MOCA celebrates 30 years and a rebirth

The financial chickens came home to roost at the Museum of Contemporary Art a year ago, but on the eve of what’s being dubbed “MOCA New,” a 30th-anniversary celebration centering on the museum’s biggest exhibition ever -- drawn almost entirely from its own collection -- museum leaders want to prove to the public that those birds have flown.

FOR THE RECORD:

MOCA: An article in Sunday’s Arts & Books section about the Museum of Contemporary Art referred to “a Mark Rothko bull’s eye” painting in the museum’s collection. The painting is by Elaine Sturtevant, based on a target image by Jasper Johns. —

Nevertheless, as chief curator Paul Schimmel planned the show, “Collection: MOCA’s First Thirty Years,” he and artist Andrea Zittel mulled whether to house eight bantam hens in her conceptual piece, “A-Z Breeding Unit for Averaging Eight Breeds” -- as the sleek, steel-and-glass, climate-controlled henhouse-as-inverted-pyramid did when it first was seen in 1993.

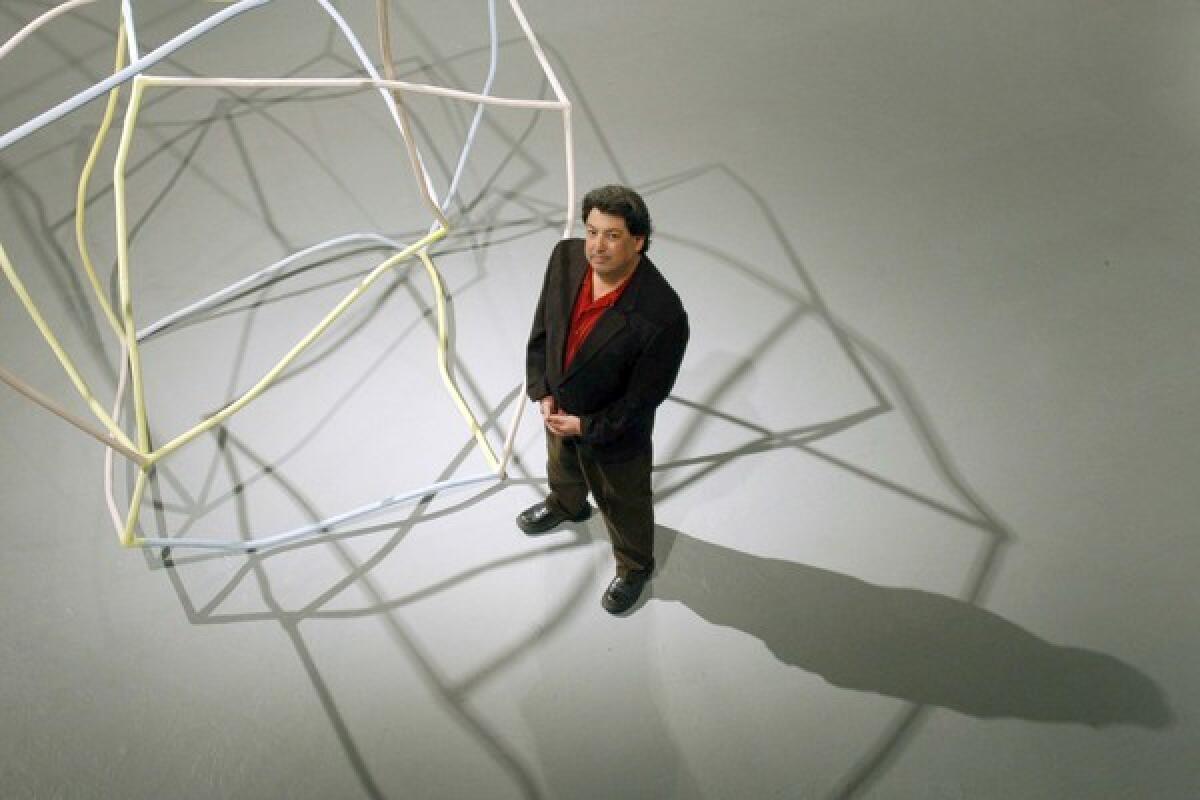

Zittel was game, Schimmel said, but she worried that the birds would be too cooped-up during a show scheduled to run nearly six months and proposed creating a new, roomier version. Schimmel decided viewers at MOCA’s Geffen Contemporary building, which will reopen after being dark 10 months to save money, would have to be satisfied with the existing structure, sans hens. “This,” joked the talkative, tousle-haired curator, “is the new, more economically viable MOCA.”

