- Share via

Berkeley and New York — When theorists Amalia Mesa-Bains and bell hooks got together to write a book in 2017, they didn’t produce a collection of essays or some scholarly manifesto. Instead, the pair sat down and had a series of conversations. The book that emerged, “Homegrown: Engaged Cultural Criticism,” is marvelous for its thoughtfulness and its accessibility, exploring the roots of culture, how it is generated but also how it can be suppressed and erased.

Mesa-Bains, a mestiza Chicana from the Bay Area, and hooks, a Black woman from Kentucky, devote a chapter to memory. “Memory allows us to resist and to heal,” says hooks. She goes on to refer to a well-known quote by Spanish filmmaker Luis Buñuel: “You have to begin to lose your memory, if only in bits and pieces, to realize that memory is what makes our lives. Life without memory is no life at all.”

Memory is at the heart of a pair of captivating and long-overdue exhibitions currently on view on opposite coasts.

At the Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive, Mesa-Bains — an artist as well as an important scholar — is the subject of a career retrospective — her first. The show reunites nearly 60 works, including many of her sprawling altar-style installations inspired by themes of family, spiritual rite, the feminine body and politics.

Across the continent in New York City, the Whitney Museum of American Art also has an important retrospective on view: nearly five decades of work by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, a citizen of the Confederate Salish and Kootenai Nation, whose bold paintings borrow the iconographic language of Pop to assert the Native presence in the United States. Both exhibitions are on view through mid-August.

Both shows incorporate the word “memory” in the title. Mesa-Bains’ retrospective is subtitled “Archaeology of Memory,” while Smith’s bears the designation “Memory Map.” Through their work, both artists have introduced important narratives about the Chicano and Indigenous experience, respectively, in institutions where these have long remained out of view. “Our collective memory,” Mesa-Bains says in “Homegrown,” “has been suppressed by educational institutions and the mass media.”

Together, these exhibitions work to remedy that. And they have more in common besides, marking analogous personal and cultural histories.

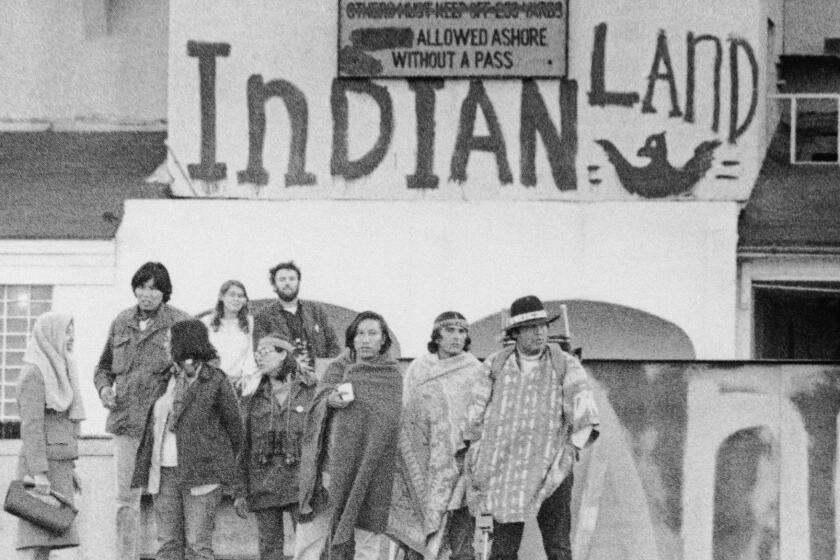

Column: Indigenous tribes took over Alcatraz 51 years ago. Read the ‘holy grail’ of the occupation

A logbook digitized by the Autry Museum reveals tribal activists and celebrities who came to Alcatraz during a 19-month occupation that began in 1969.

Both women were born in the same decade: Smith in 1940, on the Flathead Reservation in Montana, and Mesa-Bains in 1943, in the Santa Clara Valley (a.k.a. Silicon Valley), to Mexican parents without documents. Both artists have been influential activists, educators and curators: Mesa-Bains’ theories around Chicana domestic spaces inspired the group show “Domesticanx” at New York’s El Museo del Barrio last year; this fall, Smith is organizing a group show of 50 living Native artists, “The Land Carries Our Ancestors,” for the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

Both artists have talked about feeling disillusioned with and excluded by the second wave feminist movement of the 1970s. And both have created works inspired by mapping, questioning how the borders of the United States have overwritten what was here before. Both have also tackled, in distinct ways, myriad issues around Indigeneity — countering, for instance, the celebratory approach taken by many institutions toward the 1992 quincentennial of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the Americas.

