- Share via

I spent much of the first months of 2020 driving around America, before spending almost every day of the next 10 sitting right here. The occasion was a reunion tour with a singer-songwriter I accompanied through the 1990s and into the early 21st century, the artist formerly known as John Wesley Harding and now by his own name, Wesley Stace. As my Twitter bio says, “L.A. Times TV Critic. Sometime sideman.” This was that sometime.

(Note: I also kept up TV criticism during the tour, because that is a thing you can do now, with the Wi-Fi and laptops and smartphones and such, and there is a lot of downtime in these situations.)

Los Angeles Times television critic Robert Lloyd chooses the best TV shows of 2020.

It seemed a mad thing to be going out driving in the dead of winter, when there was every chance of sleet and snow to stay us in our appointed rounds. I could tell you stories: New York to Boston, 1996; Cleveland, 2001; Fourth of July Pass, 2002. The nearest I have ever been to death is in a moving vehicle on tour. (On bus tours, trying to sleep in a bunk that would make a coffin feel roomy, I would sometimes think about the old or overweight bus driver, driving overnight, and surrender my fate to the universe.) Yet, except for a few bad hours in Nebraska, crawling along in the tracks of semis as the road disappeared under a blanket of white, we were lucky with the weather — and doubly lucky in that, having not waited for warmer days, we managed to finish the tour just before everything shut down.

When I was a youngster, my father spent years working for and sometimes traveling with a Famous Rock Band, which seemed to me the most romantic thing possible. I hit that road relatively late but over the course of 15 years went out regularly, mostly with Wes. The first time we toured together was with an electric band in which I played keyboards, with a bus and road crew and major-label dudes coming out to buy dinners on the artist’s dime (the magic of the recoupable advance). There would be other, more modest band tours a decade later, but most of the time we traveled as an acoustic duo (him: guitar and singing; me: mandolin, accordion and piano, wherever one was waiting), splitting the driving.

Though it had been a dozen years since I had embarked on a tour of any length and 17 since Wes and I were really on tour — we have played together here and there in the interim — it didn’t take long to ease into the old patterns, riding along in comfortable silence and playing each other things on the stereo. (On this trip I was acquainted with two radio dramatizations of Anthony Powell’s 12-volume “A Dance to the Music of Time,” Andy Stanton’s brilliant readings of his highly original “Mr. Gum” children’s books, episodes of the BBC radio comedy “Count Arthur Strong” and the experimental classical folk jazz of Frisk Frugt.) Sometimes we would talk about the Arsenal football club — Wes is from the U.K. and a supporter — which was also an old pattern. It is all pretty civilized; we are mature gentlemen, with alternate income streams: Wes writes novels and was even then, as I rolled along, at work on an opera libretto for British composer Errollyn Wallen. And I do … this. So the music was pure gravy.

Movement is historically, for better and for worse, the American way. The size and even the shape of the country, with its latticework Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, almost encourages it: You can hop on the 10 in Santa Monica and ride it all the way to Jacksonville, Fla. (though they probably just call it “10” there), or take I-80 from San Francisco Bay to the Hudson River. So why wouldn’t you? But it is an older story than that, baked into our culture and history and our romanticized notions of freedom — Route 66 and Highway 61, “Easy Rider” and “On the Road,” “It Happened One Night” and “The Wizard of Oz” (a yellow brick road movie) and innumerable tales of wagon trains and railroads and the whole awful enterprise of “America” bullying its way from sea to shining sea.

