Q&A: Graciela Iturbide talks about going viral, L.A. cholos and shooting Frida Kahlo’s bathroom

- Share via

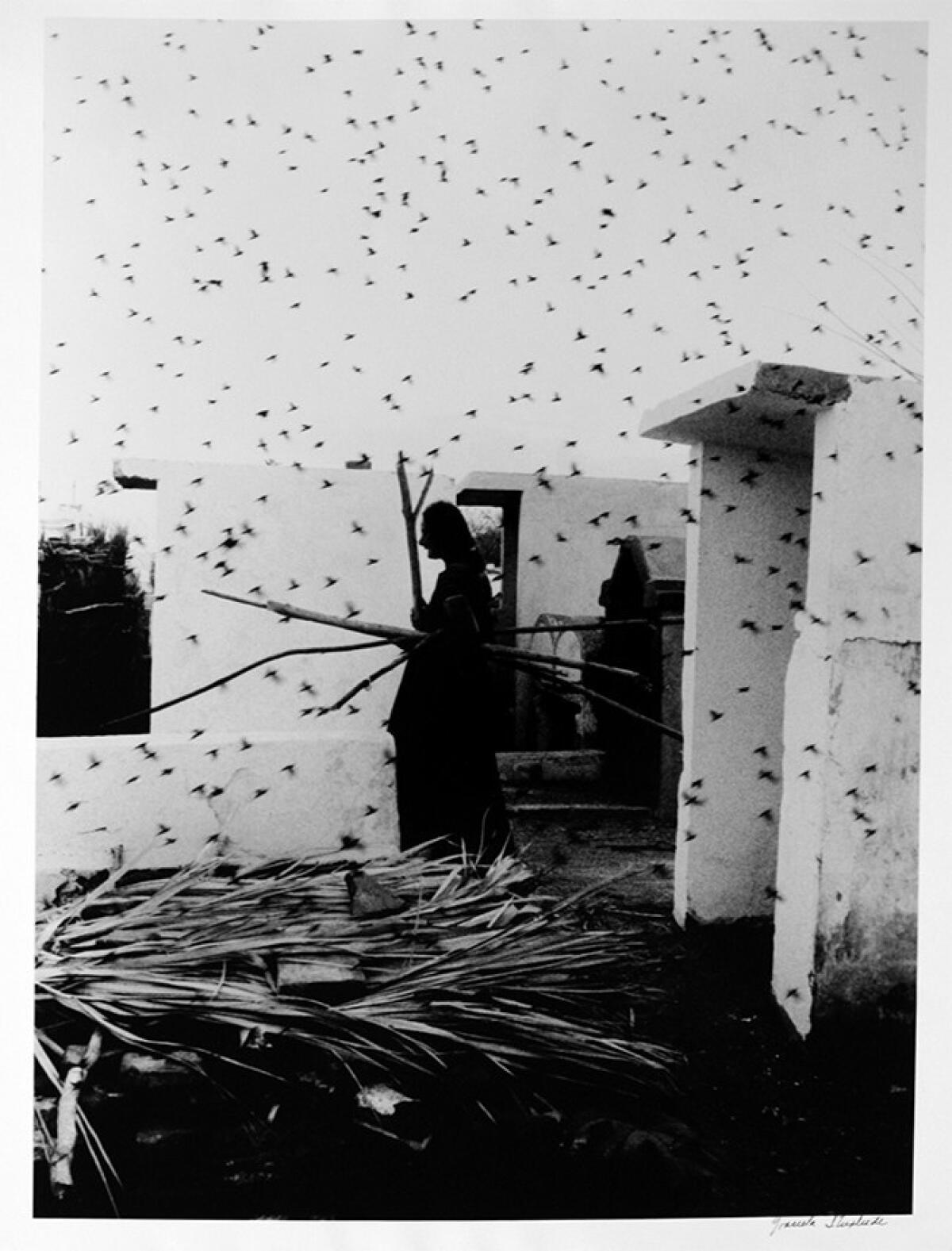

Countless photographers hope to produce a single indelible image over the course of their careers, something so unforgettable it is seared onto the collective unconscious. Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide has made not one but several of these images.

There’s the photograph of a Zapotec woman in a southern Mexican market, her head draped in a crown of iguanas striking a pose. There is the spectral figure of an indigenous Seri woman, clad in a long dress, who floats through the desert clutching only a boom box. And there is the woman, with the seen-it-all stare, having a drink and a smoke in a Mexico City bar — her mortality, and ours, writ large in a mural of a skull that looms large over her shoulder.

