 29th birthday.) Often, as the newly opened survey of 50 paintings at the UCLA Hammer Museum indicates, he worked large, and sometimes at almost mural scale.

But “The Circus,” painted in 1963 when Thompson was living on the bohemian island of Ibiza in the Mediterranean Sea off the coast of Spain, is formally hypnotizing and conceptually disconcerting despite its easel-size. The composition was inspired by Francisco de Goya’s renowned, politically trenchant aquatint, “The sleep of reason produces monsters.” As a Black man raised in the American South, Thompson knew all about the irrational nature of feeling and the monstrousness it could generate.

What he did with that knowledge is surprising.

In the painting, enormous, swooping silhouettes of owlish birds, one green and the other blue, each with wings spread wide, are creatures that display both menace and freedom. They are being grappled by two muscular, slightly crouching figures, one crimson and the other bright yellow. Whether the birds or the figures are on the attack or escaping is hard to say.

A second skirmish is also underway. Thompson’s chosen palette is dominated by flat planes of primary colors. The human and avian forms yield a vivid sense of socially and culturally approved Modernist abstraction struggling against an unquenchable, if unfashionable, urge toward figurative painting. Thompson uses Goya, a hinge between Old Master and Modern art, to ruminate on an up-to-the-minute artistic debate.

Below the wrestling men and birds, a small, rudimentary figure is hunched at a table, head down, like Goya’s dreaming man. In the Spanish artist’s famous 1799 etching, owls and bats swarm around the dreamer’s recumbent body, nocturnal nightmares staring straight ahead with fierce attention directed at the viewer looking in on the scene. Goya’s private, internalized fears are externalized, transforming into intimate, vaguely satirical spectacle.

Thompson does something different: His combatants are acting out on an open stage, as if in the ring. They’re poised between the imagining artist out front and a boisterous crowd of onlookers, rudimentarily sketched out as a wall of people looming in the background. A show is on.

Goya speaks to us one-on-one. But, appropriate to a mass-media age, Thompson speaks to us as part of the faceless crowd — or, in the worst case, the mob. The circus is an established modern metaphor of life’s social raucousness, which has been reconfigured into a scene greeted more with queasy entertainment value than with empathy and understanding.

Thompson, keenly attentive to his situation as a Black painter in a white-dominated society, including an art world largely closed to him, yet very much attuned to the social and cultural turmoil of the expanding civil rights movement in the early 1960s, presents a complex revision of Goya’s take on grinding immorality in his “Los Caprichos” suite of prints. “The Circus” didn’t make it into the impressive 1998 Thompson retrospective at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art — that’s not too surprising, since nearly a thousand works are known from his compact eight-year career — which brought the artist back to national attention three decades after his untimely death. Yet, today, as a national reckoning over racial inequities proceeds, the painting gains new relevance.

“Bob Thompson: This House Is Mine,” organized last year by the Colby College Museum of Art in Waterville, Maine, is a must-see exhibition concluding a four-city national tour. (Hammer curators Erin Christovale and Vanessa Arizmendi have overseen the installation.) The title comes from a tiny 1960 painting on board at the entry. The “house” over which the painter is taking possession is manifold: His identity as a person, his commitment to being an artist and, not least of all, the museum-affirmed legacy of Western painting newly claimed as an American inheritance in the years after the ruin of World War II.

That “house” is also mine, Thompson declared, regardless of who — white supremacist or Black nationalist — might say otherwise. The exhibition unfolds what that meant.