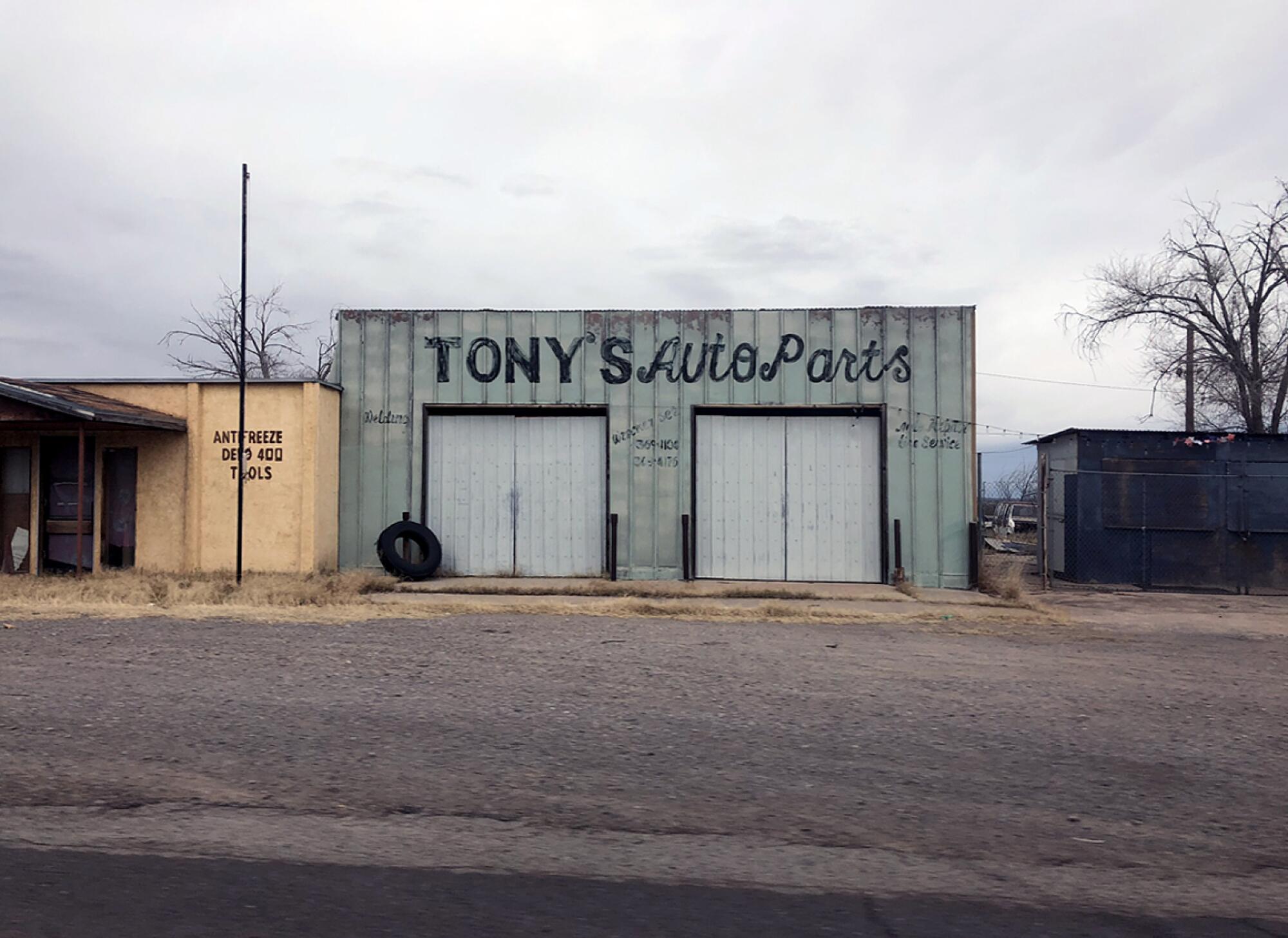

We began the tour by fast-forwarding that westward expansion, meeting in Philadelphia, where Wes lives now, to briefly rehearse, then driving to Austin, Texas, for the first show, Tucson for the second and Newport Beach for the third. There is a difference between stepping onto an airplane on one coast and getting off on another, with nothing but five or six hours in a sealed tube in between — an ordeal but not an accomplishment — and going by land, as one landscape gives way to another, deserts to mountains to prairies to hills. The first time I did it, traveling back from college, felt like a rite of passage, a 3,000-milestone. I have done it many times since, in the north, in the south, down the middle, and it was good to be back. There were old friends to see along the way and sometimes to play with.

Some things were different. Getting lost, an unavoidable feature of 20th century touring, is nearly impossible in the 21st; if you miss a turn, your GPS will recalculate your route before you can say, “We missed that turn.” Smartphones (and the texted advice of our Chowhound-rocking friend Lacy) allowed us to find good restaurants in Knoxville, Tenn. (Oliver Royale), and Las Cruces, N.M., (La Posta de Mesilla) and guided us to Carhenge in Alliance, Neb., a to-scale, solstice-aligned model of Stonehenge made from old cars.

Contestants on “The Great Grass Race,” inspired by Lynch’s “The Straight Story,” encountered American generosity — plus infighting, disorganization and danger.

