Review: ‘London Calling’ at the Getty and the tension between abstract and figurative painting

Is the School of London real?

A new exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum features six prominent painters working in London in the decades following World War II, and it assumes as much — although without making a vigorous case for their coherence as an artistic school one way or the other. “London Calling: Bacon, Freud, Kossoff, Andrews, Auerbach, and Kitaj” is a pretty loose-limbed show. It hinges on what the artists didn’t do rather than what they did.

What they didn’t do is make abstract paintings.

Postwar art saw abstraction definitively push figurative painting to the margins, where it mostly languished for a generation. Pushback came from several quarters in the 1950s and into the early 1960s. It rumbled through Willem de Kooning’s “Woman” paintings, as well as the black paintings of Jackson Pollock. Most notably as a group, it fueled the great Bay Area figurative paintings of David Park, Richard Diebenkorn, Elmer Bischoff and Joan Brown.

It came from London too. Elena Crippa — the Tate Britain curator who co-organized the show with Getty director Timothy Potts and drawings curator Julian Brooks — notes “the central role granted to the human figure” in the British painters’ work.

All but 12 of the show’s 51 paintings come from the Tate, which has considerable depth in these artists’ work. Each gets his own room in “London Calling.” Two-thirds of the way through, a seventh room mixes 27 small studies and works on paper by all six. The artists were friends, colleagues and carousing pals, and eventually they all showed their work with the same London gallery (Marlborough Fine Art).

Yet the artistic differences among them is most often dramatic. It’s a very long way from the strangled heads and twisted torsos of Francis Bacon to the lurching London streets of Leon Kossoff or the gooey painted flesh of a Lucian Freud nude.

Art, like life, is its own prison.

— Christopher Knight

The show’s title, “London Calling,” is somewhat incongruously drawn from the postpunk 1979 album of that name by the band the Clash. It’s incongruous because the painters were at least a generation older than the twentysomething British bandmates. But the “clash” slyly being intimated by the show is between these painters as committed figurative artists in an era dominated by abstraction.

I think that misses the mark.

That sort of clash is more fittingly applied to an art movement like the one known in Britain as Stuckism, which elevates often untutored figurative expression above the dominance of academic Conceptual art. Stuckism is reactionary. The highly refined paintings at the Getty are anything but.

Rather than oppose dominant abstraction, these artists probe the tension between the figurative and the abstract. The friction yields the paintings’ energy. Techniques of radical abstraction are used as a powerful tool in constructing a compelling image.

The show’s first great painting to navigate those shoals is Frank Auerbach’s riveting “Oxford Street Building Site I” (1959-60), which piles on thick slathers of oil paint. London was being rebuilt after the urban ruin of wartime blitzkriegs, and Auerbach positioned his painting to be as much of a physical, material construction site as the scene it depicts.

The palette is a wide array of browns — raw umber, chestnut, russet, burnt sienna and more. Red, green, black, white and other submerged colors enter the mix, but the dominant browns that Auerbach troweled on attach the gravity associated with Old Master painting to his own work. Engorged layers of firm, deliberate strokes of clotted paint are themselves objectified, even as they describe objects like machinery, a fence or a steel I-beam.

As surely as Britain was rebuilding London, Auerbach was engaged in rebuilding British painting, which had mostly languished in the Modern era. And he used abstraction as one forceful implement in his toolbox. The conjoined construction of image and canvas manufactures a painting as edifice.

The show opens with six paintings by Michael Andrews (1928-1995), the least-known, least captivating of the group. His work ranges from precisionist realism, which recalls the measured tedium in paintings by his teacher, Sir William Coldstream, to optically distorted realism, which also follows Coldstream’s dull commitment to painting only what the eye sees.

Andrews’ best work is an eccentric view of himself teaching his young daughter to swim. The child’s kicking, flailing feet dissolve into flecked splashes of light, while refraction through the dark water turns the adult’s foot into an oversize, stable anchor. A familial narrative merges with a salute to conformist tradition.

Next comes Auerbach, whose inventive fusion of abstraction and figuration packs a sudden wallop. (On first view, several landscapes could be mistaken for being completely abstract.)

Kossoff, whose thickly gestural canvases are stylistically most like Auerbach’s, chronicles the grinding anxieties of modern city life. And American expatriate R.B. Kitaj (1932-2007), who first proposed (and then withdrew) the School of London moniker, painted literary themes in overlapping, abruptly clipped planes that recall torn collages.

The two most well-known artists, Freud (1922-2011) and Bacon (1909-1992), occupy the final two rooms. Mostly they share artistic celebrity.

It’s a very long way from the strangled heads and twisted torsos of Francis Bacon...to the gooey painted flesh of a Lucian Freud nude.

— Christopher Knight

Freud (psychoanalyst Sigmund’s grandson) is among the most overrated painters of our time. Nine of the 14 canvases are in the repetitive post-1970 style that linked him to international developments in Neo-Expressionism. Impasto paint becomes sensuous skin in nudes whose eccentric poses are sometimes claimed to expose underlying states of psychological strain in the confrontational dialog between artist and model.

Yet it is the confrontational dialog between painting and viewer in his earlier work that is infinitely more captivating. The thinly painted, finely wrought 1947 picture of a staring young woman who wraps her white-knuckled hand around a kitten’s neck is as weirdly mesmerizing as anything in German New Objectivity painting from before the war. Made in its immediate aftermath, the woman’s gesture is somewhere between caressing and strangling innocence and autonomy. A chill goes up your spine.