There are others who are recognizable too: The Zapotec transgender woman framing her striking features with a mirror. A mask-wearing reveler standing in the middle of a dry field, the party over, out of time.

Iturbide’s images are part of museum collections all over the world, including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in the Bay Area and the Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

They are bishops and archbishops and you can imagine what I am to them: the crazy one who studies film and gets divorced.

— Graciela Iturbide, photographer, on her family's reaction

But at 75, Iturbide shows no signs of slowing down. The Mexico City-based photographer recently published the book “Avándaro,” which gathers some of her earliest images — from a 1971 rock festival in Mexico. And she has spent time photographing communities of refugees in Mexico and Colombia, many displaced by drug and other violence, as part of a project sponsored by the UN Refugee Agency. (These were shown at the Annenberg Space for Photography in Century City last year.)

“That project was really hard,” says the diminutive Iturbide, sitting in a cloud of cigarette smoke in a second-story alcove in her Mexico City home. “It was like touching the misery of man. It was very intense for me.”

This fall, Iturbide and her work will be highly visible around Southern California when the Pacific Standard Time: Los Angeles/Latin America series of exhibitions kick off in the fall.

Her photography will appear in two separate shows for PST: LA/LA, as the series is known.

The Hammer Museum will include her work in “Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1965-1980.” This will consist of now-historic images she took in the southern Mexican village of Juchitán in the 1970s and ’80s chronicling life in the matriarchal indigenous settlement. It’s a series that to this day remains her favorite, she says, “because of the closeness I have with the people of Juchitán.”

The Ruth Chandler Williamson Gallery at Scripps College will present numerous works from throughout Iturbide’s career as part of the three-woman show “Revolution & Ritual” which will also include photography by Sara Castrejón and Tatiana Parcero.

Iturbide will also work with artist James hd Brown, the founder of Oaxaca’s Carpe Diem Press, to create a special book of her work tied to the PST: LA/LA show “James hd Brown: Life and Work in Mexico” at USC’s Fisher Museum.

And since all of that isn’t quite enough, she will also be the subject of “Photographic: The Life of Graciela Iturbide,” a new graphic biography by Isabel Quintero and Zeke Peña to be released by Getty Publications in September.

Since the dawn of her career, Iturbide has had a knack for capturing the many layers of Mexican identity — the indigenous draped in the Catholic and the modern. The artist, writes critic Marta Dahó in the Scripps exhibition catalog, is part of a generation of photographers who realized the “complex task of visualizing the survival of [indigenous] cultural beliefs.”

Iturbide is gracious and funny, inhabiting a cozy house in the Mexico City district of Coyoacán that is stuffed to the gills with books and artifacts accumulated over a lifetime travel. Following at her heels is a French bulldog named Horr, short for “Horrible.”

In this edited conversation, she discusses some of the high points of her career, why she was compelled to do a series on the cholos of L.A.’s Eastside, and how a youthful stint in a nunnery shaped all the imagery she has produced since.

In 1979, you snapped an image of a Zapotec iguana vendor in Juchitán. That picture of Sobeida Díaz, known as “Our Lady of the Iguanas,” is now iconic, reproduced in paintings, drawings and even tattoos. What’s it like to have something go viral?

It’s very strange, no? That image is no longer mine. In Juchitán there is now a sculpture of her based on that photo. It has appeared as graffiti. There are murals. In Juchitán, she is like a saint. “Our Lady of the Iguanas” is part of daily life. I’m now making a tomb for her. She passed away. I was in Juchitán recently and somebody said, “How is it possible? She is so famous, and look at her tomb.” So I hired an architect to make a tomb for her. And Francisco Toledo, the painter, he is going to create some iguanas to place on there. I imagine it will turn into a kind of shrine. Everybody adores her.

You travel throughout Mexico for your work. How have you seen the country — and communities such as Juchitán — evolve over your career?

Horrible, horrible. I won’t go to certain communities because of the narco. For example, in Juchitán all the women used to wear their gold jewelry. Now they wear only costume jewelry because people will yank it. I was there recently with some young people who invited me, so I felt protected, but I could still see what was going on around. But that thing that I used to do, where I would go live with a community for a time and photograph them — it’s too dangerous now because of the narco.

Juchitán has historically been a Zapotec matriarchal society. Have these traditions withered away in the face of the narco presence?

The traditions continue. The women are the ones who manage the economy. They are the ones who operate the market. Men cannot enter the market — only muxes, who are gay men, and they work with the women. It’s very accepted. They call them muxes in the Zapotec language. And they continue the traditions: the weddings, the quinceañeras, etc. — except now they can’t wear their gold.

