The legend of Howdy Glenn, Inglewood’s Black firefighting country singer

Most country music fans know “Touch Me” as the song that propelled Willie Nelson to fame.

In 1962, the yearning ballad peaked at No. 7 on Billboard’s country singles chart and was the Texas native’s first hit as a solo artist. It became one of his signature songs.

But Nelson wasn’t the only singer to launch from its desirous refrain.

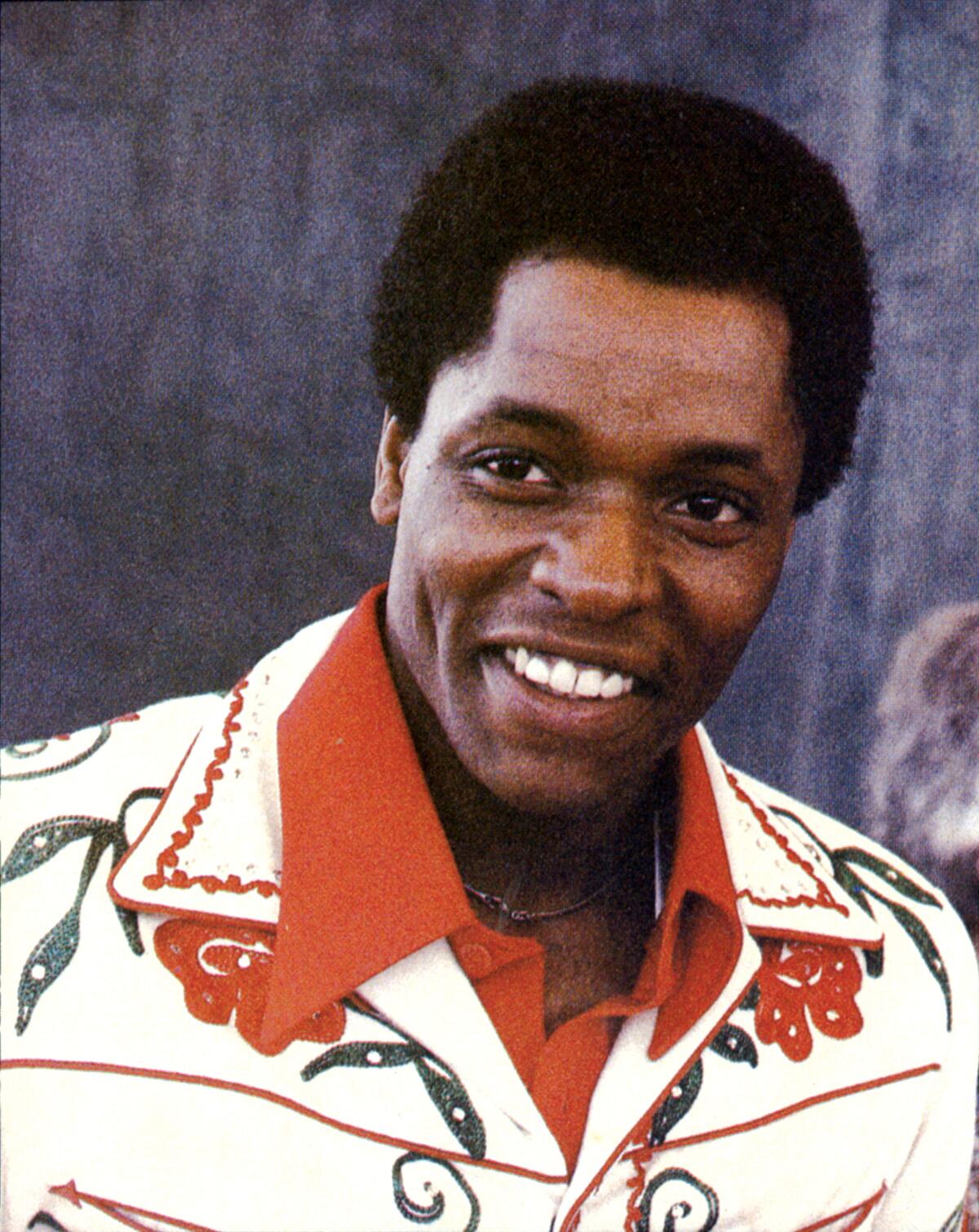

Fifteen years later, in 1972, Morris “Howdy” Glenn also made his debut on the country singles chart with the Nelson-penned tune. His version featured a powerful vocal performance, and lavish major label production.