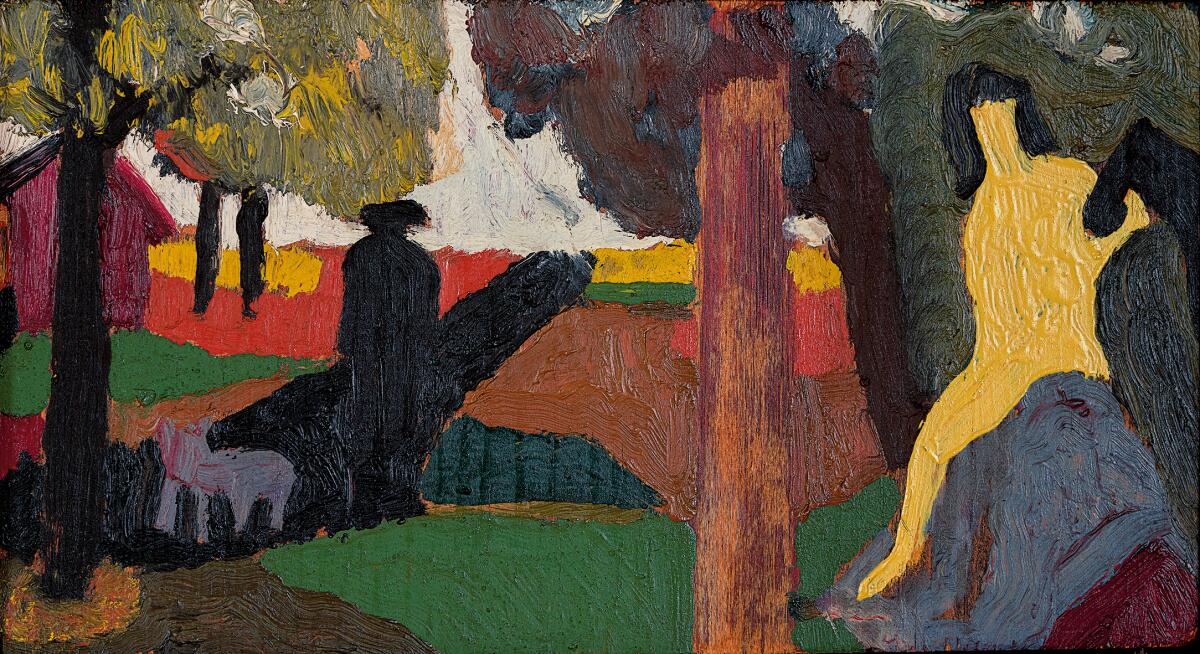

Individual paintings show him taking possession, reworking and reinterpreting a host of Renaissance and Baroque precedents, just as he did with Goya and “The Circus,” to make something distinctive and new. European paintings by Lucas Cranach the Elder, Fra Angelico, Piero della Francesca, Tintoretto, Rembrandt, Nicolas Poussin and other artists in the Western canon echo in his work, submerged within Modernist forms. (Think Matisse and German Expressionism, especially.) Black artists of a prior generation like Romare Bearden are influential as well, along with inspiration from jazz musicians such as Nina Simone and Ornette Coleman.

Western art history is overrun with themes like bodily violence and spiritual transcendence, and they find resonance in African American life. Thompson looks them in the eye.

