A striking Danish art show at the Getty unpacks what it means to be a nation in turmoil

- Share via

Almost five years ago, the J. Paul Getty Museum acquired a very beautiful, very strange painting by a 19th century Danish artist not widely known outside Northern Europe. The museum’s recently opened exhibition “Beyond the Light: Identity and Place in 19th Century Danish Art” provides a surprising — and surprisingly relevant — backstory for the unusual acquisition.

Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864-1916) is revered in Copenhagen, where he was born and lived throughout his career. Periodic bursts of attention arrive in the United States with exhibitions that include his paintings and drawings. Two dozen works were borrowed from the National Gallery of Denmark for a 2015 solo show at New York’s Scandinavia House, and he appeared in the big, landmark 1982 group survey at the Brooklyn Museum, ‘’Northern Light: Realism and Symbolism in Scandinavian Painting 1870-1910.”

The Getty’s “Interior With an Easel, Bredgade 25” depicts the home the artist shared with his wife, Ida, for the last three years of his life. (He was 48 when he painted it.) The canvas, 31 inches high and just under 28 inches wide, is a view into rooms mostly empty, except for the shadow-inflected play of soft gray light drifting in from unseen windows just beyond the frame.

It’s a superlative example of a subject Hammershøi painted often, beginning in 1898. If you’ve seen “The Danish Girl,” the Tom Hooper movie about early 20th century trans artist Lili Elbe, you’ll have some idea of the painting’s almost abstract geometric design and ethereal mood. The apartment in which the two main characters reside was based on Hammershøi room paintings, and the production design (by Eve Stewart and Michael Standish) received one of the film’s four Oscar nominations.

The painting is a frontal view into a large domestic room with high ceilings. The canvas is bisected vertically by the edge of a door that is opened onto another room behind it, then divided again on the horizontal by receding layers of space. Diffused light pours in on a diagonal, cascading from the left down the gray back walls of both rooms and reflected on the expanse of gray floor in the foreground.

The floor reflection angles up to the right, as if to bounce light back into an enclosed, atmospheric space. The entire picture is a dazzling construction of complex linear geometry, some physical from the apartment’s architecture and some optical. Together, they conspire to create a space of emphatic interiority.

That’s not what’s strange. The tantalizingly weird element is the pair of paintings depicted within the larger painting.

One stands on an easel. A dark-gray rectangle has its back to us, denying our prying eyes. Its dimensions roughly repeat the ratio in the Hammershøi.

The other is in a gilded frame and hangs behind the easel — not just on the wall but skied, way up at the edge of the ceiling, like a helium balloon floating away. The hanging is totally irrational, as if intended to throw the otherwise coherent logic of the entire composition out of whack.

It works. The painting up there at the ceiling’s edge is a down-to-earth landscape, rendered in muted colors. Together with its blank companion on the easel, the two paintings-within-a-painting of luminous empty rooms give us unknowable places where imagination drifts.

Commentary: LACMA has transitioned to a de facto contemporary art museum. But not a very good one

LACMA might be a de facto museum of contemporary art, but frankly it’s not a very good one.

The poetic, light-filled merger of such realist and symbolist tendencies was not uncommon in European and American art of the period. The picture dates to 1912, which is a dozen years beyond the Getty’s usual cutoff date for acquisitions in its European paintings collection. But its dreamlike sensibility began taking shape in Danish art decades earlier, which the exhibition beautifully articulates — mostly through works on paper.

The show was deftly organized by Getty drawings curator Stephanie Schrader, Yale University Art Gallery drawings curator Freyda Spira and Thomas Lederballe, chief curator at the National Gallery of Denmark. In addition to a dozen paintings, it features more than 60 drawings, prints and oil sketches on paper by nine artists, including Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, Christen Købke, Constantin Hansen and Martinus Rørbye.

More than a generation has passed since this art was the subject of a major U.S. exhibition. The Brooklyn Museum’s “Northern Light” set the terms: The luminosity is what counted. Light and spatial abstraction spoke to contemporary interests in perception, represented by artists as diverse as Mark Rothko and Robert Irwin.

“Beyond the Light,” as the Getty show is pointedly titled, looks elsewhere. Social history is its driver.

The aim is to reconcile a stark contradiction. The work’s serene precision and contemplative subjectivity emerged during a period of epochal upheaval in Denmark. Economic chaos in the brutal wake of Napoleonic Wars was shoved into bankruptcy by British intervention. The absolute monarchy collapsed. Building democracy from scratch was a struggle. The exhibition productively frames this art as a visual exploration of what it means to be a nation in abject turmoil.

These days, Americans can relate.

