- Share via

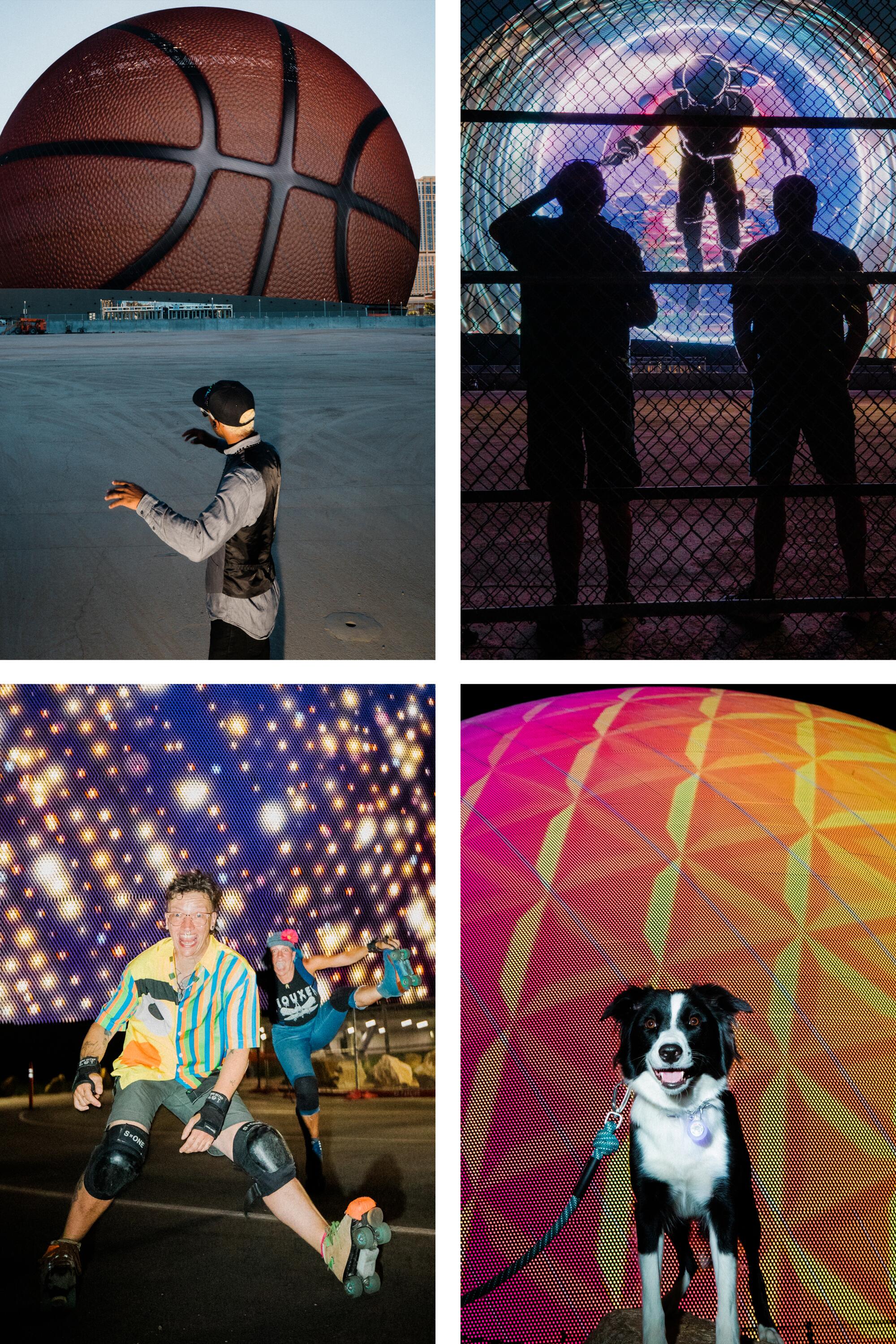

LAS VEGAS — It’s 9 p.m. on the Strip and 100 degrees out and I’m staring at a blue ball. It pulses and turns. It becomes purple. Then pink.

