- Share via

It’s a Saturday at Black Market Flea, and activity is bustling in the vibrant, 125,000-square-foot space on East 60th Street off Central Avenue. Outside are lines of Black and brown people in their most expressive outfits, all pining to get in to the depot, which is filled with rows of vendor tents offering art, thrifted clothes or custom jewelry. Aromas float above the food trucks in the dining area, which is filled with people struggling to decide which cuisine they want to eat. Music is everywhere, coming from the DJ booth at the edge of the courtyard, pumped about the indoor/outdoor venue via multiple speaker setups.

Thomas Saunders, the founder of L.A. skate and apparel company Broke & Board, is no stranger to the event. Broke & Board has sold clothing and other items at the flea market since 2021, and for him, the people aren’t just consumers, they’re tastemakers who help shape future designs.

“We did a graphic called ‘Black power crunch,’ it’s a cereal box like Reese’s Puffs, but the peanut butter and chocolate cereal are little fists,” he said. “We just thought it was cool. But when we got the reception for it at the flea, we were like, ‘Oh man, we gotta do more of this.’ It definitely influences a little bit of the creativity process.”

The flea made a Saturday in January feel like summertime, for both vendors and attendees. People created their own dance floor in the courtyard by the DJ table, spinning in circles to the beat, while others splayed across the grass in the California sun.

“Feel free to dance, feel free to sit still,” the DJ called out over the mic. “Whatever you want, just don’t bother nobody.”

Once a month for much of the last year, this has been the scene at the Beehive, the energizing indoor/outdoor venue on Central Avenue buzzing with Black life. But the vitality lingers long after Black Market Flea’s vendors have packed up for the day.

The Tree Yoga Cooperative in the west wing offers yoga, meditation and other holistic wellness classes multiple times a day, centering Black and Latinx communities. Gallery 90220, founded by Compton native David Colbert Jr., hosts work from local artists on its walls. And South L.A. Brewery aims to open its doors later this year, delivering a Black-owned brewery and taproom to the community.

It’s a formidable lineup, and that doesn’t even include the technology and entrepreneurship center for kids in the community, or the festivals and one-off events that rent out the venue.

“Being from L.A., I’ve seen people getting punched out at the [Martin Luther] King [Day] parade,” Saunders said. “All these things that are supposed to be for us and by us for our prosperity, in the back of our mind, we think, ‘Something’s going to happen.’ But at the Beehive, it just has some type of energy. Even walking in there, the air feels fresher. I’ve never even seen nobody mad at their fellow man at the Beehive.”

