Andre Previn’s ‘Streetcar’ opera will play L.A., but without him

Reporting from New York — When you enter the small sitting room in André Previn’s Upper East Side apartment, the cluttered space resembles a virtual survey exhibition of the 85-year-old composer’s far-flung career and personal life.

In plain sight on a table in the back were his four Academy Award statuettes — the first he won for “Gigi” in 1959 and the last for “My Fair Lady” in 1965.

To the left stood floor-to-ceiling bookshelves overflowing with orchestral scores, some of them for his own music. After leaving Hollywood in the late ‘60s, Previn dedicated himself to classical music and served as music director of the London Symphony and Los Angeles Philharmonic. Near the window, photographs of his extended family were arranged in a jumble: children, ex-wives (he’s had five, including actress Mia Farrow and violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter) and grandchildren.

After a few minutes, Previn made his entrance. He was using a walker and was helped to his seat by a personal aide. If he appeared physically frail, he soon proved mentally sharp. In a wide-ranging interview, he was by turns quick-witted, acerbic, humorous and ruminative. On this day, he was dressed in a sweater and slacks, his gray, thinning hair combed back.

“It’s strange that none of my kids are musically talented,” he mused when asked about the family photographs. “Well — my youngest son, Lucas, he’s a wonderful rock guitarist. It’s the kind of music I can’t stand. But he’s very good at it.”

Previn was seated in an armchair beneath a series of posters for his opera “A Streetcar Named Desire.” The work, which premiered in San Francisco in 1998, will be performed at Los Angeles Opera starting Sunday, with Renée Fleming reprising her role as Blanche DuBois.

“I always thought that the play was really an opera but with the music missing,” said Previn, who worked with librettist Philip Littell to adapt the Tennessee Williams play for the operatic stage. “I don’t know why more of his plays haven’t been turned into operas. They are all excellent — every single one of them.”

The composer was commissioned by San Francisco Opera, and he wrote the piece with Fleming in mind for Blanche. When it debuted, the production received mixed reviews, some of them harsh. Previn’s score is often characterized as lush and romantic in the old-Hollywood style, and it features some show-stopping arias, including “I Can Smell the Sea Air.”

The opera has been described as having New Orleans jazz influences, but Previn bristled at the suggestion. (The composer was a jazz pianist for years but has largely given up that facet of his career.)

“That would be a little too obvious, don’t you think?” he said. “But if you seem them there, that’s fine.”

