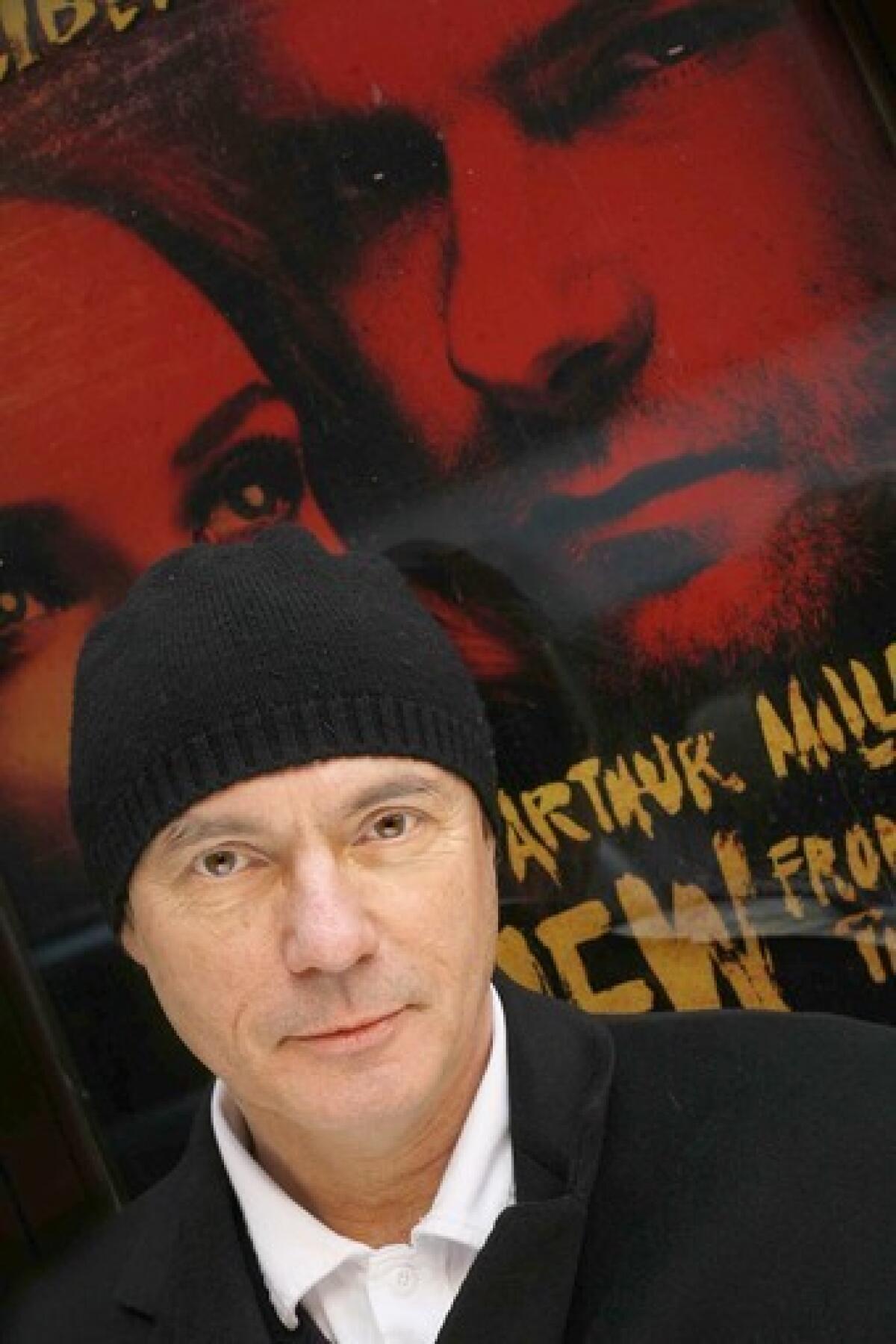

Director Greg Mosher’s view from a new ‘Bridge’ is clear

Reporting from New York — Scarlett Johansson is set to step before a Broadway audience for the first time Monday night in Arthur Miller’s waterfront tragedy, “A View From the Bridge,” in the role of the 17-year-old niece of a tough New York longshoreman whose feelings for her carry him and his family to a shattering end.

Johansson’s debut in Monday’s preview is getting more attention than a notable reappearance, the return of Gregory Mosher, who last directed a Broadway show 17 years ago -- “A Streetcar Named Desire,” starring Alec Baldwin and Jessica Lange.

In the years leading to that production, Mosher produced about 200 shows and directed about 60. His was one of the defining directing careers of an era: 23 premieres of Mamet plays and adaptations, and through his direction of the Goodman Theatre in Chicago, he brought national prominence to the tough-toned Chicago style.

In an essay David Mamet wrote about him, titled simply “Greg Mosher,” the playwright describes what makes Mosher such a valuable collaborator: “Mosher’s skills are based on respect for the text, the cast, and the audience.”

During his six-year tenure as artistic director of the Lincoln Center Theater, he mounted award-winning productions of “The House of Blue Leaves,” the musical “Anything Goes,” and a searching revival of “Our Town,” which he directed.

Then --

“Yes, yes. I stopped. I stopped. I stopped!” Mosher erupts. “I ran a very successful theater, probably the most high-profile theater in America, and I stopped! And now you want to know why I stopped. That’s your next question, isn’t it?”

Mosher’s voice, turned loud by his memories, stops. He holds his dark eyes on me from beneath a blue wool cap he’s tucked over a clean-shaven skull.

He glances at the ceiling of the 97-year-old Cort Theatre, where “View” will open Jan. 24, after previews. We sit on stairs rising from the mezzanine to the balcony. Through open theater doors, sounds rumble from a stage where a rehearsal is about to start. Lighting cues for John Lee Beatty’s set of dark red apartment buildings -- “impressionistic yet realistic, not kitchen-sinky,” the director says of his friend’s work -- are put through their early paces.