The Inglewood resident was one of very few Black men to have success in country music in the 1970s, and one of two known Black male artists from California who performed at a nationally charting level. The other is “She’s My Rock” singer Stoney Edwards.

Unlike Edwards, Glenn (who died in 2012 at age 59) and his music were quickly obscured by false starts and the haze of time.

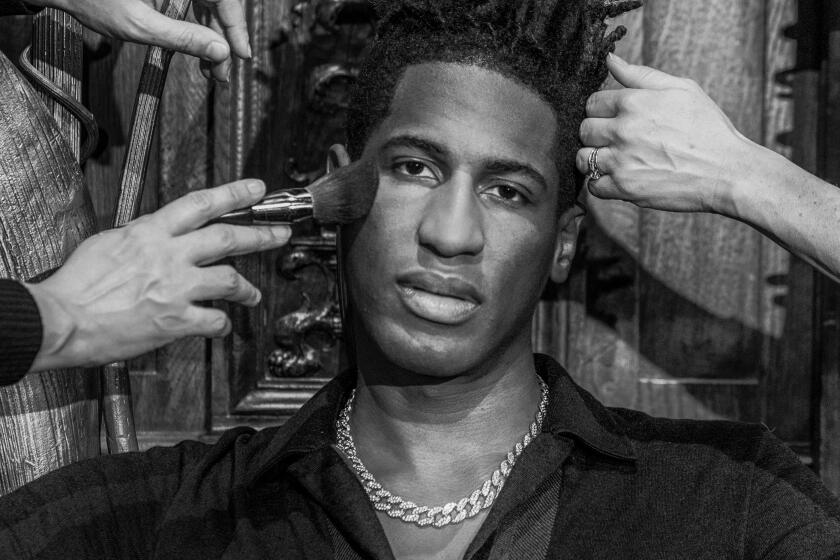

In January last year, archival record label Omnivore Recordings released the first compilation of Glenn’s work, “I Can Almost See Houston.” Its accompanying album notes, by co-producer Scott B. Bomar, are nominated for a Grammy.

“There are Black country artists who are finally getting a little attention, and finally getting their due after years of being ignored, and I thought, ‘Why isn’t this guy being mentioned?’” Bomar said of his interest in the project.

He learned of Glenn during research on a different country music artist, Oscar Whittington, a pioneer of the Bakersfield sound. The late fiddler was one of the few musicians Bomar knew who held on to decades of archival material. While sifting through Whittington’s papers, he found an 8-by-10-inch promotional photograph that included Glenn’s name and image.

