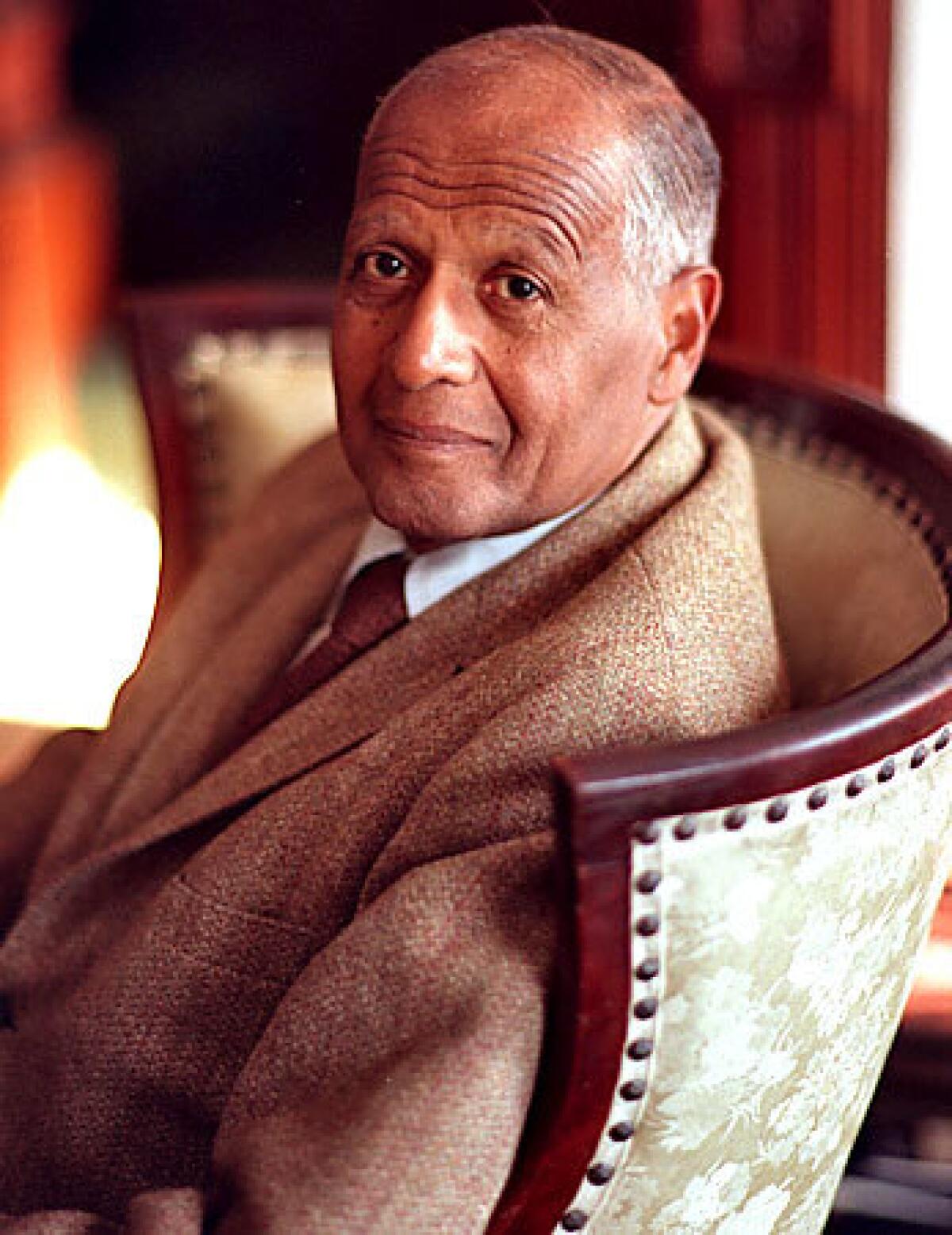

Roy DeCarava dies at 89; art photographer depicted the African American experience

- Share via

Roy DeCarava, an art photographer whose pictures of everyday life in Harlem helped clarify the African American experience for a wider audience, has died. He was 89.

He died Tuesday in New York City, his daughter Wendy DeCarava said. The cause was not given.

