Move over, Barbie, it’s ‘the year of’ 92-year-old L.A. artist Barbara T. Smith

- Share via

“Me” is the simple, declarative title of a small self-portrait of Barbara T. Smith that’s suspended from the ceiling near the entrance to her absorbing retrospective exhibition at downtown’s Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

An assemblage sculpture, it features a fragment of a Time magazine cover with the “TI” clipped off, leaving just “ME” behind. A line of pink paint circles the edge of the frame and a fluffy pink feather is attached near the bottom.

The July 1964 Time magazine cover announced an inside spread on the best summer vacation resorts in the U.S. Pictured is a casually glamorous young woman striding across the shore at pricy Sea Island, Ga., hair wet and wearing a bikini. A local, not a model, the woman’s name was Michael Anderson — a somewhat uncommon gender mix.

Smith positioned the pink feather to cover the swimsuit’s bottom. It’s as if the mass-circulation magazine cover conceived of Anderson as an exotic dancer, a commercial leisure attraction framed for a readership presumed to have straight male desires.

“That’s me,” says Smith’s mirror, which is dated 1964-65.

Who Smith was wasn’t exactly clear. Then 33, daughter of a successful Pasadena mortician; married to a businessman who had been her high-achieving, high school sweetheart; mom to three kids — Smith has said she was exploring the emerging liberation movement that came to be called second-wave feminism, in which her identity would not be circumscribed as only daughter, wife and mother. A volunteer at the old Pasadena Art Museum, which was shaking things up with exhibitions of Marcel Duchamp’s Dada high jinks and Pop painting and sculpture, she was still new to art. That the little assemblage took at least six months to make suggests that the artist’s self-perception was in considerable flux.

So does her particular choice of photographic representation on the magazine cover. A bather is just about as classic as an art motif gets.

Art Center’s Ceeje Gallery exhibition shows that Ferus wasn’t the only L.A. gallery making waves in the 1960s.

One obvious explanation for its endurance is that a bather provides an excuse to show a bit of skin, giving the work a sensual kick. In Western culture, the popularity of bathers as artistic subjects tends to rise during periods of upheaval or major transition — during the Renaissance, for example, or at the end of the 19th century. Bathers have been an anchor to help stabilize major social change, all while pushing in a new direction. The subject carries a symbolic function: The bath is an act of cleansing — of starting fresh.

Sunny Los Angeles was the leading edge of bather art in the boisterous 1960s, led by British expat David Hockney, who was busy painting sumptuous pictures of men in showers and lounging around swimming pools. Smith’s more tentative but surely astute bather fits right in.

And there’s more: Since her self-portrait assemblage is suspended in space, its back is as visible as the front. The back of “Me” is encircled by a string of pearls. At the center of the oval panel is the severed head of a plastic doll. Stuck dangling from the top is a remnant of newfangled instant-camera film. Polaroid had introduced peel-apart color prints the year before, in 1963, and the do-it-yourself revolution in image-making was on.

Time magazine might offer a corporate image of feminine roles defined for a mass audience, but Smith’s savvy work seems to represent a resolve to create her own. Looking at “Me,” which I hadn’t seen before, all I could think was: “Barbie,” the movie, is super, but it hasn’t got a thing on Barbara, the artist.

Energy, beautiful and destructive, animates a powerful film by Julian Charrière in his impressive Los Angeles debut at Sean Kelly Gallery.

Organized by guest curator Jenelle Porter, the exhibition is the second installment of what T-shirts in the gift shop celebrate as “The Year of Barbara.” Now 92, Smith was the subject of an autobiographical exhibition at the Getty Research Institute — her first major museum show — that ran from February to July. The GRI holds a large archive of Smith’s papers, and it published her memoir, “The Way to Be,” covering the first 50 years of her life.

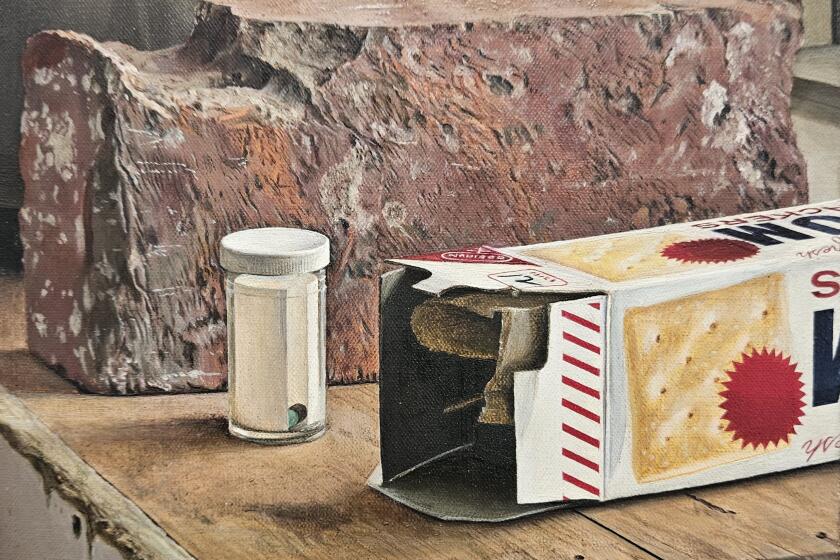

A big chunk of that archive is composed of the so-called “Coffin series” — Xerox books begun in 1966, in which Smith experimented with photocopying photographs, ordinary household objects and fragments of her own body. They’re prints, albeit made with up-to-date office machinery rather than traditional etching plates or lithography stones.