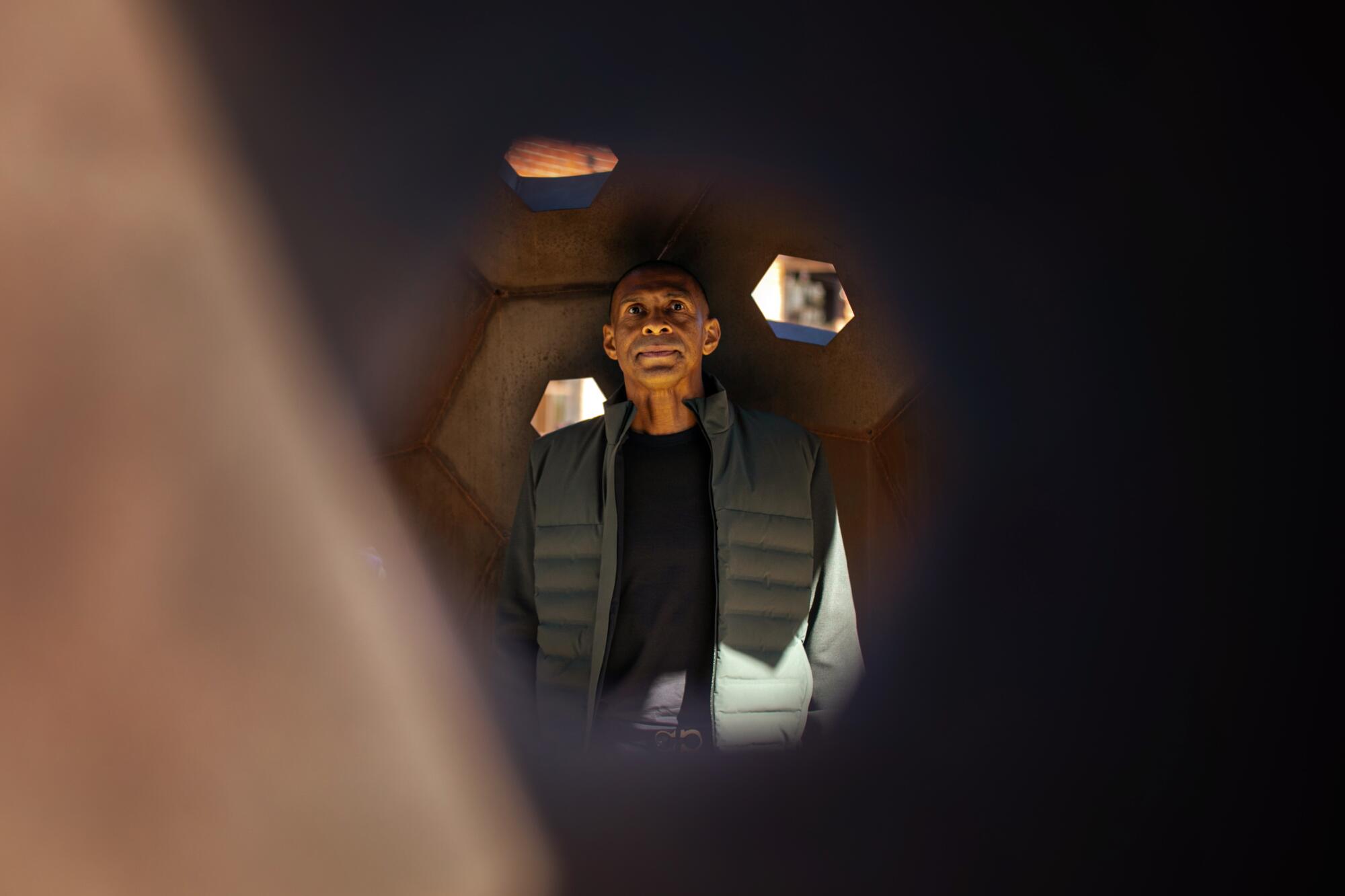

Before it became the Beehive in 2019, the 5-acre campus was three separate parcels of land within the Goodyear tract, an industrial zone in South L.A. known more for auto body shops than day parties. Martin Muoto, founder of the affordable housing and real estate investment company SoLa Impact, had been driving through the area and thought the scarlet brick buildings could be a starting point for his first commercial endeavor.

Muoto grew up in northern Nigeria before migrating to America in 1989 with “$40 and a suitcase” to study at the University of Pennsylvania. After working for national venture capital companies, he moved to Los Angeles and focused on investing in undervalued real estate, much of which happened to be in South Los Angeles.

“Everybody asked where I was investing, and when I said South L.A., Compton and Watts, they said, ‘Oh, you’re going to lose your shirt,’” he recalled. “‘Tenants are going to crash, you’ll be dealing with crime.’ I realized the area was being judged by the old stereotypes from the crack cocaine era. But my central investment thesis was the vast majority of people were good, hardworking people who wanted a safe place for their kids.”

Muoto pursued his venture and eventually founded SoLa Impact in 2015, raising millions in private capital to purchase dilapidated buildings and restore them to rent on the market. But by 2019, he had two ideas to expand the vision. First, he wanted to increase L.A.’s housing supply by building new units, not just renovating existing ones. And second, he wanted to develop SoLa Impact’s first commercial property.