About a decade ago, you photographed a bathroom in painter Frida Kahlo’s Mexico City house that had remained shuttered for 50 years upon the orders of Diego Rivera. What was that experience like?

Very intense. The bathroom had been shuttered on Diego’s order, surely because it contained all of her things. And, indeed, there were letters and other personal objects. It was very interesting. Like entering a prohibited space, frozen in time — with some terrible smells. Imagine a bathroom that’s been closed off for 50 years.

I wasn’t a Frida-maniac, nor am I now a Frida-maniac. Nowadays she is practically “Saint Frida.” But there I learned that she was a marvelous woman who contended with a lot of pain. I have an image of the Demerol — the morphine she used to take. She had a lot of pain. But she kept painting. Painting was her therapy. I feel like I got to know her better.

You did a series on Los Angeles in the 1980s, documenting a group of cholos who lived on the Eastside of Los Angeles. What intrigued you about them?

I was interested in cholos because they are of Mexican origin. I was interested in the ways in which they had been marginalized. I lived there and photographed them. Many had been in jail, then they’d get out of jail and back into gangs. There was White Fence. There was Maravilla. They would get together in the park at night to do drugs and everyone would respect each other in a kind of cold war. But it was still very dangerous. You’d be taking a picture and then you’d hear [makes the sound of a gun being cocked]. It was very heavy.

For me it was very interesting because they have a nostalgia about Mexico that isn’t always based in fact. A group of them told me, “We want you to photograph us by the mural of the mariachis.” And it was a mural of Mexico’s historical heroes: [19th century President] Benito Juarez, [the revolutionary] Pancho Villa. They can be really mistaken about Mexico, but they still have a profound nostalgia for it.

I was also very interested in the influence the cholos had. Afterwards, I went to photograph cholos in Tijuana. The cholos there would be looking at magazines that showed cholos in East L.A., so it was interesting to see the paths it took.

What are you photographing now?

I’m occupied by things like rocks — rocks, water, air. These elemental things. But I never know, because something else may arise out of it. I also continue to work a lot in botanical gardens, especially gardens in which the plants are healing from some sort of injury.

What interests you about injured plants?

I don’t know. Because I’m morbid? [Laughs.] I like to see them with bandages and IVs, gardens that are undergoing some sort of therapy. When the garden has healed, they always want me to photograph it. But I say, “No, that isn’t my garden!”

You began by studying cinema. How did you end up a photographer?

I wanted to study art, philosophy and letters, but my family was very conservative. They said, “How? No!” But I heard that there was a film school and I just went and enrolled. I had no idea what I wanted to do — whether I’d be a scriptwriter or a cinematographer. But there I had the good fortune to meet [the key Modernist photographer] Manuel Alvarez Bravo, who taught there, and I became his assistant.

What was your family’s reaction when you took off to study film?

I was the eldest of 13. I got married very young — at 19 — and then I got divorced. I come from a very conservative family. They are bishops and archbishops and you can imagine what I am to them: the crazy one who studies film and gets divorced. Now they accept me, but in the beginning my parents, what can I tell you, we didn’t really speak.

But I was very happy. I got divorced and I was very happy. [Laughs.] My children are my accomplices. I have two: Manuel [Rocha Iturbide], who is a composer, and Mauricio [Rocha Iturbide], who is an architect.

How did those experiences of your youth shape your work?

In a lot of my work, you see the paraphernalia of the Catholic Church: angels, crosses, all of the things I lived as a girl. I was sent to study at a convent of the nuns of the Sacred Heart. I had boyfriends, so my parents sent me far away. The school was in San Luis Potosí. My parents would visit me from Mexico City. I was there for three years — as a novice. I had to live there and you couldn’t speak. I’m an atheist now, but those influences are still there.

They had a huge library. I learned a lot about Spain’s Siglo de Oro [a literary Renaissance during the 16th and 17th centuries]. That was in high school. I left and then I studied for about a year. Then I got married — and then, later, divorced from the father of my children.

Photography was my salvation.

Is it still?

Yes! Yes, it is.

“Revolution & Ritual: The Photographs of Sara Castrejón, Graciela Iturbide and Tatiana Parcero”

Where: Ruth Chandler Williamson Gallery, Scripps College, 251 E. 11ths St., Claremont

When: Opens Aug. 26 and runs through Jan. 7

Info: rcwg.scrippscollege.edu

“Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1965-1980”

Where: Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd., Westwood, Los Angeles

When: Opens Sept. 15 and runs through Dec. 31

Info: hammer.ucla.edu

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.