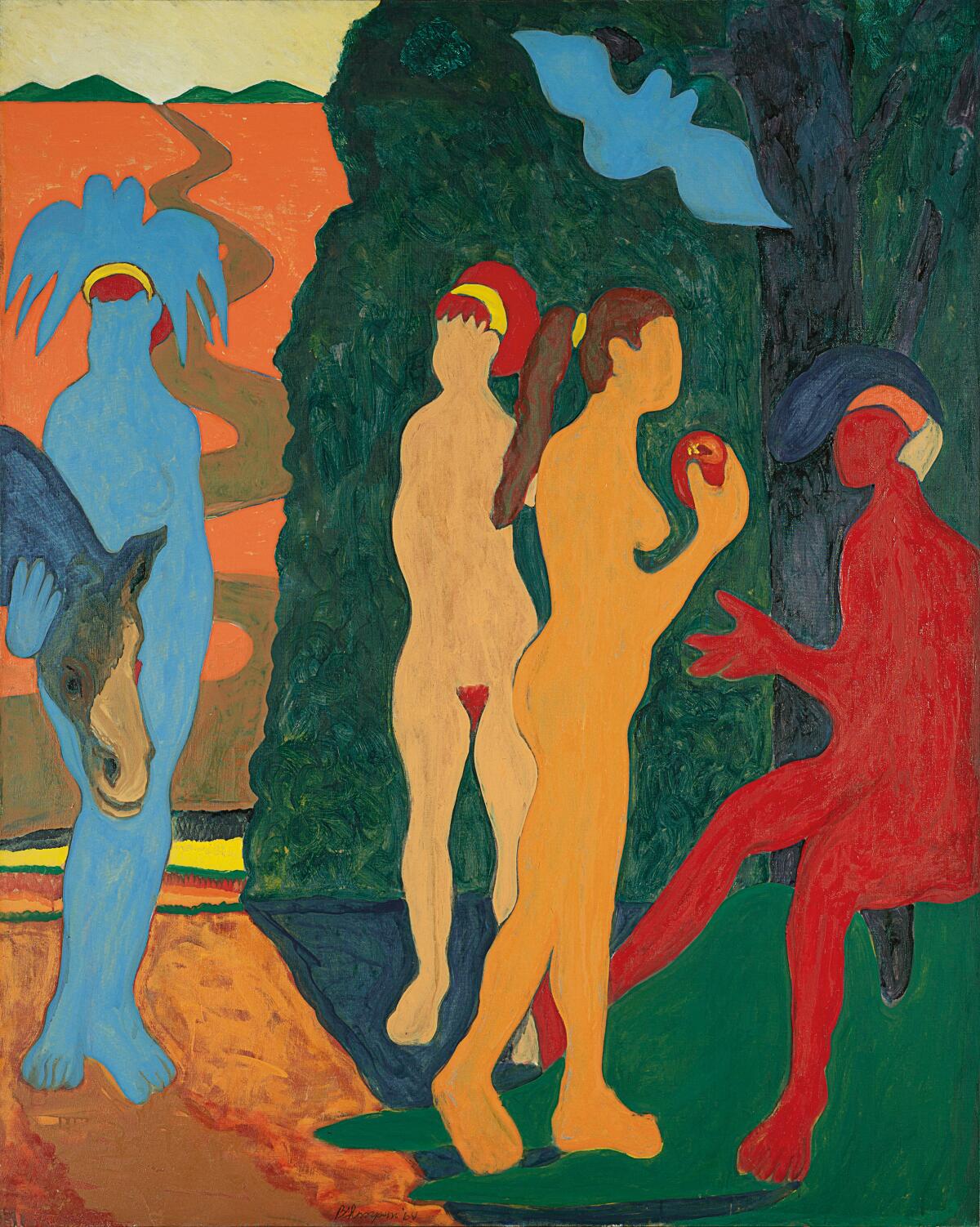

And he asks questions about his own life as an artist. More than once he painted “The Judgement of Paris,” the Greek myth of personal affront and backroom bribery that erupted into the epic Trojan War. An inquiry into cultural beauty standards also surely doubles as scrutiny of his reception in Paris, the centuries-old artistic capital of France.

Thompson was born in Louisville, Ky., deep into the Great Depression and a few short months after the Ohio River famously flooded the city, cresting at an astonishing 40 feet and putting more than two-thirds of it under water. The worst natural disaster in Louisville history no doubt played a role in the family’s decision to move to nearby Elizabethtown. His father, a dry cleaner, died in a car crash when Bob was 13, leaving his teacher-mother to raise three kids.

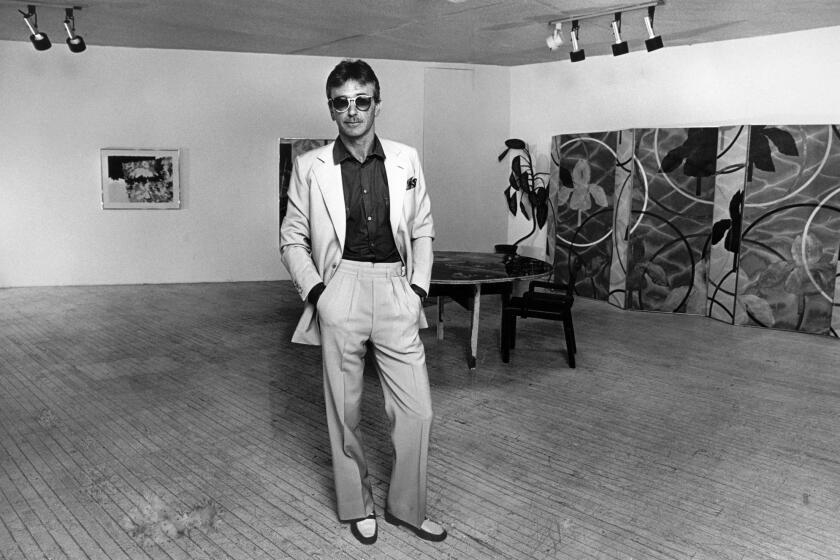

Billy Al Bengston, the artist and sculptor who helped establish the Ferus Gallery as a contemporary art hot spot in midcentury Los Angeles, has died.

A brief flirtation with pre-med studies at Boston University was followed by immersion in Louisville’s Hite Art Institute, where he answered a youthful call. Eventually he landed in New York, settling in bohemian neighborhoods of Greenwich Village and the Lower East Side. He was 21, and avant-garde art was at an inflection point. Abstract Expressionism had become the establishment and new directions were emerging. He left the city for the first of two extended stays in Europe.

The Hammer exhibition gives particular emphasis to two thematic moments. The first is to images of brutality, the second to an artist.

Crucifixions and the martyrdom of saints are pretty standard stuff in European art history. Thompson united the Christian image of the cross, a place of unspeakable suffering on the road to deliverance, with the gruesome specter of the lynching tree.

In one especially powerful example, a figure wielding a stick smeared with a slash of blood prepares to whack an amorphous black figure suspended from a tree limb, hanging above shattered bodies on the ground. Even more disturbing than the violence, which derives from a strangely sweet Fra Angelico panel of saints being beheaded that Thompson saw at Paris’ Louvre Museum, is the cluster of rudimentary figures looking on passively at the left.