No ordinary ball, this throbbing, churning globular body, formally known as Sphere (no “the”), is Las Vegas’ newest performance venue. Sphere doesn’t open until later this month, but it has already gone viral for the assortment of otherworldly images that have materialized on its surface since July Fourth, when Sphere Entertainment Co., the entity that built and manages it, turned on the lights. Since then, the building’s LED skin — the highest-resolution LED screen on Earth, according to Sphere public relations — has displayed artificial intelligence-generated art by Refik Anadol, images of the cosmos, a grinning jack-o’-lantern and, most disconcertingly, a ginormous blinking eyeball.

Sphere is an internet sensation. A Sphere Fan Club on Facebook grew from 55,000 to more than 82,000 members in the few short weeks I was reporting this story. Sphere is also a darling on TikTok, where you can not only view a mind-boggling number of Sphere videos but also use a filter to make it appear as if Sphere were projecting your head. In a town (Vegas) and an industry (entertainment) where superlatives get tossed around like sand in the waves, Sphere commands them all.

Yet Sphere is not a meme; it is a real structure in a real city — although arguably the most unreal city, of which Sphere feels both like a natural evolution and a supernatural deviation. Any familiar object blown up to a height of 366 feet can feel unsettling, but the looming orb has had the effect of turning the glitzy Vegas cityscape, including the pricey Wynn Golf Club across the street, into a painting by Salvador Dalí: namely, that 1945 canvas showing a disembodied eye hovering over a desert.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

I traveled to Las Vegas late last month to behold Sphere, seeking an experience akin to the scene in Philip K. Dick‘s 1957 novel “Eye in the Sky” when the protagonist is catapulted into the heavens and gazes, briefly, into the eye of God.

Instead of God, however, I got U2.

On the night I visited, Sphere was merely a pink-purple-blue ball bearing the logo “U2:UV,” an advertisement for the series of U2 concerts that will inaugurate the venue. U2 greeted me from the footbridge that connects the Venetian and the Wynn. U2 beamed into my capsule in the High Roller Ferris wheel. U2 was still there, in the middle distance, when I landed in my hotel room at the Flamingo. It felt like 2014, when iTunes users the world over woke up to discover that a U2 album had been delivered to their playlist whether they wanted it or not.

Refik Anadol’s AI data sculpture, “Machine Hallucinations: Sphere,” will debut Sept. 1 on the exterior of the futuristic Sphere venue in Las Vegas.

The ad was a graphically disappointing turn from a band whose 1997 PopMart tour was pure Vegas excess. And it was doubly disappointing because it supplanted one of Sphere’s beloved nightly features: between 10 and 11 p.m., the building usually displays an image of a gently rotating moon. The night I happened to be in Las Vegas was the eve of the recent super blue moon, meaning that I could have seen two brilliant moons at once — like a scene out of Frank Herbert’s “Dune” or Haruki Murakami’s “1Q84.” But, no. I was witnessing U2.

Sphere is part of a long Vegas tradition of buildings swathed in billboards.

As I entered Hour 3 of watching the largely unchanging ad from various vantage points, I gave up on having an encounter with the surreal and came to terms with the fact that I’d flown to Vegas to look at a billboard. Though, in truth, looking at a billboard is the ultimate Vegas experience.

…

Sphere is not the tallest structure in the city. (That’s the Stratosphere, a.k.a. the Strat, which checks in at 1,149 feet — more than three times Sphere’s height.) It is also not the first musical venue located inside a sphere. The Kugelauditorium, a spherical concert hall devised by electronic composer Karlheinz Stockhausen and built by architect Fritz Bornemann for Expo ’70 in Osaka, Japan, served as precedent. This summer, a second-generation version of that project was presented by the Shed art space in New York City.

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

It is also worth noting that Sphere is not on the Las Vegas Strip. It resides one long block to the east, at a traffic-jammed intersection marking the walled borders of the Wynn Golf Club, an anodyne office park and an unsympathetic tangle of casino parking structures. Walking nearby is absolutely demoralizing. Sphere, moreover, is not even visible from much of the Strip itself; the views are largely blocked by hotel towers.

The building is, however, visible from upper stories of those towers. It can also be seen from just about everywhere else: from an airplane as you land at Harry Reid International Airport; from I-215 as it bends north from Henderson; from the Las Vegas Monorail as it turns onto Sands Avenue; from the drive-through of the McDonald’s on Paradise Road. Pull into the parking lot of the Vons supermarket at Tropicana Avenue and Maryland Parkway and you can see Sphere looming just behind the School of Architecture at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

The joy of Sphere, to some degree, is rounding a corner and confronting its behemoth, blob-like form unexpectedly.