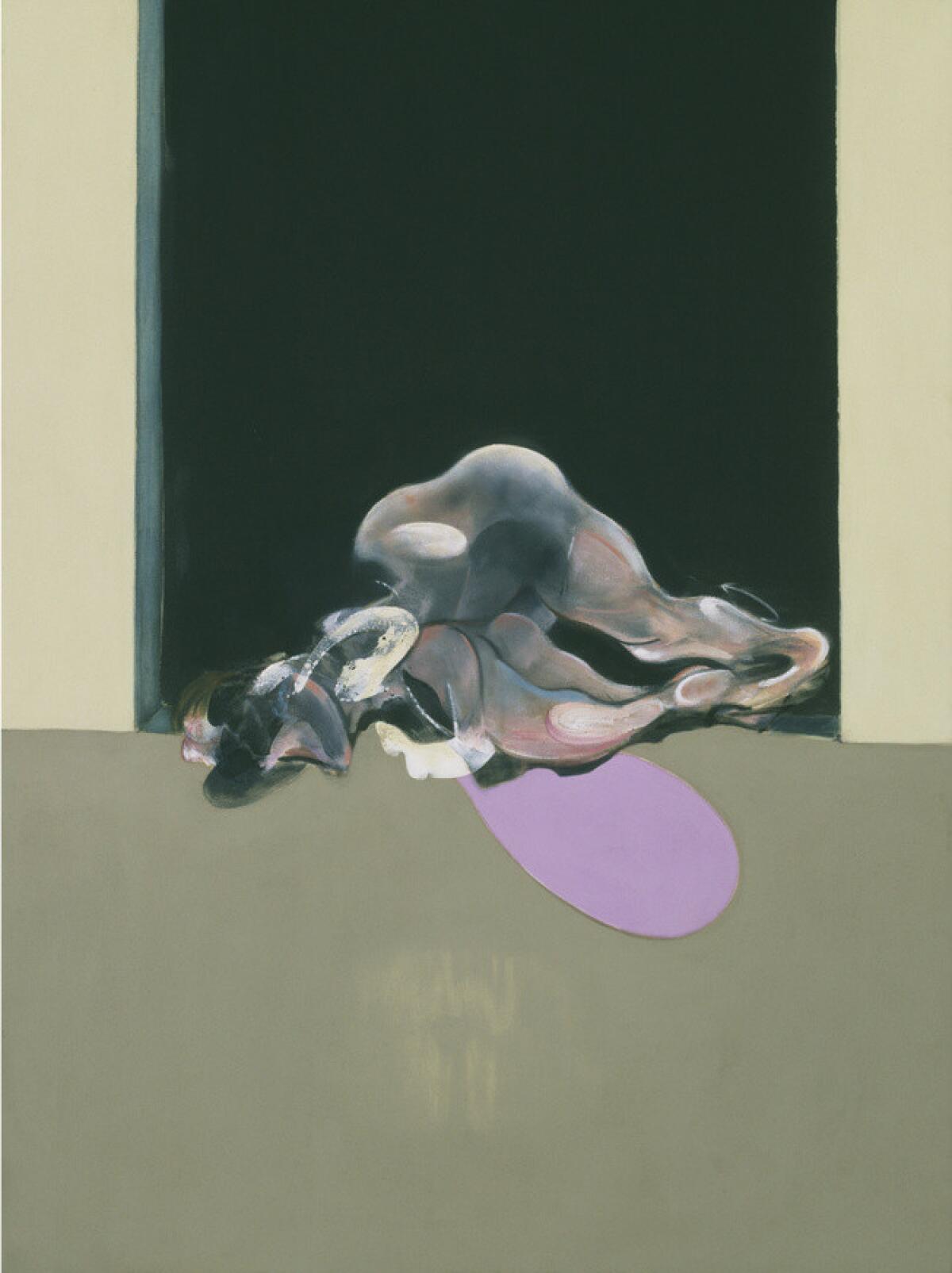

Bacon’s seven paintings are capped by a big triptych of disquieting figures trapped within flat, blank, geometric voids and caged in a wide, golden frame — a Bacon signature. Art, like life, is its own prison, yet also a place for transgression.

A seated self-portrait on the right is loosely mirrored in a seated portrait at the left showing his lover, George Dyer, who had committed suicide barely 10 months before. In the triptych’s center, the spot where a traditional religious painting would put the Virgin Mary or a crucified Christ, a blob of two entwined figures grapples in a macabre dance of sex and death. Before 1969, homosexual coupling was criminal under British law.

The slick, carefully contrived elegance of Bacon’s paint handling is regularly interrupted by oozing discharges of color. There is no narrative here, only direct visual sensation connected to visceral experience.

“London Calling” is unusual — even unprecedented — for the Getty. It’s the museum’s first-ever historical survey in the field of 20th century painting. The Getty’s own European painting collection ends circa 1900, and the conceit is that contemporary British figurative painting is being connected to a collection of pre-Modern European painting. That’s pretty wobbly.

I’m not so sure we really need yet another art museum to present overviews of contemporary art, especially one with the Getty’s distinctive capacity to explore just about anything else. But if it is to be, perhaps connections of more depth can be drawn.

Bacon’s paintings, for instance, were profoundly influenced by camera images — photojournalism, film stills from Sergei Eisenstein’s “Battleship Potemkin,” medical albums, Eadweard Muybridge’s animal locomotion studies (the center panel in the show’s triptych comes from the British-born California photographer’s studies of wrestlers) and more. The Getty, given its unparalleled photography collections, is uniquely positioned to examine such an angle.

-----------------------------------------------------

‘London Calling: Bacon, Freud, Kossoff, Andrews, Auerback and Kitaj’

Where: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Brentwood.

When: Tuesdays through Sundays, through Nov. 13. Closed Mondays.

Admission: Free. (Parking $10-$15.)

Info: (310) 440-7360, www.getty.edu

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.