But there were still surprises. Indeed, pop touring has the advantage of taking you places you’d never think of going in the normal course of travel; you surrender to the itinerary and take what comes. We could not have predicted that the west Maryland mountain town of Frostburg, and its unexpected bohemian cafe/venue Clatter, would be a trip highlight, or how delightful it would be to be put up by the soap-making nuns of the Episcopal Carmel of St. Teresa in Rising Sun, Md., or the “Alice’s Restaurant”-ness of Mor Pipman’s preshow spread at the Old Glenford Church. “America is hard to see,” wrote Robert Frost, in a line Wes quoted in a song called “Robert Frost Rag,” unless you get right out into it.

It was a motley trip. At one stop, we played for two friends (it was their house), their dog and two strangers. Elsewhere, houses (actual or theatrical) were packed. Chicago (Evanston, to be precise), being an old stronghold, was full, as were New York and Los Angeles — or, to be precise again, Santa Monica, at McCabe’s, a local home base where Bruce Springsteen sat in with us back in 1993. (Oh, sorry, I didn’t mean to mention that.) We played two desanctified churches (Portland, Ore., and just outside Woodstock, N.Y.); an art gallery in Roanoke, Va.; the the Arden Gild [sic] Hall, a volunteer-run community center in a 120-year-old Delaware artists colony; old rock joints like the Saint in Asbury Park, N.J.; and the Rosenbach Free Library in Philadelphia, known for its manuscript copy of James Joyce’s “Ulysses.”

House concerts — just what they sound like, a concert in a house, and for the foreseeable future a terrible, not to say terrifying idea — had become part of the mix since our last tour together; indeed, they were the glue that made the whole thing feasible and stretched it, astonishingly, to 33 dates. You know pretty much what to expect in a club or a hall, give or take a few microphone inputs or PA mixes or whatever food and drink materializes or doesn’t backstage. But most every house concert was … original. (In Columbus, our opening act, so to speak, was the son’s college glee club. It was excellent.) A few were semiprofessional, stops on a regular circuit; more, answering an open call from Wes to fans, were unpredictable, sometimes arranged with more enthusiasm than care but all with a personal touch. Usually we would just play into the air, without amplification, and, generally speaking, they were as fun to play as club dates, though the crowd might be more familiar with the hosts than with the music.

By the last weeks of the trip, the idea that the virus was present everywhere had crept into the national consciousness but not to the degree that we hesitated going into a bar or a cafe or stepping into an elevator with strangers. Social distancing hadn’t entered the lexicon, only the idea that you should stay away from the sneezers and the coughers and wash your hands a lot. (Lady Macbeth had nothing on me.) Elbow bumps were practiced by the thoughtful, if with a hint of embarrassment, but masks hadn’t even entered the picture. The danger posed by asymptomatic carriers was not yet established nor was aerosol transmission well understood. And at shows, we were typically the safest people in the room — backstage, usually on our own, onstage six feet or more away from the audience. Afterward could be a different story: the outstretched hands, the selfies, the merch. It was early days, corona-wise, but we were just lucky not to run into the wrong person.

We polled more than 40 TV critics and journalists, inside and outside The Times, on the best TV show to binge while stuck at home.

The week I returned home, from an eerily empty Philadelphia airport on a plane one-third full, was the week the curtain came down. Every day I counted back 14 days to whatever crowded place we’d been in, until it became clear that I hadn’t gotten sick, as far as I could tell, and so had likely made no one else sick. And then it was just a matter of relaxing into the new reality. There was a sense at first that people might take it seriously enough to do the little it would require to break the chain of infection, and we would be through it relatively soon. But this is a big country — see above — and well, you read the papers. In order to feel “free,” the nation has laid itself out as a banquet, rung the dinner bell and crowded as many plates as possible around the table. And so here we are.

Of course I would like to be out moving again. When every day you go to sleep in a different city than the one you woke in, time expands — it’s the opposite of the housebound routine, when a weekly Zoom meeting comes around and it feels like two days since the last one. At the same time, the pandemic can make you more aware of the ticking clock, the sand running through the hourglass. And so, in the spirit of January and February and a little bit of March, I try to remember to make things besides the things I make for work, to flex that muscle, like remembering to exercise. (You may have seen my cat drawings in these pages.) I write music for my computer to play. It’s its own reward. All gravy.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.