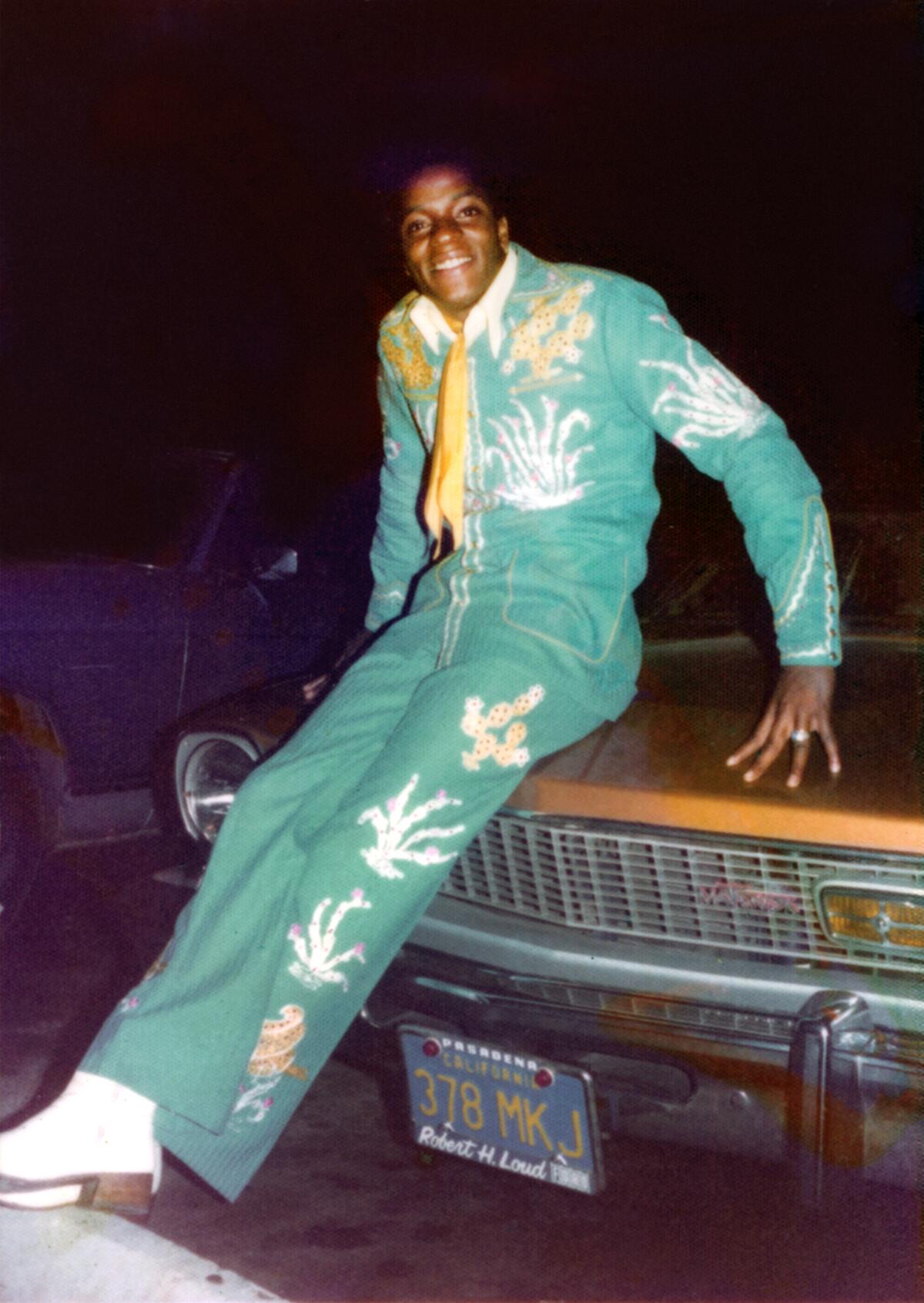

“I could tell by what he was wearing that he was a country singer from the ’70s,” Bomar said. “As someone who’s pretty deep into country music, I was shocked; I thought I was at least somewhat aware of every Black country singer because, unfortunately, it’s not a terribly long list.”

Bomar held on to the photo. In the succeeding years, he noticed Glenn’s name in a few old newspaper concert advertisements and in country music newsletters. He also realized that Glenn had been left out of the authoritative 1998 CD box set “From Where I Stand: The Black Experience in Country Music.” “I don’t think it was any kind of nefarious exclusion,” Bomar explained. “He just somehow fell between the cracks.”

Glenn was born Sept. 3, 1952, in Detroit after his parents, Willie James Glenn and Mary Glenn, migrated north from Alabama. The church was fundamental to his upbringing and was where he first sang, belting out gospel music in the choir. The family moved to Inglewood when Howdy was 19 years old, after his father accepted a ministry position at a local church. By the mid-’70s, the elder Glenn had become the pastor of the Second Mt. Nebo Missionary Baptist Church in Inglewood.