Large as it is, the anniversary display spares MOCA the expense of importing art, except for five paintings borrowed locally from the Broad and Weisman foundations. But the show, which occupies all of the Grand Avenue headquarters building and half of the Geffen Contemporary to the east in Little Tokyo, offers the deepest and broadest gaze presented of the museum’s collection.

It ranges in time from a 1939 painting by Piet Mondrian to works created in 2006. Among the newest are Charles Gaines’ “Explosion Drawing #7,” a billowing inferno that could be the flame-and-smoke flowering of a suicide bomber’s belt or an improvised explosive device.

MOCA’s fiscal crisis wasn’t just a product of last year’s global meltdown. It followed nearly a decade of chronic fundraising shortfalls, during which museum leaders steadily spent down a $38-million endowment to continue the ambitious exhibitions that helped cement its reputation for presenting perhaps the world’s finest roster of shows dedicated exclusively to post- World War II art. When the worldwide economic woes hit, they left MOCA nearly tapped out.

Finally, the board accepted a $30-million bailout from Eli Broad, whose conditions included trustees escalating their own contributions, while putting a lid on spending. Nine months later, museum officials announced that nearly $30 million in additional pledges and donations had come in this year, including $2 million from board member Fred Sands.

With director Jeremy Strick forced to resign, Charles Young, the former UCLA chancellor, came out of retirement to shepherd change. By June, he and the board had cut staff and spending 25%, yielding a museum with a $15.5-million budget and 119 employees. The recruitment of several new board members and the return of two who left around the time of the crisis are signs that at least some wealthy funders are buying into the plan.

Young hopes to give way by March to a new director being sought with help from an executive search firm hired in September.

MOCA recently began buying art for its collection again after a six-month freeze, Young said. The museum’s most significant purchase was its $11-million acquisition of the Panza Collection in the early 1980s; the 80-work trove of Abstract Expressionist and Pop-era art heralded the young museum as a force in the contemporary art world.

The collection has grown from there mainly through gifts. Over the years, major donations of art collections have come from Marcia Weisman, Barry Lowen, Scott Spiegel and Rita and Taft Schreiber, the Lannan Foundation and through funding from the Ralph M. Parsons Foundation.

“Having the collection up” -- as in the anniversary show -- “is by far the most successful way of soliciting individuals to make donations,” Schimmel said.

As the museum banners its 30th-anniversary gala and exhibition (the party on Saturday is being directed by artist Francesco Vezzoli and includes a one-off performance piece he’s conceived for pop singer Lady Gaga and dancers from the Bolshoi Ballet), the aim, said Young, is to show “that MOCA has turned itself around, MOCA is out of survival mode, and is self-sustainable and moving forward.”

But MOCA still has work to do before many in the art world are convinced it is really back, says Lyn Kienholz, founder of the L.A.-based California/International Arts Foundation, which aims to raise the profile of California artists.

In her circles, Kienholz said, “everybody’s feelings are on hold” as to whether the museum can muster the funding and nerve to jump back into the expensive game of regularly booking touring shows and organizing ambitious homegrown special exhibitions.

The shows that allowed MOCA to make its name typically have relied on intensive curatorial research to scout, study and borrow outside artworks, then the added expense of shipping, insuring and installing them. “They’ve done a fabulous job over the years,” Kienholz said, “and we hope it will continue.”

At the moment, the exhibition larder at MOCA’s two downtown venues is thin, with only a traveling Arshile Gorky retrospective announced.

Memory lane

Walking with Schimmel through the mazes of galleries in the Geffen and on Grand Avenue, and listening to him describe the thought process behind presenting the art, it becomes apparent that this is the box-set version of MOCA, intended to show how art has developed since World War II but from a perspective uniquely L.A.’s.