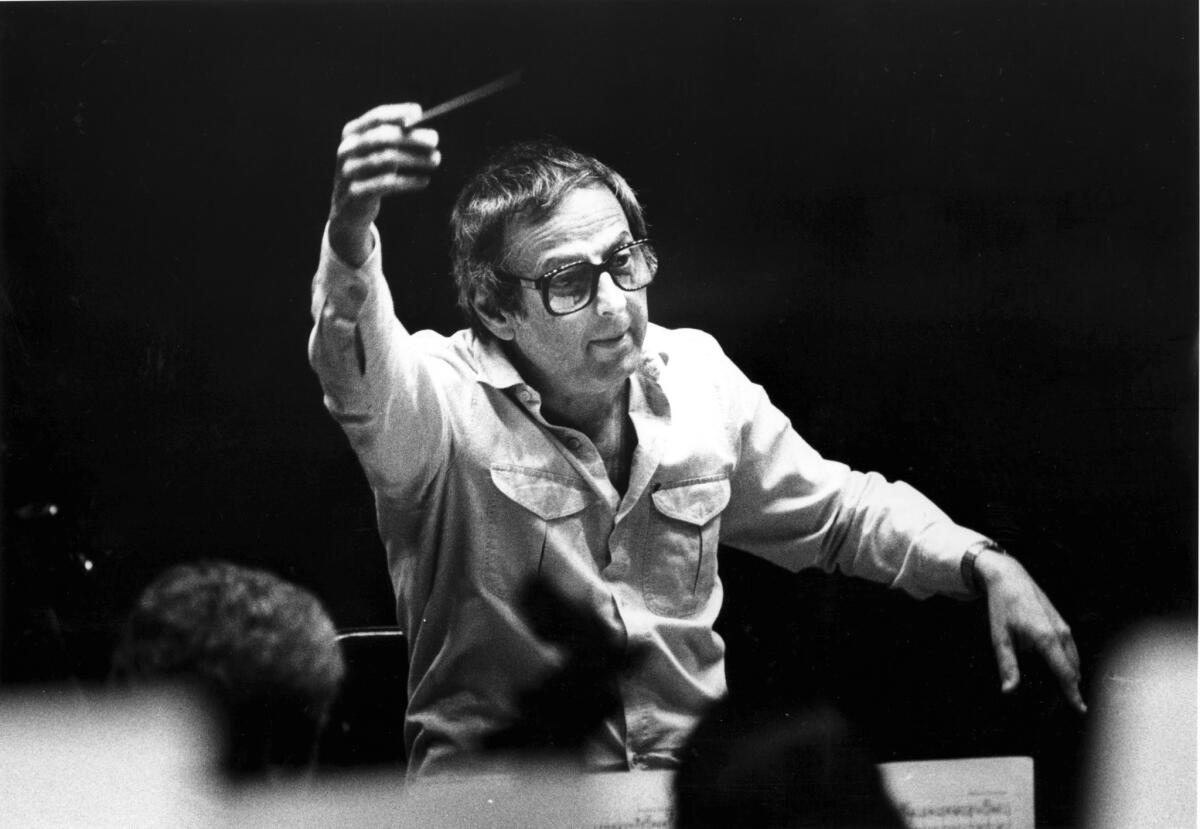

Previn conducted the world premiere in San Francisco, but these days, his conducting jobs are more limited because of the infirmities of age, which he said includes a bad case of arthritis.

Fleming said separately that she had lobbied the Metropolitan Opera in New York for years to produce “Streetcar” but to no avail.

“I think one of the problems we have in this country is an intellectual backlash against American opera and composers of anything that smells like an accessible style,” she said.

The soprano revisited the role in a new, semi-staged production that was seen at Carnegie Hall last year and then traveled to the Lyric Opera of Chicago.

The three performances of “Streetcar” at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion — it will be the semi-staged production — will provide a rare opportunity to hear Previn’s classical music in the city where he grew up.

At age 10, he and his family fled Nazi Germany and eventually settled in Hollywood. The family lived in an apartment on Sycamore Avenue just off Hollywood Boulevard, and the young Previn attended Beverly Hills High School.

Previn clearly harbors mixed feelings about the city and said he hasn’t been back to L.A. in nearly two decades. (He said it was “unlikely” that he would return to see “Streetcar” performed.)

“There is something that always struck me about L.A., and that is that they can argue all they want about putting up 16 new museums and 14 new orchestras, but it’s all about the movies,” he said. “It always is. They can’t get away from it.”

A different tune

For many years, Previn played a different tune about the movie business. As a musically gifted high school student, he landed his first studio job at 16 at MGM and happily paid his dues as an orchestrator — the person who translates the composer’s ideas into playable sheet music.

His first credited film score was for the 1949 Lassie movie “The Sun Comes Up.” He would go on to write the scores for Billy Wilder’s “Irma La Douce,” for which he won an Oscar, and other now-classics, including “Elmer Gantry,” “Designing Woman” and “Long Day’s Journey Into Night.”

He was also a prolific arranger who adapted musical theater scores for the big screen, winning Oscars for “Porgy and Bess” as well as “Gigi” and “My Fair Lady.”

His Hollywood days were filled with parties, and he socialized with many of the biggest stars of the time. In between movie jobs, he performed in chamber groups and explored new music in the Monday Evening Concerts series.

All that was a lifetime ago, Previn said. These days, his only exposure to Hollywood is through the Turner Classic Movies cable channel.