Chris Brehaut, a Las Vegas engineer who serves as a moderator of the Facebook fan club, has an unobstructed view of Sphere from his living room in an apartment tower north of the Wynn — a location that offers the sublime juxtaposition of the eyeball and the tidy greens of the golf course. Though initially concerned by how much light Sphere might project into his living room, he says he now looks forward to the nightly spectacle.

“It’s not an overpriced restaurant, it’s not a bar, it’s not a nightclub,” he says. “Instead, it’s like the treasure hunt of finding the best view of the Sphere.”

The interiors of Sphere, for now, remain under wraps. The architects — Kansas City, Mo.-based firm Populous — declined to talk about the design. And when I asked for a walk-through from Sphere public relations, I was told something something testing would make a visit impossible. It is possible, however, to glimpse the colossal, unfinished interiors in a somewhat uncomfortable promotional video created by Apple Music in anticipation of U2’s shows. You can also find both leaked and official video of graphics tests on social media.

What can be confirmed about this $2.3-billion arena is that it will seat almost 18,000 people and will feature a surround-sound experience as well as a haptic system allowing some attendees to “feel” the sound in their seats. Immersive video on curving LED screens within the venue will also be part of the equation. Guy Barnett, a senior vice president at Sphere Entertainment Co., tells me that the experience will be like “a theater in the round.”

What we also know, from a report in the Las Vegas Review-Journal, is that some of the seating decks block views of the screens. This may not be an issue for live shows, since views of the stage reportedly remain unobstructed. But it’s unclear how it will affect other presentations, such as “Postcard From Earth,” a film that was made for the space by director Darren Aronofksy that is scheduled to premiere in October.

At this point, however, I’m less interested in the guts of the building than in how what Barnett calls “the only spherical LED billboard in the world” connects to Las Vegas.

…

Sphere may be new, its shape unusual, but it emerges from a long and storied architectural legacy. And I’m not talking about the spherical cenotaph that 18th century French architect and theorist Etienne-Louis Boullée proposed in honor of Isaac Newton.

The Las Vegas Strip — the 4-mile stretch of Las Vegas Boulevard between Sahara Avenue and Russell Road — is a place whose aesthetics have been molded over the decades by gangsters, corporate titans, the worst tendencies of car culture and a general lack of regulation. (The Strip, unlike Fremont Street, the older casino district downtown, does not actually lie within Las Vegas city limits; it is in unincorporated Paradise, Nev.)

This article was originally on a blog post platform and may be missing photos, graphics or links.

In the 1950s and ’60s, the mob brought flash, covering structures with illuminated signs of improbable scale to catch the eyes of passing motorists. In the 1970s, when the corporations moved in, CEOs simply pumped up the volume. They built bigger and taller and shinier and turned the Strip into a series of theme parks, beginning in 1989 with the Mirage, which featured an erupting 54-foot volcano. The following decade, they began creating simulacra of other cities, such as New York, Paris and Venice. By the new millennium, starchitects were being invited to build on the Strip (not very successfully).

This colorful history is chronicled in Stefan Al’s engaging 2022 book, “The Strip: Las Vegas and the Architecture of the American Dream,” which turned me on to an important Sphere forebear: a ’60s-era seafood restaurant at the Dunes hotel called Dome of the Sea. Built in the shape of a saucer-like dome, it featured a woman playing a harp on a seashell at the center of the room and projections of fish and seaweed against the sloping walls — projections so lifelike that they reportedly made some patrons seasick. (Here’s hoping Sphere comes with barf bags.)

Michael Green, co-author of “Las Vegas: A Centennial History” and chair of the history department at UNLV, sees Mirage-era spectacle embedded in Sphere. “The Sphere is a continuation of the volcano, the fountains, the canals, the pirate show — it fits in with that,” he says. “What’s different is that I’ve never before had the feeling that one of the Strip attractions was watching me.”

Op-Ed: Deep down, Las Vegas isn’t ‘alien territory.’ It just plays that way in our imaginations

LAS VEGAS — On a hot and cloudless Sunday afternoon early last month, I took an architecture tour of the Las Vegas Strip.

Where Sphere may signify something new, however, is in combining its extravagant shape with its extravagant billboard-ness.