Two years before that anniversary, Mesa-Bains presented a room-size installation at Phoenix’s M.A.R.S. Artspace (now the Phoenix Institute of Contemporary Art) that challenged romantic ideas about the settlement of the Americas. It contained a cabinet — evocative of Victorian-era curiosity cabinets — that featured arrangements of pre-Columbian-style figurines and shards of pottery alongside disconcerting medical instruments and tools of restraint. Placed next to the cabinet was a Louis XIV-style armchair that the artist had bathed in gold paint and then stabbed repeatedly, stuffing its wounds with her own hair and that of fellow Chicanas.

The cabinet is not part of the Berkeley retrospective, but “The Autopsy Chair” is included. And it is a disquieting work: a golden throne, the seat of conquest, upholstered with bits of literal bodies.

The quincentennial likewise fueled critical works by Smith, such as her ongoing “I See Red” series, which embeds a pejorative term used to describe Indigenous people within a figure of speech about rage. The works reference various aspects of Native life: a can of mutton stew or Petroglyph National Monument outside Albuquerque (a protected cultural site that the artist helped establish).

In keeping with the name, a number of the paintings in the series are bathed in layers of viscous red paint, such as “I See Red: Snowman,” painted in 1992, which shows the outline of a snowman (an interesting stand-in for whiteness) hovering over a mostly red background collaged with pieces of U.S. flags and snippets of print ads for ’92 Jeep Cherokees. Also included are pages from the Flathead Reservation newspaper: One advertises a local art exhibition; another notes the layoff of 331 workers by the Winnebago Tribe.

In its bloody tones and its message, it is a work that scorches — a masterful indictment of the ways Indigenous people have been reduced to mascot and brand name while day-to-day concerns remain out of view. As Smith told historian Lowery Stokes Sims, in an interview for the exhibition’s excellent catalog, the series is meant “to remind viewers that Native Americans are still alive.”

If there are overlaps in Smith’s and Mesa-Bains’ work, there are marked aesthetic differences too.

Smith studied art and arts education, first in Washington state (where she spent a good deal of her youth), then in Framingham, Mass., before ultimately receiving her master’s in visual arts from the University of New Mexico in 1980. A trip to New York City in the 1970s exposed her to the work of Fritz Scholder, an enrolled member of the La Jolla Band of Luiseño Indians, whose wry, Pop-inflected canvases skewered Native tropes. In one of his best known paintings from 1971, “Super Indian No. 2,” a man in a buffalo headdress enjoys a pink ice cream cone.