“Sometimes I hear music which is really dreadful, and it turns out to be mine. And then I hear music that I really quite like, and it turns out to be mine,” he said with a chuckle. “I found out that usually, the worse the movie is, the more music you have to write. I wrote a picture for MGM called ‘The Four Horseman of the Apocalypse’ — you’ve never seen such a load of crap in your life. And the music never stops.”

Previn left L.A. at the height of his success in 1967, though he took on occasional movie jobs in the next few years. “I was very successful and made a lot of money. And then I stepped away and said to myself, ‘Listen, you’ve had it, get out of here,’” he recalled.

Previn said he left the industry out of a desire to devote himself full time to classical music. He also experienced frustration with Hollywood.

“All of these things are really an admission of my own failures, but I didn’t think the atmosphere was conducive to doing a lot of serious work,” he said. “I found out that in order to quit that business, it wasn’t enough to leave the studio. You had to leave the city.”

Previn briefly led the Houston Symphony and had a lengthy tenure at the London Symphony. Along with Aaron Copland, he is one of the few American composer-conductors to have attained fame in both the movies and the classical world.

In 1985, he returned to Southern California to become the music director of the L.A. Philharmonic. But it was not a happy homecoming. Previn clashed with the orchestra’s imperious executive director, the late Ernest Fleischmann, who had hired the conductor.

At first, Previn declined to talk about Fleischmann in the interview, but then, without prompting, he delved into their acrimonious relationship. “There was really no subject on which we agreed. I thought he was very one-track-minded. His self-satisfaction was amazing,” Previn said.

Fleischmann’s autocratic style rankled Previn, who wanted to have a bigger voice in managerial decisions. Fleischmann thought Previn was an ineffectual music director; Previn found Fleischmann to be deceptive.

After Fleischmann hired Esa-Pekka Salonen as principal guest conductor without consulting Previn, the latter resigned in 1989.

“The next day, [Fleischmann] had the lock on my dressing room changed so that I couldn’t get in. That’s so childish.” But, Previn added, “this is all water under the bridge now. … I go for months now not thinking about him.”

Focused on composing

These days, Previn is focused on composing and he was eager to talk about the music he has written for Mutter, his fifth ex-wife, with whom he remains on good terms.

“We talk to each other I would think certainly every other day — that’s a lot. That’s more than we talked when we were married,” he said.

It was Mutter who encouraged him to display his Oscars after years of his neglecting them. “She said, ‘Listen, honey, they meant something to you when you won them. You wanted to win them, and you did win them, and there they are,’” he recalled. “She said it would be crazy for me to put them in a closet.”

Previn said he recently composed several string pieces for Mutter and is eyeing a possible one-act opera that he would write for Fleming in collaboration with playwright Tom Stoppard. The composer said he tends to write fast, a skill he picked up during his Hollywood days.

“I had to make a list of my works for my publisher recently, and I’ll be damned, I got up to over 50. That’s a lot,” he said. “I must say not all of it is good. … If I come across a piece that I don’t think works, I’ll withdraw it. I’ve done that.”

The Previn musical idiom can be described as lyrical, lush and romantic — more modern than post-modern. He eschews dissonance for the most part, and seems to abhor experimentation for the sake of experimentation.

“There’s a certain kind of new music that I don’t understand,” he confessed. “It’s my loss, but Elliott Carter — I don’t know what he wants. And [Karlheinz] Stockhausen — I have no idea what that’s about. I’d like to know, but I know I won’t, and I won’t get anything out of it.”

He praised the music of composers Toru Takemitsu and Philip Glass. He also praised some of his former Hollywood contemporaries, including John Williams, whom he said remains a friend.

“He’s a good musician, and there’s very little he doesn’t know about the orchestra. But he’s been there too long,” Previn said. “This is just my opinion. I say to him every once in a while — ‘John, get the hell out of there.’”

Looking back on his varied career — movies, conducting, classical composing — who is Previn today?

“Nowadays, if I had to fill out a blank thing that said what do you do, I would say I compose,” he said. “And conduct and play the piano. But I’m really a composer. I really like that.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.