How the dense grids of artist Charles Gaines took the ego out of art

When Charles Gaines was in elementary school in Newark, N.J., one of his teachers noticed that this son of a construction worker and seamstress was skilled at drawing.

“My teacher told my mom that she should encourage me to go into art because I could be the ‘first black artist,’ “ Gaines remembers with a chuckle. “Of course, there was already a rich black history in art, but nobody knew it because it wasn’t taught.”

He went on to attend an arts high school in Newark and pursue art as a career. But at first, art was hardly his passion.

“I look at myself in those days as being unconscious,” says the artist, whose early work is the subject of a major exhibition now on view at the Hammer Museum. “You opened a door, and I walked through it.”

Only during his third year at Jersey City State College (now New Jersey City University), a time he describes as “the awakening,” did he decide that making art was something he had to do. Even so, it took him time to find his voice.

“I was doing these really terrible paintings,” he recalls of his work from the early 1970s. “It was a pastiche of hard edge, expressionism and figuration.”

One of the most time-honored clichés about art making is that the artist’s studio is a place of emotional ritual: where the solitary genius engages in contemplation, then takes action, spilling his innermost guts all over a canvas.

Gaines likens that ritual to a dance — between chair and canvas and canvas and chair — one that’s supposed to be filled with struggle, emotion and joy. Except he felt none of those things as a young artist when he sat before a blank canvas.

“It felt foreign,” he says in his typical soft-spoken manner. “I was having problems feeling connected to the idea of the expressive gesture, that anything that motivated a mark on a canvas would come from something within me.”

Gaines wanted another way of making images, one that took the ego out of painting. One place he found that inspiration was Tantric Buddhist art. He saw the grid-like drawings and mandalas as maps of impulses and energies in the cosmos.

“These drawings are not a function of the expression of the monks that produced them,” he explains. “They are a manifestation of a Zen-like practice.”

That discovery put Gaines on a new path as an artist. He turned away from the abstract and figurative painting he had long struggled with and began to create dense grids populated with numbers and colors. He used these to map mathematical equations, the shape of walnut trees and the ephemeral movements of a choreographer friend. In the process, he created pixelated forms that often read like shadows. The underlying idea was that there is always some outside force shaping what appears on the page.

“I had been looking for something that was a systematic way of realizing a form,” he says. “In Western society, the grid is it.”

These works have served as the foundation to the artist’s long-running career, which explores notions of layering and mapping, of merging ideas in methodical, even rote, ways. Gaines’ work has been featured in museum exhibitions from New York to Stuttgart, Germany. He has been the recipient of a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship. For years, he was represented by the legendary New York gallerist Leo Castelli. He is also a highly influential professor at California Institute of the Arts.