DeCarava (pronounced Dee-cuh-RAH-vah) photographed Harlem during the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s with an insider’s view of the subway stations, restaurants, apartments and especially the people who lived in the predominantly African American neighborhood.

FOR THE RECORD:

Roy DeCarava obituary: The obituary of art photographer Roy DeCarava in Thursday’s Section A misstated the first name of Peter Galassi, a curator at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art, as Jonathan. —

He also was well known for his candid shots of jazz musicians -- many of them taken in smoky clubs using only available light. Shadow and darkness became hallmarks of DeCarava’s style.

“Roy was one of the all-time great photographers,” Arthur Ollman, founding director of the Museum of Photographic Arts in San Diego, said in 2005. “His photographs provided a vision of African American life that members of the white fine art photography establishment could not have accessed on their own.”

DeCarava’s first major exhibit was at the Museum of Photographic Arts in San Diego in 1986. Ten years later, he was the subject of a one-man exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

“What’s extraordinary about the pictures is the way they capture his lyrical sense of life,” Jonathan Galassi, a curator at the Museum of Modern Art, said in a 1996 interview with ABC.

“You see pain, you see anger and you see an extraordinary quality of tenderness,” Galassi said in a separate interview with CBS.

Using a small, 35-millimeter camera that allowed him freedom to roam, DeCarava captured spontaneous moments. He shot in black and white, creating highly impressionistic images, and printed in a style that produced velvety shades of gray and black.

Some of his earliest photos show young couples dancing in their kitchen on a Saturday night, and a father and his children dressed in their Sunday best, watching the Harlem River go by. He photographed men talking together in a basement that doubled as their clubhouse.

DeCarava told National Public Radio in a 1996 interview that when he started taking pictures “there were no black images of dignity, no images of beautiful black people. There was this big hole. I tried to fill it.”

He did not ignore the problems of the black community, but usually addressed them in subtle ways. One of his best known photographs shows a young woman in a long white gown and a corsage who stands in rubble outside a tenement house. She is in sunlight, facing shadows. The image raises obvious questions about her future.

As a young photographer, DeCarava saw his share of overt racism, said Ollman, who interviewed him at length for the 1986 exhibit in San Diego. The social upheavals of the 1960s improved the situation.

“Photo editors came along who could relate to editorial dissidence,” Ollman said. DeCarava’s uncommon subject matter became more accepted, but he still experienced racism of a different sort.

“Roy was sometimes referred to as a black photographer, a qualifier that can be a subtle attempt to marginalize someone,” Ollman said.

If there were few images of beautiful black people before DeCarava made them, there were also few black photographers who had achieved wide recognition.

Gordon Parks, seven years older than DeCarava, broke the color line in photojournalism in the 1940s, shooting for Life, Look and other national magazines. James VanDerZee became known beyond the black community for his portraits of middle-class African Americans that offer glimpses into Harlem in the 1920s and ‘30s. But DeCarava’s interest in photography as art led him in another direction.

Soon after DeCarava started taking photographs in the late 1940s, he found a powerful mentor in Edward Steichen, director of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, who encouraged DeCarava to apply for a Guggenheim fellowship.

DeCarava was the first black photographer to receive the grant, in 1952. He used the $3,200 to support himself during his first year of photographing in Harlem.

The images he took that year became a book, “The Sweet Flypaper of Life” (1955), with text by Langston Hughes, the foremost black poet of his time.

The book captures images of a community busy at the art of living: A black matriarch wearing her good hat pauses on the street to give DeCarava a warm, confident smile. A man in a plaid flannel shirt sits at his kitchen table holding his baby boy. Other shots show poverty and isolation. A young teenage boy alone in a junkyard is shown in DeCarava’s honest but gentle terms.

Steichen included DeCarava’s photograph of a young couple dancing and another of a woman jazz musician playing bass in “The Family of Man,” a successful exhibit that featured images of ordinary people from around the world and toured countries for eight years after it opened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1955.

DeCarava began working on a second book, “The Sound I Saw, Improvisation on a Jazz Theme,” in 1964. A serious jazz fan who kept his own saxophone outside the door of his darkroom at home, DeCarava had a passion for the big band and bebop eras.

