Review: Isango Ensemble’s ‘uCarmen’ exerts overwhelming feminine power and vibrant musicality

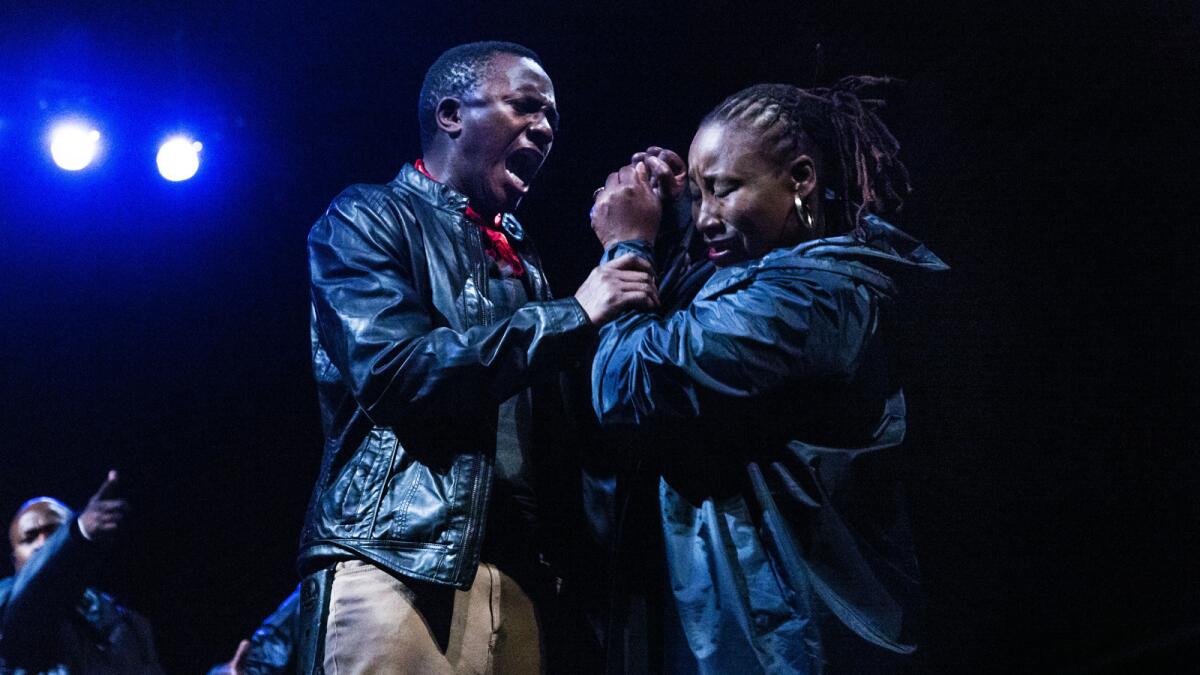

Mhlekazi Wha Wha Mosiea and Pauline Malefane in a dress rehearsal scene of “Carmen.”

- Share via

Compared with the indispensable African influence on Western visual art, music and literature for the last century, our more conventional lyric theater might seem to have been less alert. This fascinating week, however, there are three major examples of the important ways Africa and the West respond to each other on the musical stage.

My subject is Isango Ensemble’s “uCarmen,” the South African company’s unique and arresting reinterpretation of Bizet’s opera currently at the Broad Stage through Saturday. But elsewhere, UCLA Live is presenting “Desdemona” (Shakespeare’s “Othello” reflected through the lens of director Peter Sellars, Nobel Prize laureate Toni Morrison and Malian singer and songwriter Rokia Traoré), and Los Angeles Opera is mounting Missy Mazzoli’s “Song from the Uproar” (based on the extraordinary life of Swiss adventurer Isabelle Eberhardt in North Africa). All happen to be powerfully feminist in theme.

The Isango return to the Broad is very welcome. Its pervasively magic “Magic Flute” a year ago proved a revelation. As with Mozart’s opera, Isango’s “Carmen” begins with the cast milling about in costume on a bare, raked stage, flanked by a rows of marimbas.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter >>

Once the ensemble’s brilliant music director, Mandisi Dyantyis — in shirt, loose white pants and barefoot (as are all performers) — walks on, the soloists and chorus man the marimba orchestra for the overture. Throughout the opera, the singers (who are also terrific dancers), provide the instrumental accompaniment if not onstage. At times, when his orchestral resources are slight during the larger ensemble numbers, Dyantyis simply takes over, rocking out like a full one-man marimba band.