“To really create prosperity, you’ve got to create jobs, you’ve got to create economic development,” Muoto said. “So I said, how do we create an ecosystem that really encourages Black and brown businesses to thrive here? How do we create a central spot where nonprofits can come to really celebrate South L.A.?”

Near the end of 2019, SoLa Impact bought the land through three separate transactions and set to work on a renovation plan. The original idea was to provide space for entrepreneurs, community groups and BIPOC businesses inside the brick buildings — South L.A. Brewery was one of the first to plant a flag, claiming a room where it would create its home base.

But of course, COVID intervened.

“For a long time, I was swallowing very hard,” Muoto said. “Everyone was saying, ‘Businesses aren’t going to come back to work, people aren’t going to use this type of space.’ Everyone was at home. So we ended up investing very heavily in our outdoor space.”

SoLa impact didn’t initially have grand plans for the property’s outdoor areas, but out of necessity they became essential to the Beehive’s survival. The pivot paid off: Companies and community groups came calling, drawn primarily to the warmth of the courtyard.

The lightbulb went off for Muoto when Google came calling and asked to use the space for an event to promote the Google Pixel smartphone’s Real Tone feature, designed to take photos of darker skin tones in a more complimentary light.

“They built a village,” he said. “They built a city. ... They really wanted to make it authentic to the Black community. Them picking the Beehive showed me that even corporations like Google aren’t just talking about diversity, equity, inclusion. They actually want to come roll up their sleeves a little bit.”

Saada Ahmed discovered the Beehive in 2022 when a friend connected her to the then-new venue as a possible site for her traveling party series known as Everyday People. Ahmed had founded the popular event in New York in 2009 and had already planted roots in Los Angeles but took a tour of the space to gauge its potential.

But when she saw the Beehive, she wasn’t just struck by the layout — the fact that it was a Black-owned venue was a breath of fresh air.

“As many venues as we’ve worked with, finding a Black-owned venue is very difficult,” she said. “Even if you go to Africa. And then I took a tour of the space, and they explained to me how they’re working with the students, and even the housing stuff. And I was like, this is in alignment with what I’ve always wanted to do, be a place where we can support Blackness. And it’s beautiful!”

A native of East Atlanta, Ahmed never dreamed of getting into the party business, but she was drawn to the idea of community from a young age.

“One of the things that drew me was not feeling alone,” Ahmed said. “That can come in different forms. I’ve done other stuff like Brothers & Sisters, where we had monthly conversations about stuff we were dealing with. We’ve done Everyday People community sessions, with different forms of healing. I just felt called to make people not feel alone.”

She moved to New York after graduating from Suffolk University but struggled to get a foot in the door at any companies due to a lack of connections. She’d already been throwing parties in the area and, after seeing how popular brunches had become in New York, felt motivated to put her spin on the daytime event.

Ahmed connected with DJ Moma and chef Roblé Ali in 2012, intending to throw a brunch for her community. But the guests had other plans.

“In the beginning, it was a sit-down situation, but you know Black folks,” she said. “They hear a song they like, they’re going to dance. So it kept elevating to a bigger thing.”

Word got around, and with every event Everyday People packed a bigger venue. Before long it outgrew New York, spreading across America and into the Caribbean, Europe and Africa.

Taking Everyday People on the road came with its own set of challenges: Ahmed had to plan an event that felt authentic to its home city, even if it was her first time there. She made a habit of connecting with a new city’s tastemakers to understand the local environment, using Everyday People’s rapidly spreading platform to shine a light through collaboration.

“It’s fascinating, when I was trying to figure out my major in college, I wanted to study anthropology,” she said. “Which had its own implications, because of white people. But I was always interested in culture. So going to different cities to me, it was almost like me doing that study without going to college.”

The Beehive is one of the larger venues Everyday People operates out of, but it routinely sells out each time (even with parties on back-to-back days). Stars from Diddy to Saweetie to Smino have come through but, unlike a typical L.A. club, VIPs aren’t sectioned off in their own, typically less rambunctious area.