According to Geraldine Fletcher — with whom Glenn had a romantic relationship that began in 1976 and lasted most of his life — Howdy was turned on to country music by his father, who played it in the car, particularly on family trips to Alabama. “I once asked him, “What Black man listens to country western music?’” she said with a laugh. “But he had picked it up, and knew a lot of the songs and he really enjoyed it.” She said Glenn also had a collection of country music 45s and LPs by artists such as Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings that he frequently played in their home.

Glenn’s break as a country singer was the result of a dare.

By 1973, he was an apprentice with the Inglewood Fire Department. His co-workers bestowed him with the nickname “Howdy” — after the children’s television puppet Howdy Doody — due to his convivial nature. “My dad was a sweet, loving, mild-mannered man,” his daughter Itisha Sims-Reed said.

On a night out after work with his firefighter pals, Glenn entered a talent contest at a local watering hole at his co-workers’ insistence. “All firemen can do at least two things,” Glenn later said in an interview for the Academy of Country Music’s newsletter. “They fight fires, and they love country music. I’d sing around the fire station, and my fellow firefighters felt I had a special talent, and decided to do something about it.”

His cover of Tom T. Hall’s “(Old Dogs, Children and) Watermelon Wine” won first place; a local booking agent who happened to take in his performance that night signed Glenn as a client on the spot. Glenn also became a regular on the local talent contest circuit.

The Palomino Club in North Hollywood was once the West Coast’s epicenter of country music. From the mid-1950s until its closure in 1995, icons such as Buck Owens, Johnny Cash, Patsy Cline, Waylon Jennings and Dwight Yoakam played its stage.

Each week, its talent night drew lines of unknowns hoping to win a cash prize. Though the contest reportedly gave early exposure to superstars such as Linda Ronstadt, Willie Nelson and Emmylou Harris, most of its winners came and went in total anonymity.

But there were a few, like Glenn, who split the difference.

His cover of Hall’s “Watermelon Wine” earned the contest’s top honors. Along with the victory came a chance to perform at the 1974 “Trucker’s Jamboree” at the Hollywood Palladium, thrown by local then-country radio station KLAC and the Truckmaster School of Trucking.

“Easy Loving” singer Freddie Hart, and country artists Red Simpson and Dave Dudley, each known for their “trucker” songs, performed at the showcase, in addition to Glenn and two other Palomino Club talent show finalists. That evening at the Palladium, Howdy once again performed “Watermelon Wine”; he won first place and departed the venue with $500, a trophy and an audition with Capitol Records.

“That was the greatest night of my life,” he told a reporter for Country Music World in 1977. “I almost cried.” Glenn told the South Pasadena Review that he received a “personal letter” from Hall complimenting his cover.

After hard gigging in nightclubs from Los Angeles to San Bernardino, Glenn released his first single, “I Can Almost See Houston” backed with “You’ll Remember Me,” in summer 1975 with tiny Ontario-based indie Merrittorious Productions. Its A side, featuring a sophisticated-for-its-era string arrangement, and bird-like backing vocals, was remarkable for Glenn’s brawny-yet-smooth singing. It became a regional hit in several markets, including Houston, where it spent eight weeks at No. 1 on radio station KENR.

Glenn went on to record several songs for independent labels, including his own Dag-Mar and Fire labels. Some of his best recordings, such as the honky-tonk “I’m Here to Drink It All,” were written by Ray Willis, an equally obscure artist who had a minor hit when country singer Jeanne Pruett recorded his song “Welcome to the Sunshine (Sweet Baby Jane).”