He created “The Sound I Saw” from images he shot in clubs, recording studios and the private homes of the biggest names in jazz in the 1940s, ‘50s and early ‘60s.

“Nobody since Roy has yet photographed the jazz scene with the same intimacy,” Ollman said. “No one’s done it better.”

Among the better known images, Billie Holliday relaxes beside a piano in a friend’s living room. Miles Davis stands on a small stage, stooped over his trumpet like a man in a private conversation. Duke Ellington, dressed in white tie, smiles at the camera while he is on a break in a recording studio.

DeCarava’s unobtrusive style of working and his love for rich, dark tones made him an easy fit with the late-night jazz scene.

Art photography remained his passion, but DeCarava supported himself as a freelance photojournalist.

Starting in the late 1950s, he shot for Look, Newsweek, Life and as a contract photographer for Sports Illustrated from 1968 to 1975. He photographed artists, musicians and sports stars.

His experience as a photojournalist left a bitter taste, he later said. It led him to serve as chairman of the American Society of Magazine Photographers’ Committee to End Discrimination Against Black Photographers from 1963 to 1966.

“When I was trying to sell my photographs, I would take them to art directors and they were literally shaking when they saw my work,” DeCarava said in an interview with “CBS Sunday Morning” in 1996. His work and self-confidence stirred fear, disbelief, even anger. “They were not used to seeing black artists walk through the door with a portfolio of photographs.”

Born Dec. 9, 1919, in Harlem in New York City, DeCarava was the only child of a Jamaican mother and an American-born father who separated when he was a child.

After graduating from high school in 1938, he worked as a sign painter for the Works Progress Administration, the federally funded program for artists during the Depression.

He attended Cooper Union, the Harlem Art Center and George Washington Carver Art School, studying architecture, sculpture, painting, printmaking and drawing.

After serving briefly in the Army as a topographical draftsman, he worked as a commercial artist and had his first exhibit of silk-screen prints at a New York gallery in 1947.

At first, he used a camera as his notebook for recording street scenes he wanted to paint. But the camera’s particular advantages won him over. He had his first photo exhibit in 1950 at the Forty-Fourth Street Gallery in New York City.

He opened his own exhibit space, the Photographer’s Gallery, in his apartment in 1955 and showed work by photographers Berenice Abbott, Harry Callahan and Minor White, along with his own. After two years of strong reviews but slow sales, DeCarava closed the gallery.

Nine years later, he became founding director of the Kamoinge Workshop (the term means “group effort” in Kikuyu, the Bantu language of Kenya). The program supplied a sense of community and an exhibit space for younger black photographers. Anthony Barboza, Adger Cowans and Louis Draper were among the group’s first members.

During the public demonstrations of the 1960s, DeCarava photographed the small incidents and personal interactions that caught his attention. He moved into the crowd at the March on Washington in 1963 and at a fair housing demonstration in Brooklyn, N.Y., that same year.

One shot, “Force, Downstate” (1963), from the Brooklyn protest, shows a woman’s legs and feet upside down. Her ankles are grasped by different pairs of hands as she is carted off by police in a nonviolent confrontation.

“The vivid social impact of his pictures is integral to the elegant formal composition he remarkably establishes in the frame,” Los Angeles Times art critic Christopher Knight wrote in a 1996 review of a retrospective exhibit.

DeCarava was well established as a leading photographer when the Metropolitan Museum of Art planned the 1969 exhibition “Harlem on My Mind.” The show turned contentious when museum administrators failed to include Harlem’s civic leaders and artists from the planning stages onward. DeCarava was invited to be part of the exhibit, but instead he joined the protesters who picketed it.

He moved from journalism to teaching in the late 1960s, first at the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in New York, and at Hunter College starting in 1975.

He married art historian Sherry Turner in 1970. She survives him, along with their three daughters, Laura, Susan and Wendy; as well as a son, Vincent, from a previous marriage.

Photojournalism was a side-step in his career, DeCarava believed, but it broadened his subject matter and attracted a wider audience.

“Whatever’s there, I use it,” DeCarava said of his work in a 1996 interview with National Public Radio. “I improvise. Improvisation is all about individual interpretations, individual expression. And that’s what I’m doing.”

Rourke is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.