Traditionally, to admire buildings on the Strip is to admire the billboards that encase them, since the buildings themselves are invariably dull, especially in daylight. In 1972, a group of scholars from Yale University — Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour — published a wildly influential study of the Strip’s “architecture of persuasion” titled “Learning From Las Vegas.”

Their book breaks buildings out into general categories based on how they communicate their purpose to passersby. Buildings that take on an unusual shape to advertise a function — like a duck-shaped building that sells duck merchandise — they baptized “ducks.” A plain, boxy structure with signage on its surface or on a separate pole became a “decorated shed.” “Learning From Las Vegas” notes the critical importance of signage to the Strip, where visitors overwhelmingly arrive by car. “The graphic sign in space,” they write, “has become the architecture of this landscape.”

So is Sphere, with its unusual shape, a duck? Or does its billboard surface make it a decorated shed? Joshua Vermillion, an associate professor of architecture at UNLV who specializes in computation and digital design, says it’s both: “It’s the hero of duck. And yet it’s probably the most extremely decorated shed in the entire universe.” Large billboards with sophisticated motion graphics are a standard part of the landscape on the Strip, he notes, but “to cover the entire thing with a video screen is pretty audacious.”

Ultimately, this sheddiest of sheds and duckiest of ducks marks how Strip architecture has evolved to meet the age of TikTok. Many of Sphere’s biggest cheerleaders have yet to see it in person. Vinton Hulcome, known as “VinDon,” the founder of the Facebook fan club, is a musician from Jamaica who has never seen Sphere in real life, but was intrigued by it the moment he saw early construction photos online. “I’m like, yo, when this is finished,” he tells me by telephone from Manchester, a parish west of Kingston, “this is going to be a monument.”

…

Sphere, interestingly, could end up being specific to Las Vegas in ways that previous architecture has not. The Strip is stuffed full of ideas that have been carted in from other places: ancient Egypt, medieval Europe, the tropics. When the Raiders relocated to Las Vegas, they pretty much took the design for their Carson stadium with them.

“This feels like our own,” says Vermillion. “It’s not something we stole from Oakland, it’s not New York or the Roman Colosseum.” (Although that may not be the case for long. The company wants to build another sphere in London, where the concept has not been as warmly received; “monstrosity” is one adjective that has been hurled at it.)

My latest big story is here. Plus, all the news from around the West.

In fact, there is one influential Las Vegas aesthetic that Sphere embodies above all: the immersive environment.

Decades before experiences such as Rain Room and “Immersive Van Gogh” were even vague notions in their creators’ imaginations, Las Vegas had already pushed the concept of immersion to its limit. At Circus Circus (completed in 1968), trapeze artists practiced acrobatics over a gambling floor tucked inside a plexiglass circus tent. That same decade, you could book a table at the Roman orgy-themed Bacchanal restaurant at Caesars Palace, where servers called “goddesses” would hand-feed you grapes. As Hunter S. Thompson wrote in “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas,” published in 1971, “this is not a good town for psychedelic drugs. Reality itself is too twisted.”

Sphere promises similarly immersive experiences, albeit with digital screens instead of servile women in togas.

How long will Sphere hold our imagination? That’s impossible to tell. “Will this outlive other things?” asks Matt Victory, a Las Vegas musician I met on the Strip. “Or will they tear it down in five years?” Neither outcome, it seems, would surprise him.

One of the important lessons of Vegas is that a clever immersive environment can be crafted out of anything — certainly, for way less than $2 billion. On my way to the airport out of the city, I made an 8-mile detour to Henderson to visit Cantina Tequila, a new Mexican restaurant I’d learned about on TikTok that not only features a dazzling Walter Mercado mural in the dining room but also a women’s restroom that doubles as a shrine to Pedro Pascal. Collages of the actor on the walls and stalls are accompanied by flashing lights and a musical medley that includes Right Said Fred‘s “I’m Too Sexy.”

I missed the eyeball, but in its place I got an immersive bathroom communion with Pedro, which included audio of a man with a Pascal-ish accent telling me, “You’re my special guest, princesa,” as I washed my hands.

Branden Powers, a partner at Cantina Tequila, says he’s excited to visit Sphere once it’s open. “I’ve heard all the talk about, ‘They spent too much on this,’ but I remember that talk when the Mirage opened up,” he says. “People always bet against Vegas, but Vegas always comes through.”

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.