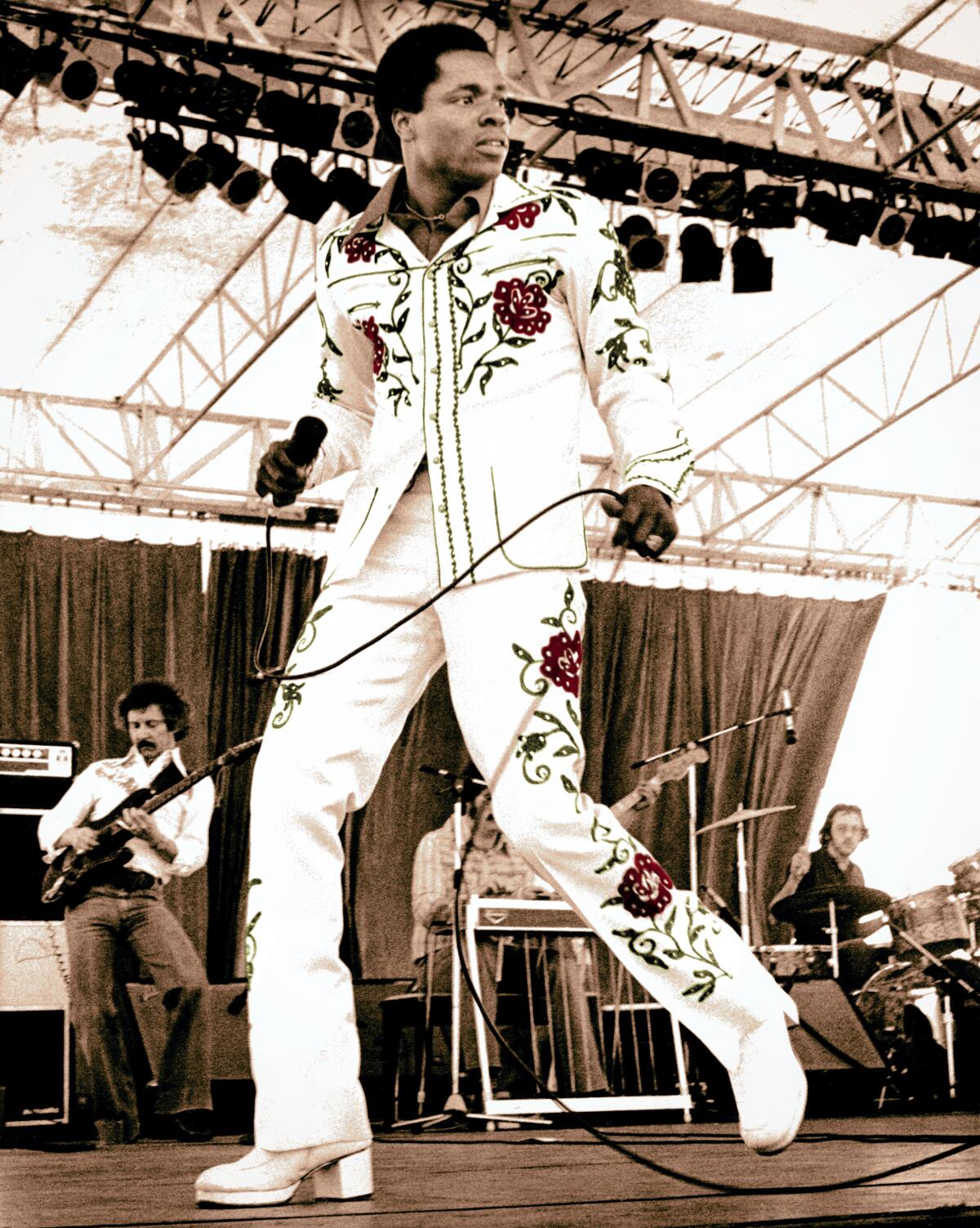

More popular than Glenn’s recordings, however, were his live performances, which were described as “causing a sensation” by the Pasadena Star-News. The country music columnist for the South Pasadena Review, Vern Nelson, responded positively to many of Glenn’s shows, calling him a “super star of the future,” in coverage from March 1977.