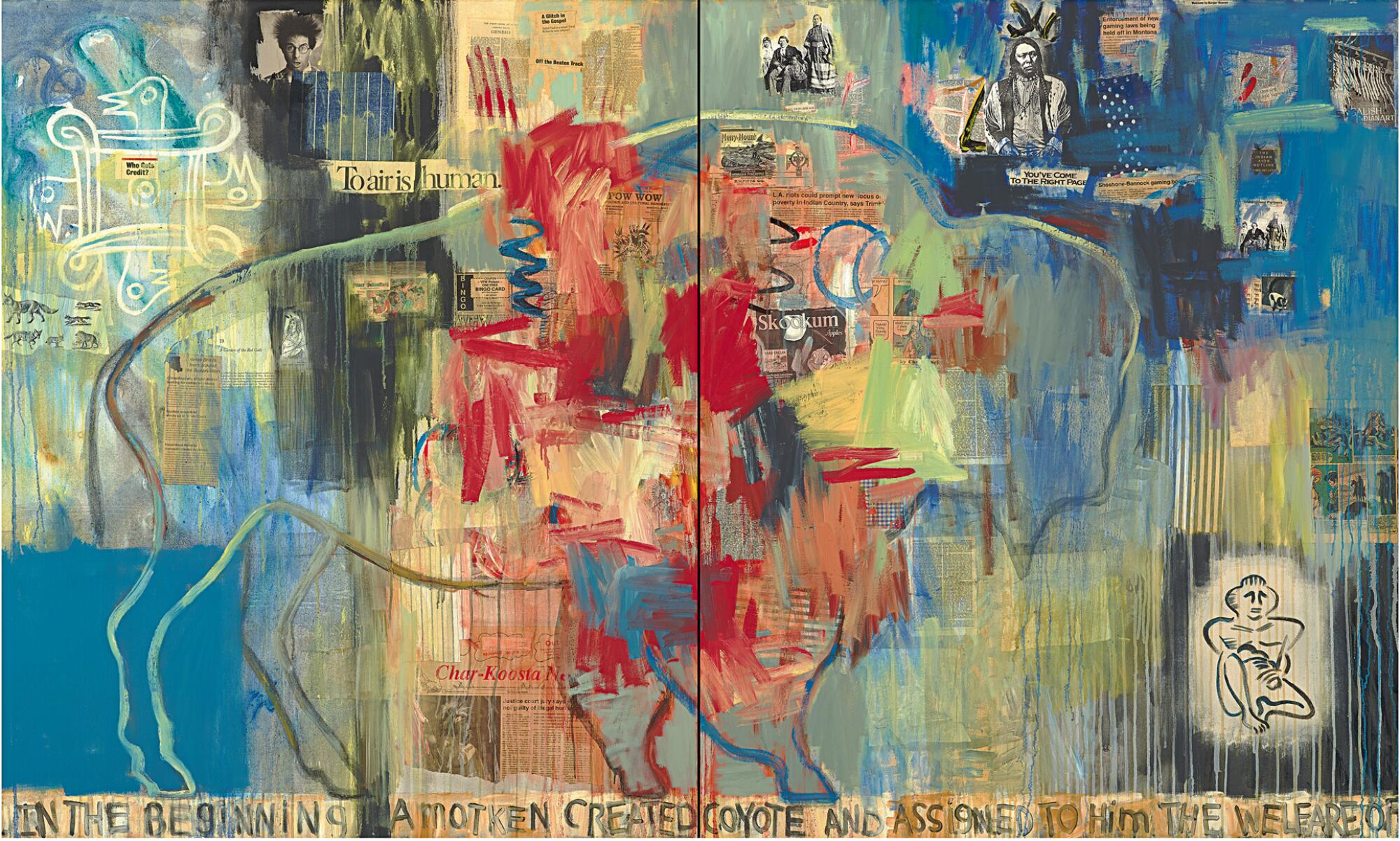

Smith says she was “dazzled” by Scholder’s work. Other influences also materialize, including the multimedia works of proto-Pop painters such as Robert Rauschenberg, who integrated news clippings and other objects onto his canvas, and Jasper Johns, whose textured canvases of flags, targets and maps rendered quotidian objects enigmatic.

The Vincent Price Art Museum is showing work by 30 sonic artists, from punk band Nervous Gender to experimental composers Raven Chacon and Guillermo Galindo

Smith’s Whitney retrospective — the museum’s first for an Indigenous artist — brings together more than 130 works over two floors. The show is an absorbing chronicle of the artist’s leaps as a painter, moving from lean abstracted landscapes in the 1970s into the larger-scale, more expressive, collaged canvases for which she is now known. Buffaloes, horses and flags materialize as prominent symbols in canvases whose carefully constructed backgrounds continuously articulate the Native presence and question the idea of who and what is considered “American.”

