7 choreographers on how dance changed in Southern California in 2022

- Share via

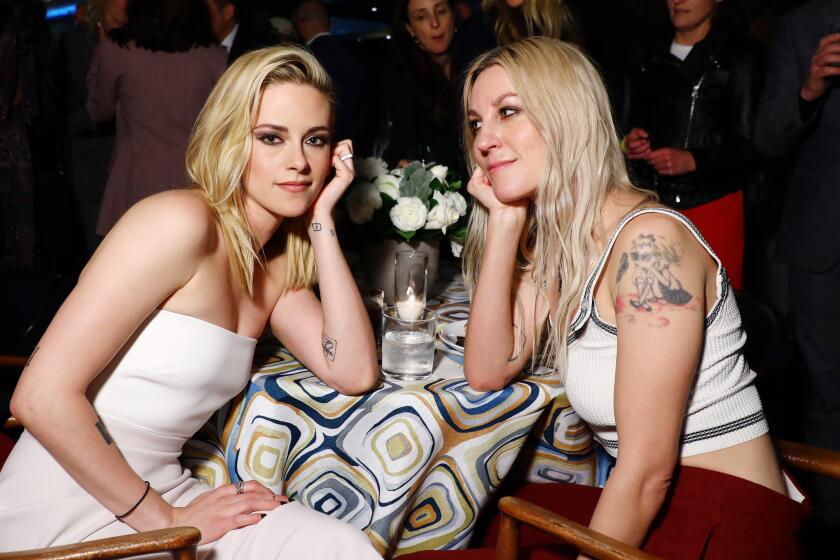

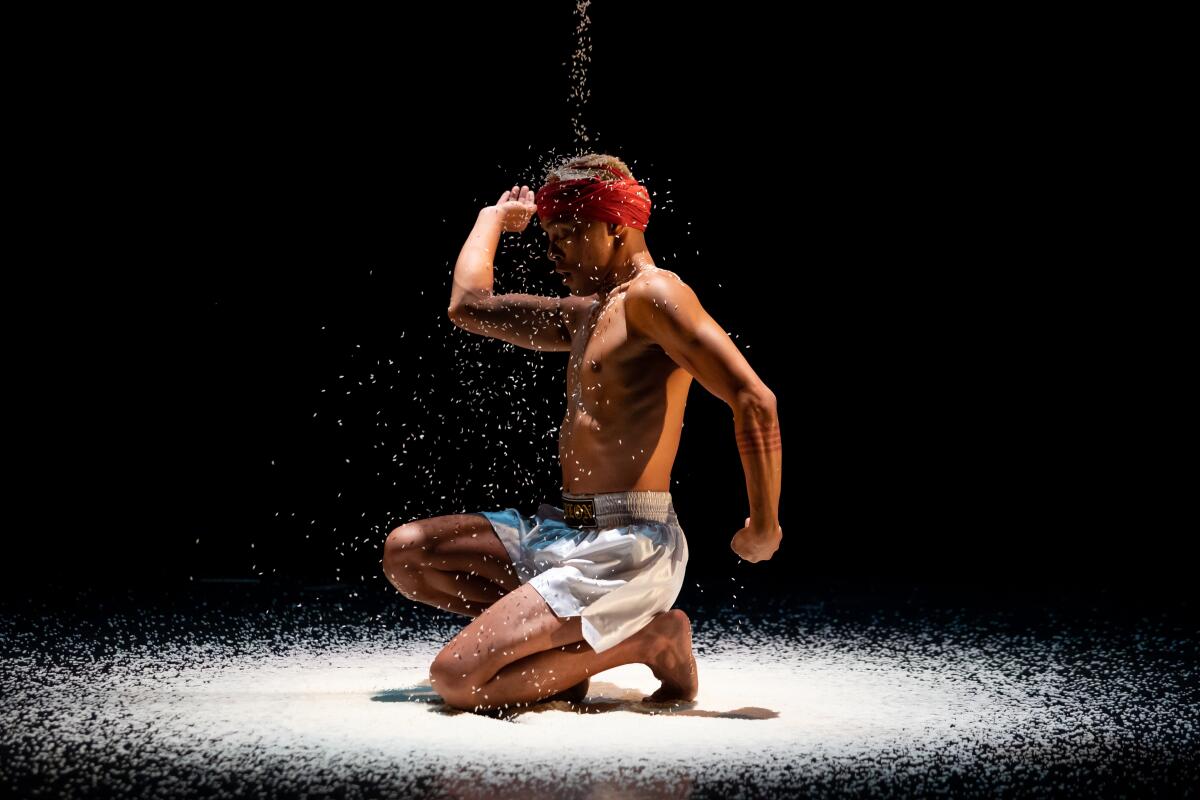

In June, the L.A. Contemporary Dance Company returned to the stage for the first time since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, presenting the world premiere of Roderick George’s “Dancing in Snow” at the Odyssey Theatre.

It was also the first show created by the company since Jamila Glass became its artistic director in 2021. The pause on live performances pushed Glass to “surrender to the emotions” that the experience conjured for her, specifically, the feeling of transition and the redefining of community.

She went on to direct and act as the supervising choreographer for the piece “and then life was beautiful,” with J.M. Rodriguez as associate choreographer and the company providing choreography contributions. The piece, which had its world premiere in November as part of the company’s “If These Walls Could Talk” program, conceptualized a fantasy she had growing up where she brought all her favorite people into a bubble where they could live freely. The fantasy ended up paralleling social distancing.

“It was very cathartic to allow that to unfold out of me, and it allowed me to create from a very honest place, rather than being concerned about what people might want to see,” she says.

Dancers and choreographers in Los Angeles and beyond made their return to stages throughout 2022 with new visions and a new sense of purpose. Choreographers found joy in moving with a community again. After experiencing the tolls of the pandemic — loss, stillness and uncertainty — the work of 2022 introduced new techniques, technologies and narratives that reflected the remnants of the pandemic and a new texture to Los Angeles dance.

While Glass found work in entertainment during the pandemic, choreographing for the final season of “Dear White People,” she says it could not compare to the “huge blank canvas” of the stage that welcomed dancers across L.A.

A time for reflection