They recall nothing so much as the placid white onlookers in horrible souvenir lynching photographs, here rendered in a multicolored array as a pleasantly flamboyant throng. A second organic black form kneels before them, taking a place in the lynching line.

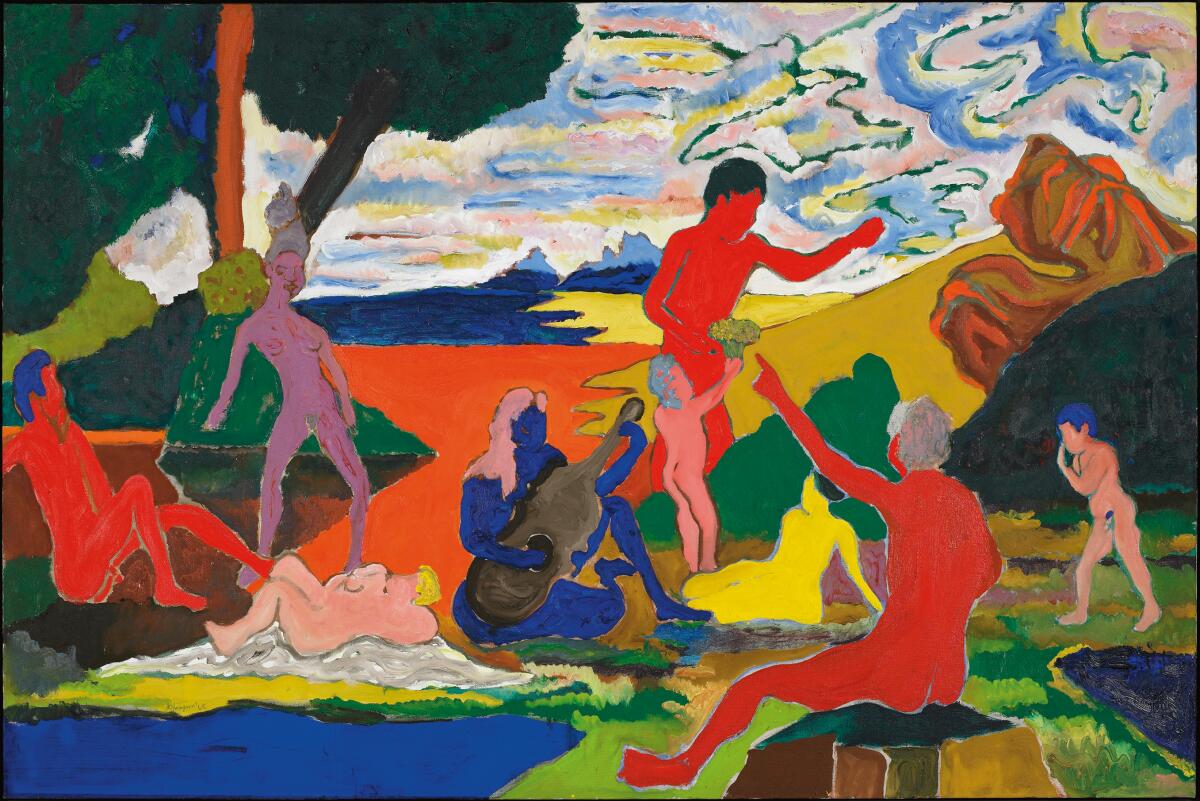

Poussin plays an outsize role in a number of major works that respond to the French Baroque classicist’s elaborate paintings, which are based on ancient religious and mythological stories. Appropriating the composition of Poussin’s “Bacchanal with Guitar Player,” for example, Thompson inserted singer Nina Simone, passionate icon of Black liberation, into the precisely ordered yet boisterous scene.

Thompson’s “Homage to Nina Simone,” just more than six feet wide, is slightly larger than Poussin’s painting. A willowy form brushed in a lavender hue, totally unlike the bold primary colors that describe the other revelers, Simone stands to one side and a few steps back. She assumes a cultural role as a lingering, ever-present spirit, different from all the rest.

Thompson may have felt a profound kinship with her as an artist — and with Poussin, too. Nearly half his working life was spent abroad. Poussin was French, but for more than 40 years he lived and worked in Rome, which is where Thompson decided to move in November 1965. Four months later, a heroin overdose after gallbladder surgery killed him. This inspiring show underlines how incalculable the loss was.

'Bob Thompson: This House is Mine'

Where: UCLA Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd., Westwood

When: Tuesday–Sunday: 11 a.m. – 6 p.m. Closed Monday. Through Jan. 8.

Info: (310) 443-7000, www.hammer.ucla.edu

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.