This alone provides a startling theatrical and musical vibrancy. In Mozart’s opera, Isango used this technique to explore the African roots of the mystic Masonic ritual at the heart of “The Magic Flute.” The celebratory exuberance of the performance was such that it became almost impossible to ever think about the opera without sensing its vast cultural vision.

“Carmen” is another matter. It is easy in “The Magic Flute” to overlook the darker aspects of Isango’s mission, to understand the degree to which its Mozartean exuberance relies on innovative ways to overcome hardship. “Carmen,” on the other hand, is a tragedy.

The company, formed 15 years ago by soprano and actress Pauline Malefane and director Mark Dornford-May, established itself in Cape Town with Bizet’s opera. Isango then came to international attention by turning its production into an award-winning film, “uCarmen eKhayelitsha.” In a program note, Malefane writes that she and Dornford-May have returned and reworked their “Carmen” to closely examine the problem of sexism in South Africa, where a women is raped every 17 seconds.

Isango has precedent. Given the universality of the story of a free-spirited temptress who defies male-oriented society, “Carmen” has long been one of the most readily adaptable of popular operas. The 1943 Broadway musical (and later movie) “Carmen Jones,” with an all-black cast, boldly uncovered the African experience during World War II, making Carmen a munitions’ worker and her lover, Don José, a flyboy.

In the 1980s, British director Peter Brook radically remade the opera into a highly inventive and effective chamber music-theater hybrid called “Le Tragedie de Carmen.” Around the same time, Jean-Luc Godard’s nihilistically erotic film, “First Name Carmen,” offered a whole new political perspective on seduction.

Malefane’s Carmen is not a femme fatale but a force of nature. She is a mature singer who doesn’t seduce Don José, the young soldier, so much as ensnare him by something that seems close to voodoo.

The dress is contemporary. Soldiers wear fatigues and are not to be messed with. Women wear jeans and tight tops. Don José, sung by the sweet-faced and sweet-voiced Mhlekazi “Wha Wha” Mosiea (he was a lovely Tamino in “The Magic Flute”), is the strikingly innocent exception. And it is his corruption into violence, which ultimately leads him to kill Carmen, that is the larger tragedy. The stoic Malefane seems to take her cue from Greek tragedy, sacrificing herself for the greater cause of revealing a social ill.

Musically, this is a “Carmen” all over the place. Bizet’s score does not adapt to South African musical elements as readily as Mozart’s did.

While there is traditional singing, pitches are not always tuned to a rigorous tempered scale but allow for expressive microtonality, something true of the marimbas as well.

The recitatives are the most awkward and made worse by the fact that little of the English throughout the evening could be understood (there are no projected titles of the text). Dyantyis has greatly abbreviated the opera, cutting around an hour’s worth of music, partly because of the limited resources (such as no children’s chorus) but mainly to keep the drama gripping. And ultimately, what gets the most drastically Africanized works best, especially the choruses that absorb the style of South African folk music.

That cast compels, but not always conventionally. Busisiwe Ngejane’s Micaéla, who tries to save Don José from Carmen’s clutches, does an excellent job of conveying alluring traditional femininity. Ayanda Tikolo is an Escamillo, the toreador, more oracular than virile. All — be they soldiers or smugglers, men or women — are dwarfed by Carmen. She is a symbol of resistance against sexism, but she is also such a powerful symbol of emasculation that her self-destruction may serve the opposite purpose.

Still, this is an extraordinarily thrilling ensemble of singers/dancers/marimba players like no other. Just come armed with some knowledge of the opera because you won’t understand very many words.

------------------------

‘uCarmen’

Where: The Eli and Edythe Broad Stage, 1310 11th St., Santa Monica

When: 7:30 p.m. Friday and Saturday; 2 p.m. Saturday

Cost: $50 to $100

Info: (310) 434-3200, www.thebroadstage.com

ALSO:

At the Lucerne Festival, even hip-hop skateboarders love Pierre Boulez

Pacific Opera Project’s Forest Lawn ‘Falstaff’ has an offbeat charm

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.