The pause fueled Roderick George’s practice. “I found it the most therapeutic, because I was able to sit down and not feel like I was having to generate, because I think that’s something that’s happening in our culture is that we’re constantly generating material and having to present things as often as possible,” he says.

In “Dancing in Snow” for the L.A. Contemporary Dance Company, George was able to make movement that was more rigorous and specific. The piece zooms in on the 1950s to address cultural appropriation and capitalism in white America, toying with the phrase “Make America Great Again” under his own interpretation as a Black queer choreographer.

“What was important for me was to rattle bones and to rattle the emotions that we’re all collectively dealing with,” he says.

Jay Carlon also grew as a choreographer through reflections on spirituality and ritual. The pandemic brought on a new chapter as a solo artist for Carlon, who is an “avid contact improv artist” and relies on community. But the solitude of the pandemic made him look for closure in new ways.

“Over the pandemic, I experienced a lot of loss, and grief has come up a lot in my personal life,” Carlon says. “And so I was imagining how grief can be my partner, how grief can be my intimate partner, how grief can be my support and also my collaborator.”

He started to explore how dance could be used as a ritual to commune with his recent ancestors. He began the exploration in 2021 with “Baggage,” a dance film commissioned by Metro Art.

In August, Carlon presented “Novena,” an excerpt of his full-length work “Wake” premiering in 2023, at REDCAT as part of its New Works Festival. “Novena” is based on a Catholic ritual of the same name where you pray the rosary for nine days after someone dies. While he felt disconnected from Catholicism, he created the dance as a reimagining of the ritual to connect with his lola, or grandmother, who died in the Philippines. He says that there were parts of her that upheld white supremacy for survival and that through the work, he was able to dance with her to explore the feelings he could not reach through a Facebook live funeral.

“I imagined that I’m forgiving her, and there’s a sense of empathy and understanding,” he says. “I felt like I could do that through dance.”

Finding space

On the floor: Pedro Garcia, left, Jordyn Santiago and Ty Morrison.