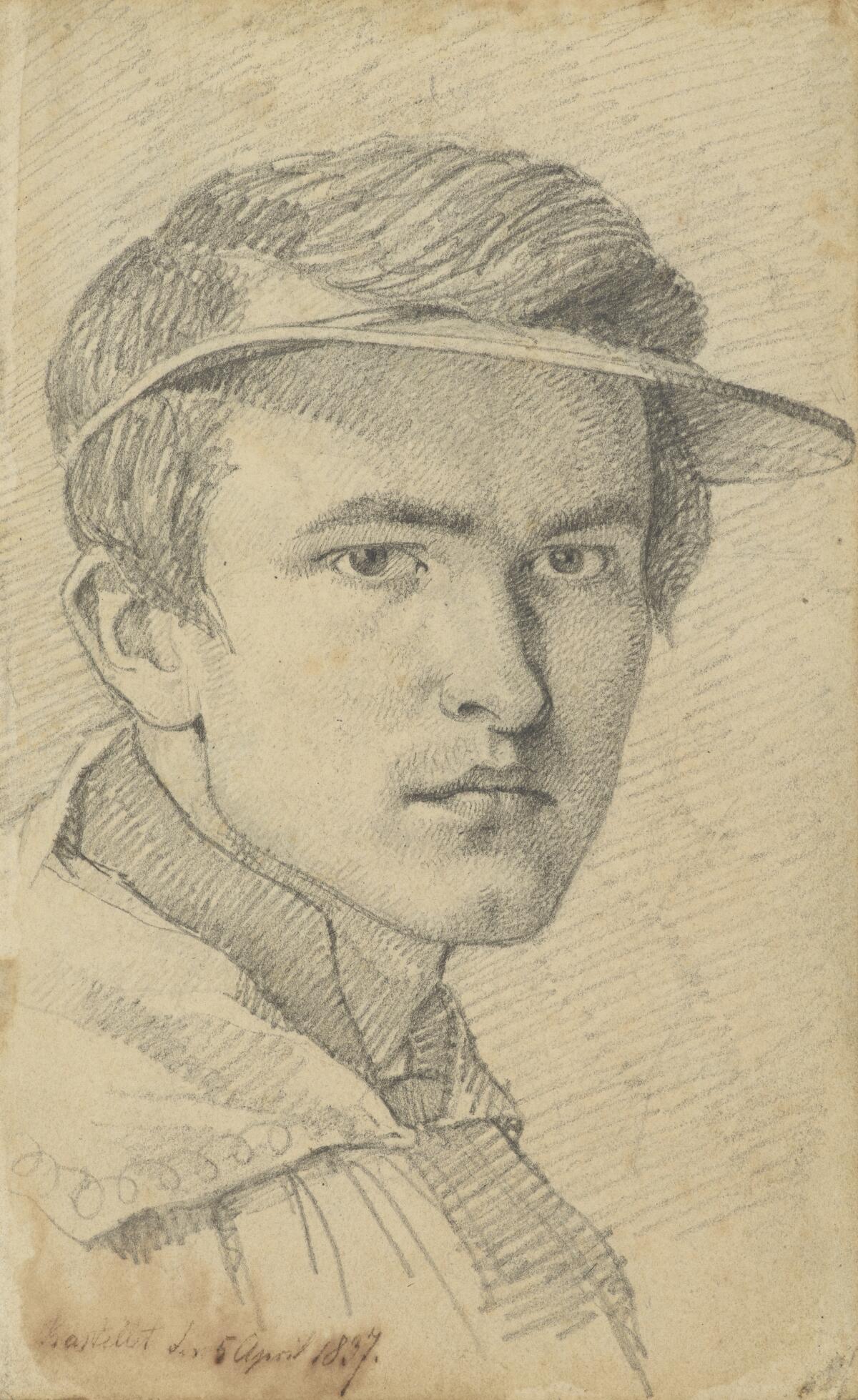

Not that you might know the social trauma from casual perusal of most of this work. The starkest hint comes in a melodramatic drawing of a despairing young man, head in hands, by Johan Thomas Lundbye. More subtly, in a remarkable ink portrait of painter P.C. Skovgaard, Lorenz Frølich poses the sitter’s torso in three-quarter view, arms folded and his head in sharp profile. It’s as if he’s quietly turning away from our scrutiny, unwilling to engage. Calm overrides the storm.

The show is divided into three primary sections, with an addendum that assembles pictures made as artists traveled around the Mediterranean to Turkey, Greece and especially Italy. “Seascapes and Landscapes” considers everything from Denmark’s seafaring identity to its spiritual history, with megalithic tombs speaking of time’s eternal, melancholic passage. “Monuments of a Danish Nation” represents transitory people, places and things that tie people together in common traditions and beliefs. “Founders of a National School” looks at the establishment of an idealized shared aesthetic in an effort to represent, or maybe create a unified culture.

Sometimes change appears as a subtle adjustment in viewpoint. Købke, perhaps the most astute of these artists, gave a detailed view of the now-dormant Mt. Vesuvius at Pompeii that is less a landscape masquerading as a classical history painting than an elegiac meditation on wholesale ruin. The foreground is shadowed, spotted with flowering weeds, while goats cavort among wrecked buildings and fallen columns in the luminous middle ground, where aristocrats once played.

Sixteen Købke works are included. His tragic death from pneumonia at just 37 robbed us of a major artist.

Heinrich Gustav Ferdinand Holm drew an acutely precise, preternaturally quiet, almost heavenly aerial view of Copenhagen from the tower of a royal palace. Yet his exquisite graphite drawing positions a viewer behind an iron railing decorated with the elegant tracery of the king’s monogram. The railing forms a perceptual veil through which we take in the urban scene, indicating a sight once reserved exclusively for royalty but now available to citizenry. Who’s omnipotent now?

In ink and watercolor, Lundbye portrays an artist drawing the coastal landscape outdoors, as he leans back against a funerary dolmen with sketchpad in hand. With mortality as support and a gray cloud lowering in the sky, the task of creation is set within a vast topography where land meets sea.

The Købke, Holm and Ludbye works were all made within five years of one another, some 60 years before Hammershøi’s strange and beautiful domestic interior. Prominent handling of natural light animates all of them. Now, however, it begins to signal thoughtful awareness of life’s complexities — social, political and cultural.

'Beyond the Light: Identity and Place in 19th Century Danish Art'

Where: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Brentwood

When: 10 .a.m–5:30 p.m.,Tuesday-Friday and Sunday; 10 a.m.-8 p.m. Saturday. Through Aug. 20.

Info: (310) 440-7300, getty.edu

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.