For a few years, artist Wallace Berman had been using an old-fashioned Verifax copy machine to make extraordinary art with a mysterious spiritual dimension; but the fact that his copier device represented an obsolete technology, superseded in the fast-moving world of capitalist business, was important to his spectral, mystical imagery. Smith’s art is different, given the power of mega-corporate Xerox.

Smith rented a copier, set it up in her dining room at home and made tens of thousands of Xerox prints. A large selection at the ICA shows her working against the machine’s usual office function.

She produced records of personal memories, kids’ games, domestic narratives, private snapshots, erotic indulgences and more. Anything that undermined the usual business application seems to have been the aim. For her, a family birthday party was an equivalent to the Acme Widget Co. annual report, while portraits of relatives were easily as significant as stuffy pictures of the board of directors. Even titling her Xerox books as “Coffins” is personalized, recalling Smith’s mortician-father.

Formats include thickly bound volumes, individual collaged sheets and framed grids that repeat the same image 20 or 30 times. The repetitions found in the latter motif soon would be consecrated at the Pasadena Art Museum in “Serial Imagery,” a landmark exhibition that surveyed everything from Claude Monet’s Rouen Cathedral paintings to Andy Warhol’s soup cans — but no art by any women, including Smith. The Xerox print production came to a commemorative end with “Upon the Completion of a Love Affair With a Machine,” an unassuming assemblage composed of a pastoral jigsaw puzzle piece showing grazing cows that is attached to an empty tattered box for copy paper.

The Getty exhibition emphasized Smith’s role as a pioneer in performance art, a genre so new in the early 1970s that it hadn’t yet acquired a name. The current show encompasses the full sweep of her career. The most fascinating sections survey the first 15 to 20 years as performance emerged. In the 1980s, as Smith delved deep into Eastern philosophy, her art became more obscure, while in the 1990s her production decreased, following the illness and death of her son from AIDS.

At the ICA, these and other aspects of her six-decade career are concisely organized by eight framed video flat-screens accompanied by a brief bit of explanatory text. Objects are displayed as a kind of performance residue. “Trunk Piece,” a chest stuffed with remnants from the complicated fabrication of a walk-in environment, long ago destroyed, called “Field Piece,” for example, is itself a kind of coffin.

The most beautiful physical object is surely the casting mold for a sculpture of the rind of an enormous winter squash, presented as a reliquary atop a rough-hewn altar, that was the centerpiece of an uninhibited 1971 performance. (The resin sculpture is nearby.) “The Celebration of the Holy Squash” was a weeklong feminist parody of a pious ceremony, but it took seriously a woman’s role as agent of communal ritual. The event centered on an elaborate dinner party at which guests devoured sweet Hubbard squash, a symbol of abundance and fertility, carefully prepared for consumption. The cast resin squash made gentle fun of the industrial, aerospace underpinnings of Light & Space art, which featured cast resin geometric forms. Its iridescent casting mold looks almost like a chrysalis awaiting the emergence of a monumental butterfly.

After the ritual performance, the artist placed a notice in a local legal publication declaring the formation of a new religion. Not widely known now, but a controversial work when presented as her master’s degree exhibition at UC Irvine, Smith’s playful and witty performance predated by more than three years fellow L.A. artist Judy Chicago’s fabrication of the ponderous “The Dinner Party,” her famous, altar-like installation sculpture.

The retrospective opens with three surprising paintings that suggest how Smith transitioned away from traditional objects into performances, often focused on the human body. Made in 1965, 5-square-foot canvases painted matte black are framed behind thick, reflective glass. One is edged in strips of royal blue; another sports a single tiny spot of white paint near the top; and a third features a small network of geometric color bands in a lower corner.

The “Black Glass” paintings are no doubt indebted to Duchamp’s famous “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even” (1915-23), the transparent mixed-media sculpture nicknamed “The Large Glass” that Smith encountered as a volunteer at the Pasadena Museum. Look closely, and the blackness, visually impenetrable but strangely soft, has been achieved by applying Rothko-like veils of layered pigment.

Not that looking closely is easy, mind you, since your face keeps getting in the way. The black-backed glass transforms each painting into a virtual mirror, which reflects its context — first and foremost, the person standing before it.

In them, you see yourself trying hard to see. That’s the exploratory scaffolding on which Smith constructed her most engaging art.

“Barbara T. Smith: Proof”

Where: ICA LA, 1717 E. 7th St.

When: Wednesdays and Fridays noon to 6 p.m., Thursdays noon to 7 p.m., Saturdays and Sundays 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. Runs through Jan. 14.

Info: (213) 928-0833, theicala.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.