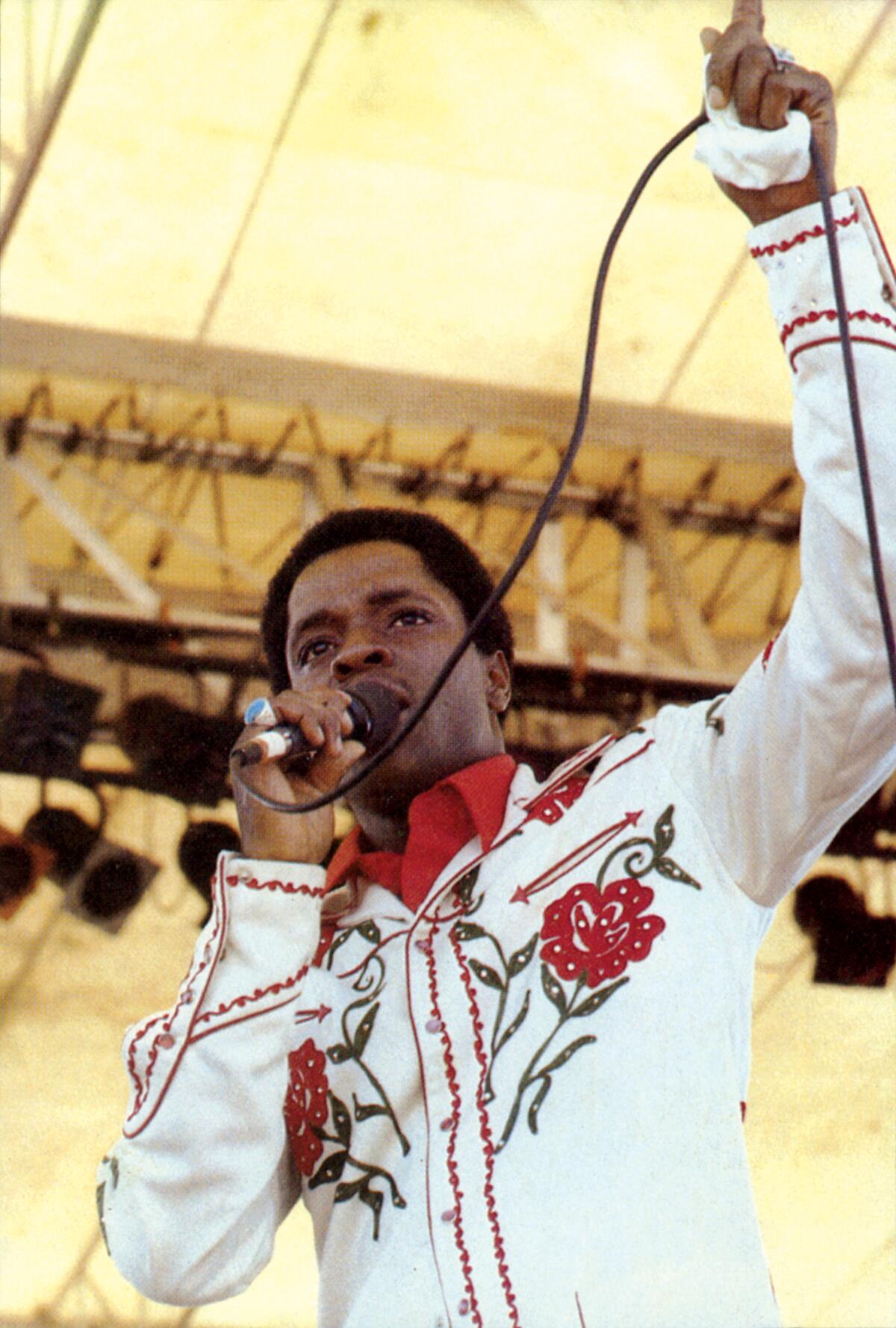

Glenn played country music clubs, but also county fairs, hotel ballrooms, benefit concerts and other community events from the South Bay to Bakersfield. “He always rocked the house,” Fletcher said. She added that stage wear was important to Glenn. A tailor in Sherman Oaks custom-made all of his western-wear suits.

Since the late ’90s, a growing reappraisal of country music — specifically its roots in Black culture — has challenged its longtime prevailing narrative.