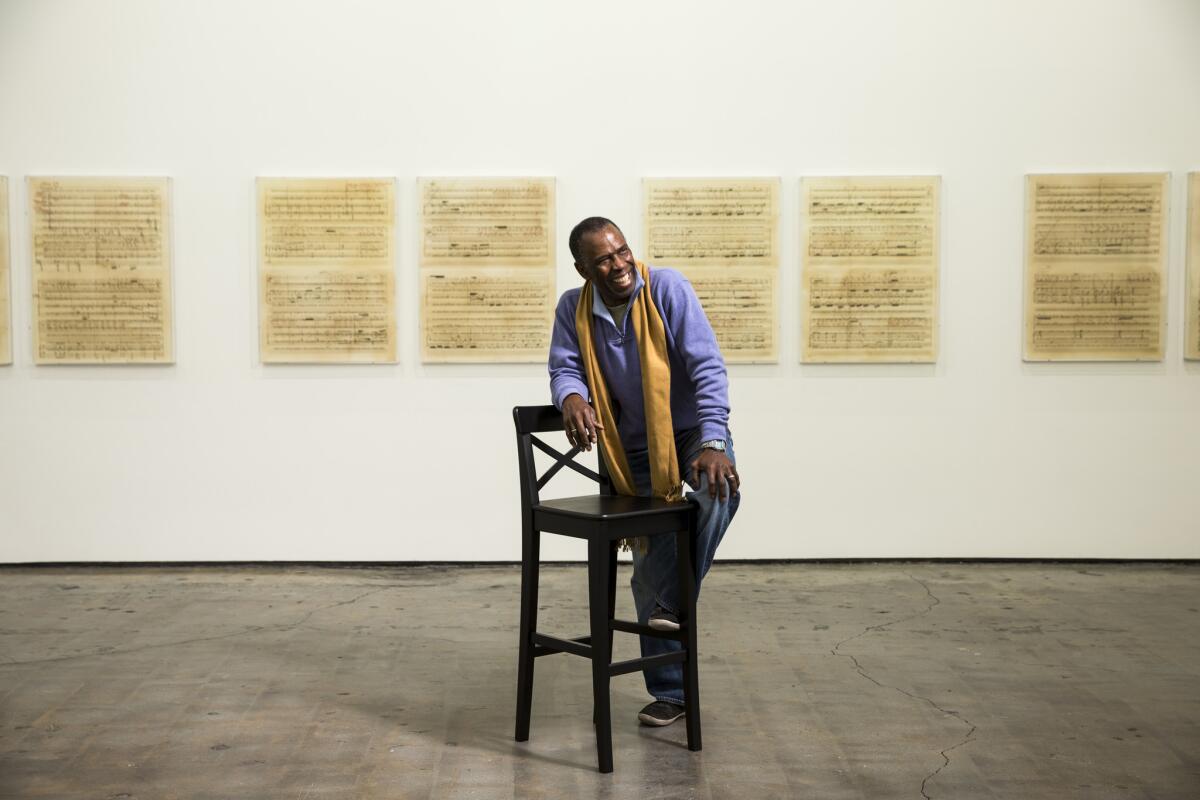

The Hammer Museum show, “Charles Gaines: Gridwork: 1975-1989” (first organized by the Studio Museum in Harlem) brings together many of the artist’s gridded pieces, from early black-and-white geometric shapes inspired by math, to more colorful, figurative works that include photography and paint. (He also has a concurrent show of new work at Art + Practice in Leimert Park, organized by the Hammer.)

For years, Gaines’ grids existed below the institutional radar. When he first debuted them in the 1970s, they drew the praise of key conceptual artists (Sol LeWitt was a fan) and were shown in important galleries (such as Castelli), but there was little critical or curatorial attention. When Gaines was selected to participate in the 1975 Whitney Biennial, the curators chose to include one of his older abstraction paintings.

“There was a period of 15 years or so when I couldn’t give that work away,” recalls the artist, now 70, as he surveys his freshly installed pieces at Art + Practice.

When he made his early grid pieces, he was teaching at Cal State Fresno — far from the heart of the New York art world. Moreover, he hit the scene as a conceptual artist, just before the art world began to turn its attention back to painting. And he was a black artist who wasn’t making work that identified him as such.

“I wasn’t getting attention from the mainstream art world or the black art world,” he says, “for peculiarly different reasons.”

Certainly, when it comes to art, Gaines has walked a unique path. After completing his master’s at the Rochester (N.Y.) Institute of Technology, he landed a teaching gig at Mississippi Valley State College, a historically black college in Itta Bena, Miss.

“I was not unfamiliar with the South,” he says. “I grew up going to Charleston” in South Carolina. “Charleston was no walk in the park, but Mississippi was something else entirely. They were still lynching people when I was there.”

But it was also the 1960s. A witness to civil rights marches and the upheaval caused by the death of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Gaines saw student protests quelled by police employing military-style tactics. Anxious about the mood on campus, he quit his job without having another lined up — even though that made it him eligible for the draft.

“I was going to escape Mississippi by going to Vietnam,” he says with a wry laugh.

Instead, he quickly landed the job at Cal State Fresno — which had a forward-thinking arts department that brought in important conceptual thinkers as visiting scholars. Those connections — with John Baldessari, Michael Asher, Adrian Piper and others — helped keep Gaines linked to the larger art world.

And Fresno is where he arrived at the grid. His “Regression Series,” made between 1973 and 1974, began with an equation he plotted as a series of numbers on graph paper. This resulted in a mound-like form. That shape’s numbers were used to create another mapped equation and another bulbous mound. Other equations led to diamond and ovoid patterns.

Making the pieces was laborious.

“There’s nothing interesting about doing them,” he says. “The enjoyment comes in discovering something I couldn’t imagine.”

The grid works — like all of Gaines’ work — are more rooted in philosophy than in the creation of some aesthetic experience. Even so, they can be a wonder to look at. His show at the Hammer contains images of trees atomized into a “Matrix”-like stream of colors and numbers, as if the image was being stripped down to its programming code.

For Naima Keith, the curator who organized the Harlem show, reuniting these little-seen early works in a museum show fills a gap in the record of 1970s conceptual art.

“There simply hadn’t been a retrospective or a focus on the early work,” she says. “Just because someone is recognized as an important artist doesn’t mean that they’ve necessarily received their due in museums.”

Putting together the show was definitely a labor of love for Keith, who says it was the first exhibition she pitched when she landed at the Studio Museum in 2011.

“A lot of it,” she says, “was looking through old catalogs and talking to Charles or his ex-wife. And she’d say, ‘Oh, Charles gave one of the trees to a neighbor.’ ... It was more than a year of trying to track down as much as we could.”

For Gaines, who has lived in Los Angeles since the late 1980s, when he began teaching at CalArts, the exhibitions at the Hammer and at Art + Practice, represent a delicious moment of recognition in his hometown. They also mark a curious personal journey: Art + Practice was founded by a former student, the collagist and painter Mark Bradford.

“I’ve been watching Mark’s career from a distance for many years,” says Gaines. “We’ve stayed in touch. Every time he takes a leap, it’s personally gratifying. When he won the MacArthur grant, I was brought to tears.”

But, above all, Gaines is glad that his early work is getting a little bit of due.

“How can work be completely ignored in one moment and accepted in the next?” he asks rhetorically. “I don’t think it’s that you are ahead of yourself. It’s the gatekeepers that change.”

“Charles Gaines: Gridwork: 1975-1989” is on view at the Hammer Museum through May 24. 10899 Wilshire Blvd., Westwood, Los Angeles, hammer.ucla.edu. “Charles Gaines: Librettos — Manuel de Falla / Stokely Carmichael” is on view at Art + Practice through May 31. 4339 Leimert Blvd., Leimert Park, Los Angeles, hammer.ucla.edu.

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.