For him, after nearly 20 years at MOCA, going through the collection to pick this array of its finest works was like going through old school yearbooks. Along with the pieces themselves, he says, what kept hitting him were the voices and sensibilities of the artists, collectors, curators and museum leaders who shaped the collection.

“Far more voices have played a role than I understood,” he said. “There’s a patchwork of visions. You say, ‘Aah, there’s Ann Goldstein’s there [the senior curator who recently left to become director of an art museum in Amsterdam], there’s Richard Koshalek’s, there’s Pontus Hulten [MOCA’s first two directors], there’s [collector] Barry Lowen, who passed away [24] years ago. You recognize the presence.”

Art, it has been said, is news that remains news. For Schimmel, a big part of curating this show was arraying works in ways that help them continue to speak freshly, not just to the viewer but to one another.

MOCA’s curators don’t take the layman’s approach to hanging paintings -- put ‘em on the wall and see how they look. They get to play with dollhouse versions of their own buildings, which they filled, in laying out this show, with hundreds of tiny, lovingly detailed replicas of the works that were finalists for inclusion.

One model is in the basement of the Grand Avenue building, near the center of a high-ceilinged storeroom, staging and office area so packed with art awaiting installation upstairs that it made one think of the hoard at the end of “Citizen Kane” -- minus the sled.

In the storage section, two gaunt, towering Giacometti statues stand side by side, carefully anchored and belted with protective padding. Schimmel pulls on a sliding wall used for storing paintings, and a Jasper Johns, a Mark Rothko bull’s-eye, an Elaine Sturtevant and two Franz Klines materialize.

Later, while fiddling with the exhibition model, Schimmel blithely commits the art crime of the century, plucking Jackson Pollock’s “Number 1, 1949” drip painting from the wall with a loud snap and rubbing its edges between his thumb and forefinger. The real item, a 5-by-9-foot storm of color and light, is quite safe and will hang in a gallery above.

Schimmel suggests that viewers make at least two visits to take in this show. First do Grand Avenue, which brings you from the 1940s through the 1970s and includes such stars as Willem de Kooning, Andy Warhol, Diane Arbus, Roy Lichtenstein and Robert Rauschenberg. Then return for the 1980s onward at the Geffen. As the clock moves forward, the presence and influence of L.A. artists increase.

“This is very interesting. CalArts, CalArts, CalArts,” he says while escorting a visitor through the Geffen. He’s ticking off the common pedigrees of three artists, Lari Pittman, David Salle and Jack Goldstein, on show in one gallery. Then he points toward an adjoining room and says, “Mike Kelley, CalArts. You can’t overstress the importance of CalArts in the ‘80s.”

Mortality on display

A little farther on, he stops and seems suddenly taken aback. He’s just showed “Portrait of MOCA,” a conceptual piece by Felix Gonzalez-Torres in which the titles of key exhibitions in the museum’s history form a two-line printed crawl near the ceiling, along with references to world-historical events. Nearby are a painting by Martin Kippenberger and a space reserved for a not-yet-hung canvas by Goldstein.

“All artists my age or younger, who died,” says the curator, 54. “It just dawned on me. If I had realized it before, I probably wouldn’t have put them together.”

Mortality is an intended part of the story in another gallery, where drawings by Raymond Pettibon face “Swedish Erotica & Fiero Parts,” a large conceptual art installation by a fellow Angeleno, Jason Rhoades, who died in 2006 at 41. “He was very close with Raymond. They owned a fishing boat together,” Schimmel says. “Does that mean anything to the public? I don’t know. I know it’ll mean something to Ray and to [Rhoades’] widow. It’s one of the great stories throughout the history of art, the relationship between artists and the dialogue as they do different things.”

If you wend through the 70 years of artists’ affinities and contradictions, desires and revulsions, measures and countermeasures, Schimmel says, “You will have a very full and rich story -- not the only story -- but a very full and rich story told from the vantage point of Los Angeles.”

It’s probably for the best, he says, that MOCA’s money problems “played out in a very public way, because sometimes when you think you might lose something, you appreciate it more. If there is anything that will make people aware of how substantial this museum is, how much it has accomplished in 30 years, it’s the permanent collection show.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.