At the beginning of the pandemic, Amadi “Baye” Washington and Sam “Asa” Pratt ventured into a new chapter of their career as a choreographic duo, shifting away from being performers. Prior to that, Pratt was on tour with the London-based Akram Khan Company. And Washington was performing “Sleep No More” in New York.

Creating in 2022 reminded them of the value of a performance space. In 2020, they were granted access to a vacant bank to create and rehearse. Later on, residencies like those with the 92nd Street Y and Baryshnikov Arts Center gave them the time and space to make works like “The One to Stay With,” which premiered in March at the Joyce Theater in New York with the L.A.-based dance company BodyTraffic. The piece had its West Coast premiere at the Wallis in Beverly Hills in October.

“Being granted residency space is absolutely pivotal to what you’re able to do,” Washington says. “Not only in terms of the movement you create, but how much you’re able to focus in that space, and then yield new modes of movement in invention and connection between each other.”

While Zoom made dance accessible, it was still difficult for choreographers to maneuver. “It’s something that we just had to deal with for a while,” Pratt says.

They also attribute their growth as choreographic partners to “Second Seed,” a dance film they started before the pandemic began as part of an ongoing series of work (live performance, film and discussion) that pulls from D.W. Griffith’s 1915 silent film “The Birth of a Nation” to explore white victimhood. It was released in March 2020 just after pandemic closures started.

A new mentality

Achinta S. McDaniel started developing “1947” in 2014. She visualized the piece as a dance based on the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, when India gained independence from the British. The performance implemented narratives and interviews from people who lived through it, including her grandparents.

When the USC Kaufman School of Dance asked McDaniel to set work on the first- and second-year students, she wanted to go against expectations and debuted “1947” at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts in April. She could tell the students were eager to talk about social issues, especially after the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 and the increase in anti-Asian hate crimes in the U.S.

“It was an educational experience for them to jump in and learn the history and the culture that took place, and then create an artistic work based on that,” she says.

The piece begins with a Bollywood performance but is quickly interrupted when a bomb goes off and a ringing sound slices the air. The joy of Bollywood is balanced by a poignant representation of the partition that is scored by interviews with those who lived through it.

In 2022, McDaniel has seen her career follow the same pattern, creating work that is joyful and poignant: In July, her dance company, Blue13, performed with composer A.R. Rahman, known for his Bollywood scores. And in August, McDaniel and her company created “Restless Autumn. Restless Spring” for the REDCAT New Original Works Festival.

In 2023, she hopes to continue “dismantling the monolith,” or break down the tendency to lump Asian identities together, and show audiences the expansiveness of the Asian American and Pacific Islander community through art. Namely, her new initiative, Play Date, provides stipends for AAPI choreographers and artists to create a work in progress and foster the community’s representation in the dance world.

“It feels like I don’t have to prove anything,” she says. “I can just feel in my own skin. I don’t have to prove that this is beautiful. The work speaks for itself.”

The same goes for Stephanie Zaletel. They still feel an “echo” of the pandemic. Before the pandemic, they were busy as a freelance artist and then immediately hit a halt with cancellations. They spent two years completing the certificate in somatic psychotherapy and practices program at Antioch University during the pause.

2022 marked a time of return to dance for Zaletel. They participated in the Loghaven artist residency in Knoxville, Tenn., and used the opportunity to road trip and explore their creative practice on their own. While traveling, they learned that they were accepted into the REDCAT NOW Festival.

Going back into rehearsal mode “was like breathing,” Zaletel says.

They created “5 Basic Movements (Vagus Excerpt)” for the festival, based on the five basic movements they learned about at Antioch University: reach, grab, push, pull and yield. “To be able to experiment with other dancers with this stuff was shocking after doing it alone for so long,” they say.

The pandemic allowed them to “shed,” no longer feeling like they had to invent everything. Zaletel feels as though their practice has taken a more authentic tone because there is a new value to moving with a community again.

“I’m just thankful to be in the room,” they say. “The outcome will be whatever the outcome is, but just to be with bodies doing this thing that I’ve committed my life to again — that’s all I want.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.