The notion of white hillbillies as the genre’s founding class has been rethought, recontextualized and outright refuted by academics, journalists, producers and other experts, and organizations such as the Black Opry, founded in 2021 by country music fan Holly G., have sought to amplify country music artists of color through a website and live performances.

For the record:

3:33 p.m. Jan. 30, 2024An earlier version of this article described DeFord Bailey as the first member of the Grand Ole Opry. He was one of the first members and the first Black member. This version has been corrected.

DeFord Bailey, a country music star of the early 20th century, who was the first Black member of the Grand Ole Opry, has been restored as one of the genre’s important pioneers; links between country music’s founding white stars, and the Black artistry they celebrated and appropriated, have been reinforced on the basis of scholarship and other writing.

Though this conversation has grown in recent decades, its origins may be traced to foundational country music scholarship. In the introduction of “Country Music, U.S.A.,” which is widely considered the first definitive history of country music, author Bill Malone distinguishes the country genre from its white European roots due to its “influences from other musical sources, particularly from the culture of Afro-Americans,” and asserts that, “country music — seemingly the most ‘pure white’ of all American musical forms — has borrowed heavily [from African Americans].”

As important as the singer Charley Pride is to the genre, there is much more historical Black presence and influence in country music than the decorated Mississippi native. But in the ’70s, there remained a narrow-mindedness about how many Black men should participate. According to Bomar’s album notes, Glenn recounted this mind-set to the journalist Janice Smith. Early on in his career, Glenn said he was told that he’d “never amount to anything” because “we already have Charley Pride” and “one was enough.”

Despite such prejudice, by the spring of 1977, local Howdy Glenn buzz had grown so strong that Warner Bros. country music A&R man and producer Andy Wickham signed him. (It’s unclear if he ever auditioned for Capitol Records.)

“The fact that he was African American, we didn’t really focus on that,” said Bob Merlis, who headed the publicity department at Warner Bros. for three decades. Instead, they drew on his career as a firefighter, positioning him as “the singing fireman.” They ran print ads with Glenn in his uniform with the tagline “Warner Country Is Smokin.’”

Merlis was also struck by Glenn’s friendly demeanor, particularly during their first meeting. “As if to make conversation or sort of break the ice, he took me aside and said, ‘I got a new van recently, and I’m enjoying the hell out of it,’” Merlis remembered with a laugh. “No context whatsoever, just said that. I think he just wanted to connect.”

Glenn recorded three songs in his first session for Warner, the ballad “Don’t Take Pretty to the City,” “White Line Fever” by Merle Haggard and “Touch Me.” The latter marked Glenn’s entry into the country music charts, peaking at No. 62. It was remarkable given Glenn’s background, but it wasn’t a runaway hit. His version of “You Mean the World to Me,” also released by Warner, reached No. 72 on Billboard’s country singles chart in July 1978.

Like many artists who sign to a major label after a flourishing independent career, Glenn struggled within the system. He enjoyed the process of arranging songs, for example, and was good at it, but was stonewalled when he tried to participate. He also felt like Warner wasn’t bringing him the material he deserved, as evidenced by his recordings of songs such as “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” “America the Beautiful” and the pop standard “That Lucky Old Sun.” He never released a full-length LP for the label.

Fletcher explained that she wasn’t closely involved with Glenn’s fallout with Warner Bros., but she did notice a major shift in her formerly affable partner. “I just know his demeanor changed,” she said. “He would get somewhat depressed because he had music and it was good, but he couldn’t get it out there.”

Glenn was so discouraged by the experience that he kept his job as a firefighter the entire time he was signed to the major. After he left, sometime around 1980, Glenn began working his way up to the engineer position, becoming the first Black man to do so at the Inglewood Fire Department. He spent the latter part of his career as a tillerman, steering the rear part of a big red truck.

Of the renewed interest in her father’s music, Glenn’s daughter Sims-Reed said her father put his all into his music and this is what he always wanted. “I just wish he was here to see what’s going on and how things are manifesting,” she added. “This is a super proud moment for me and my kids.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.