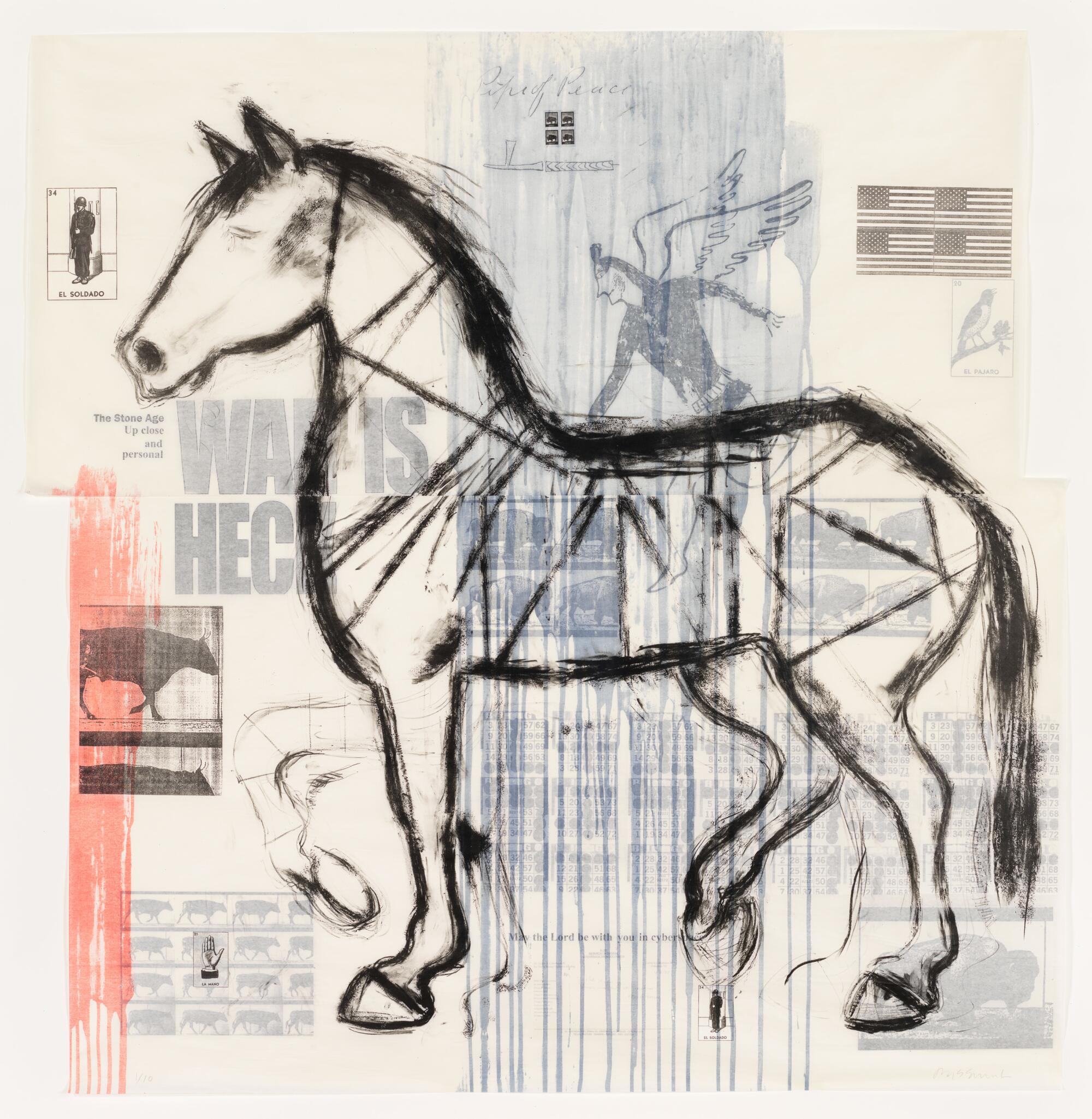

Her critiques of the imperial project extend well beyond the borders of the United States. Particularly powerful are a series of works from the mid-aughts critical of the Iraq war, such as “Trade Canoe for Don Quixote,” from 2004, and “War Horse in Babylon,” completed the following year, with their chaotic arrays of skulls and shrieking figures reminiscent of “Guernica.” Like Picasso’s original canvas, these are a cry against senseless war.

Where Smith draws from Pop to make a statement about the Native condition, Mesa-Bains imports the rituals of her hybrid heritage (she also has some Black ancestry) into a gallery context.

Her practice of creating altars and ofrendas (offerings) draws directly from the traditions of her family, such as the home altar kept by her grandmother, cluttered with Virgins and saints and even an image of John F. Kennedy. The home altar also has roots in Indigenous spiritual practices, and it is frequently maintained by women, making it a vital feminine space that, as Mesa-Bains notes in “Homegrown,” serves as “a counterpoint to church patriarchy.”

Her earliest altars, in fact, were to women. A 1976 installation, displayed at San Francisco’s Galería de la Raza for Day of the Dead, honored women, including family members, close friends, fellow artists and Mexican painter Frida Kahlo. It’s a gesture that, over time, has spawned ever more elaborate, complex and conceptual installations that nonetheless remain intensely personal.