“I was tired,” the 60-year-old Mosher says quietly. “I would walk into a door because I forgot to open it, I was so tired.” He never gives an definitive answer. He searches for one, then another, as if still searching himself. At one point, he asserts that differences with his Lincoln Center partner, Bernard Gersten, did not drive him out, a lingering rumor that Gersten also dismissed in a separate interview. Mosher also says a published comment he made that theater was dying doesn’t explain it. He says he made “the leap,” as he calls it, to get “away from the intense but narrow piece of the pie that is the American theater.”

He says, sighing: “I think I had Peter in the back of my mind.” Peter is director Peter Brook, a legend of revolt in theater-making that was also a return to essentials and a man Mosher knows well.

Brook’s book “The Empty Space” had a big influence on Mosher and others when it was published in 1968. His image of a bare stage as a sufficient setting to make theater took root in Mosher’s mind as a metaphor for how to direct one’s life. “It’s about more than theater. It means that one has to retain the ability to strip away old approaches and start again.”

When he took the leap, he says, Brook set an example as someone who alternately worked inside of important institutions --the Royal Shakespeare Company -- and ventured out to test ideas.

Mosher first landed with Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign, for which he says “I wrangled celebrities” and worked on “the atrociously named event called Broadway for Bill.”

“I love to plunge into situations that are inchoate and uncertain,” he says. He worked with the famous and the not famous, had good luck and bad, wrote a screenplay about a Nabokov novel that never got made and made a movie with Ed Harris and Wallace Shawn called “The Prime Gig” that did -- but went straight to DVD.

He did a stint running the much-troubled Circle in the Square Theatre, produced “Freak,” John Leguizamo’s one-man hit, and a retelling of Ovid’s transformative tales called “Metamorphoses,” which theater-artist Mary Zimmerman staged using a swimming pool on stage.

An eclectic mix of projects

Mosher, a physician’s son who grew up in Ithaca, N.Y., and studied directing at Juilliard, says ironing out his chronology is hard. In 2003, when his agent called him to go to Denmark to direct Edward Albee’s “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” in Danish, he went -- “because I didn’t speak Danish!”

In 2004, the Kennedy Center asked him to direct Tennessee Williams’ “The Glass Menagerie,” with Sally Field as the matriarch Amanda Wingfield. It won raves and might have been Mosher’s return to Broadway if not for an obstacle involving the rights.

Field says “we were all disappointed” it didn’t get to New York. She calls her work with Mosher a “remarkable experience,” while finding his reluctance to give specific guidance “maddeningly idiosyncratic.”

“He wanted us to do it without leaning on him. Halfway through the run,” Field says, “the three of us were talking and said: ‘What a fantastic thing Mosher has done in how he’s led us to become this dysfunctional family.’ ”

Mosher says: “Many actors are more used to more guidance than I give them. I told her she was ready for opening night at the third rehearsal. I think that scared her. People say directing is 90% casting. That’s wrong. It’s 96%.”

That year, Lee Bollinger, the new president of Columbia University, asked Mosher to start a program to bridge the school’s campus and the realm of the arts. Mosher took Bollinger’s invitation to make Columbia an artistic-academic laboratory.

He remains director of the Columbia University Arts Initiative, which these days focuses more on special pricing methods and the Internet to draw more students from Columbia and other New York schools to the arts.

He says he chose “A View From the Bridge” “because I admire its directness. I admire its emotional power.” He turns away questions about current political contexts -- the play’s romantic hope meshes with an act of informing against two illegal immigrants. “I have to do this. I just think I have to do just this. And I’m a lucky guy and I have found actors who will let me do this.”

He says he was intrigued by the play’s evolution, from the stark version that appeared in New York in 1955, to the longer version that is still performed, which was staged by Brook in London in 1956.

Casting the play

The show formed in Mosher’s mind long before the cast stepped into an empty Manhattan rehearsal space a month ago. He got the rights from Rebecca Miller, the playwright’s daughter. A lead producer, Stuart Thompson, says he got onboard “because of Gregory.”

He brainstormed ideas with Liev Schreiber, who plays longshoreman Eddie Carbone, before meeting with Johansson, because “you have to build your production around Eddie Carbone, it’s his story.”

Then he flew to Los Angeles and spent three hours talking with Johansson, a 25-year-old who gained her stardom through film work. “She auditioned me as much as I auditioned her,” he says.

Mosher says he was not compelled to cast a star as an investment. “Sure, you can cast Al Pacino and Meryl Streep and you can hope that works out for you financially, but that doesn’t work for me,” he says. “I have to do it because I love it.”

He cast Johansson after watching her films repeatedly, listening more than he looked. “It was the voice,” he said. “That throaty, husky voice. It’s not the squeaky voice of a girl.”

In a 90-minute play, Johansson’s character must unfold from adolescence to adulthood. Mosher says she will do well. “People have asked me what I most admire about Scarlett, and I say, ‘It’s courage.’ She takes chances. She has that quality of an actor who plants her feet on the stage and tells the truth.”

It’s what Miller looked for, Mosher said, and he knew Miller well. He spoke of the playwright by cellphone, while standing onstage during a break in which the actors ate dinner before work that would go on until midnight. Miller, he said, had a ritual of buying a new pair of shoes before going into rehearsal with every new play. He said he once heard a remark from the writer of “Death of a Salesman” that the rehearsal process “was like being reborn.”

Then, Mosher’s tone jumps. “I’ve got to go,” he announces, in the way of someone returning to larger duties. “People are coming back. We’re about to begin.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.