“We purposely make everyone mingle,” Ahmed said. “So you’re going to see someone you watched on TV twerking in the middle of the dance floor. It’s literally in the name, Everyday People. You’re going to be weird if you have airs about you.”

“Sometimes you work a corporate job, you’re the only Black person there, or you’re in a city where you don’t see Black people all the time,” she continued. “So it’s nice to be in that environment. We’re Black every day, right? We are dealing with the same struggles. It’s cathartic to dance and release your pain.”

A brick building adjacent to the courtyard houses SoLa Impact’s Technology and Entrepreneurship Center.

There’s a lot going on at the Beehive, but for Chief Impact Officer Sherri Francois, this is the crown jewel. It’s a true 21st century YMCA, filled with virtual reality headsets, entrepreneurship programs and courses that teach kids about the business behind entertainment.

“We’ve only been open and operational just over a year, and fully operational since August,” Francois said. “We know there’s a demand, because we have a waitlist for programming. We could have a tech center on every other block and it still wouldn’t be enough.”

Francois was born in Compton and lived there until age 11, when she moved to the more affluent city of Walnut with her parents. Seeing both sides of the coin at a young age showed her the disparities she and her family had previously dealt with firsthand, despite the two cities being less than an hour apart.

She found her way to a television career producing for CNN, NBC and MTV, thanks to her skills with operating cameras and editing software. But much of her family remained trapped in the generational curses that plague many Black families in Los Angeles.

“For me, it became personal when I came to SoLa,” she said. “We were determined to help break the cycle of poverty, and part of that was getting to the youth early.”

Conversations about the tech center began in 2018, and planning got underway after SoLa Impact purchased the Beehive. In summer of 2020, they launched a pilot program with 20 students, looking to measure demand and prove to investors they could be successful.

Riot Games stepped in to help the cause once there was proof of concept, proving instrumental in building out the programming and sustaining it through the early stages. As the center grew, other companies came in to play a role; Live Nation partnered with SoLa Impact to help aspiring executives break into the music business, and players from the L.A. Rams have come through to interact with the kids.

“The hardest part was convincing folks, because we’re a housing developer first, right? Why are we building a tech center?” Francois recalled. “So convincing folks that we could execute at a level of operational excellence, and have a true impact, took a minute. But now that we have it, and people can touch and see it, it’s tangible.”

The center’s programming is not exclusive to SoLa residents; about 85% of the kids don’t live in the company’s housing. Plans are in motion for a second tech center in the Crenshaw/LAX corridor, in collaboration with City Councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson, who represents the area.

Partnerships have been essential to the center’s survival, Francois emphasized for groups outside of Los Angeles looking to emulate the center. Both she and Muoto are excited about the current and planned center but want to see the model expand across the country.

“If we can do it in South L.A., they can do it in Watts,” Muoto said. “If they can do it in Watts, they can do it in Philadelphia, or in Tulsa. We want to be an open book here. If you want to come beg, borrow and steal our best ideas and then do it in Tulsa, come on down.”

The success stories are evident. A student named Jailah Walker sells sneaker candles after creating the concept in the entrepreneurial program, and has already sold her items at a pop-up outside the tech center (and through her Instagram storefront). Parents routinely tell Francois and Muoto how excited their kids are to come to the campus each day. “We’ve heard parents say, ‘I can’t get my kids to get up and get dressed for school, but during the summer, they’re up at 7:30 like, ‘Mom, are we going to the tech center?’” Muoto said.

About 125 graduates from the program have received scholarships to college, their likenesses memorialized on a scholar wall that shows all their faces. Francois remembers a current student named Langston staring up at the various headshots, envisioning his future photo plastered up high for all to see.

“Thank you for this space,” Francois recalled Langston telling him. Then, he pointed to the scholar wall: “And just so you know, someday I’m going to be on that wall.”

He pointed to the donor wall next. “And then someday, I’m going to be on that wall.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.