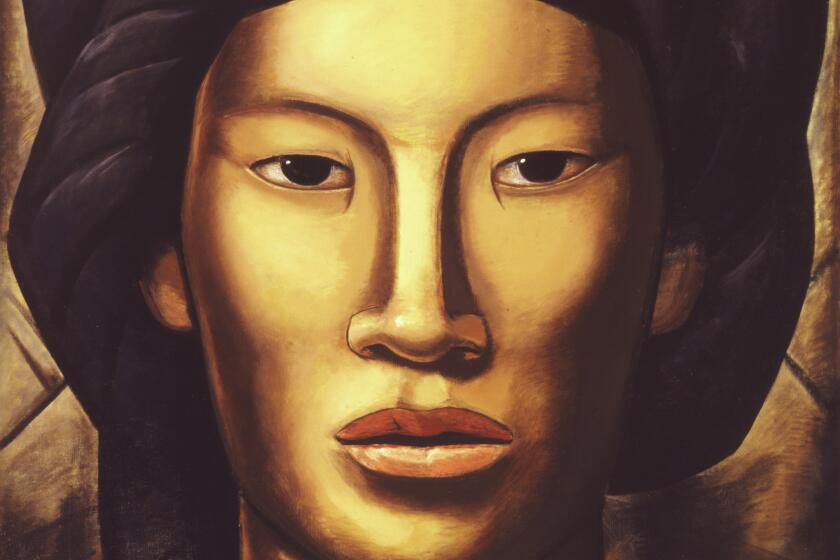

‘Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche’ at the Denver Art Museum reconsiders a foundational figure in Mexican national mythology.

At the Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive, a wooden desk, for example, becomes the site of an altar to 17th century Mexican poet Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (who wrote one of the great takedowns of male hypocrisy in a Spanish redondilla titled “Foolish Men”); an armoire draped in flowers and moss becomes a way of commemorating her family’s relationship to the land over a century and a half.

Tucked into these meticulously arranged installations are a staggering number of details: ceramics, framed poems, photographs of historic figures, lotería cards, maps of the cosmos, sage bundles and even a skull.

One of the most enthralling, however, is a sprawling early piece titled “Venus Envy Chapter I: First Holy Communion, Moments Before the End,” which emerged from an extraordinarily challenging period in the artist’s life.

In the early 1990s, Mesa-Bains fell ill with cardiopulmonary disease, and her doctors feared she had only a few years to live. In an interview published in the catalog (which, like Smith’s, was conducted by Sims), Mesa-Bains describes the diagnosis as her “come to Guadalupe” moment. Until that time, her altars had been ephemeral projects, assembled and disassembled, with objects frequently reused.

But, facing mortality, she began to conceive of them as discrete works of art. Thus began a series, “Venus Envy,” in which individual installations were “chapters,” visual manifestations of the artist’s autobiography. “Venus Envy Chapter I” was inspired by Mesa-Bains’ Communion, a Catholic rite that marks a transition to womanhood and represents a unique moment of engagement with other women: finding a dress, choosing a veil, receiving family keepsakes from elders.

‘Migrant Dubs’ was created by Los Jaichackers and shown in the groundbreaking ‘Phantom Sightings’ in 2008. Now it’s a sound studio for DJ Escuby

This room-size installation explores female archetypes of the bride, the nun and the virgin. One component centers on a vanity dresser — the site where a woman prepares to present herself to the world — which Mesa-Bains has covered in a dazzling array of objects: statuettes of virgins and saints, flower petals, seashells, framed family photos and hundreds of shimmering craft pearls. Elsewhere, vitrines gather the objects of her life, including keepsake rosaries, prayer cards, many more vintage photographs and a pair of braids tied neatly in white ribbon.

Like all her installations, it delivers surprises. Stare into the vanity’s mirror and it won’t be your own face that confronts you; Mesa-Bains has scraped off the mirror’s backing and inserted an image of Coatlicue, a Nahua female deity that is both creator and destroyer. It’s a reminder that Catholic ritual in Latin America is often a syncretic interpretation of existing Indigenous rite.

Together, the works of Mesa-Bains and Smith serve as a vital counter-record to dominant narratives about Indigenous people and Mexicans. But it’s the objects of everyday life woven into the pieces that make the works so personal and so powerful — a way of archiving stories and objects that might otherwise be discarded.

Smith’s paintings are studded with powwow fliers and clips from reservation newspapers; she also frequently writes place names into her canvases. “Almost everything you see in my drawings has the name of a place on my reservation,” she states in the catalog, “because I’ve been mapping the reservation.”

Mesa-Bains, meanwhile, has used her art to create a rich archive of Chicano life that goes far beyond what you’ll ever find in mass media. In an altar, she tells hooks in “Homegrown,” “You will see the medals from your uncle who died in the war, you will see your own baby booties, you will see the dried flowers from your cousin’s wedding, you will see the images of your mother and father as a young bride and groom, you will see the face of your great-grandfather, and you will see the image of the newborn child, because they are all in a cosmology of the family centered in memory that is linked to the present.”

Everything the history books didn’t — or wouldn’t — tell you.

'Amalia Mesa-Bains: Archaeology of Memory"

Where: Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive, 2155 Center St., Berkeley

When: Through Aug. 13

Info: bampfa.org

'Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map'

Where: Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort St., New York

When: Through Aug. 13

Info: whitney.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.