Could $499,000 in grants that help our soldiers be one reason Congress spared the NEA?

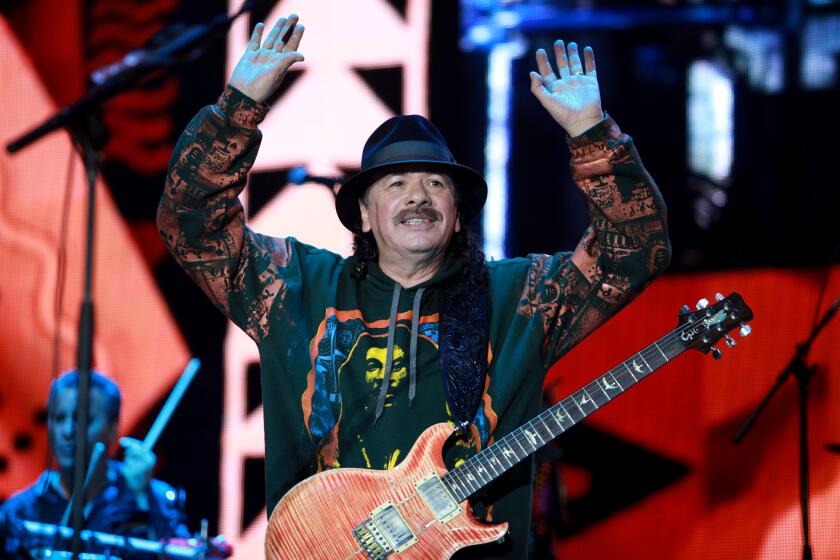

“Wait a minute, Shakespeare’s funny!” U.S. Army veteran Ariel Bell talks about how she discovered the Shakespeare Center of LA. From Carolina A. Miranda’s story ”Could $499,000 in grants that help our soldiers be one reason Congress spared the NEA?”

- Share via

The National Endowment for the Arts is breathing a sigh of relief this week. After

There’s the theater program geared to military families in North Carolina, art-making classes for veterans in Salt Lake City and Shakespeare productions staffed by veterans in Los Angeles — not to mention a beloved children’s theater program based in Missoula, Mont., that organizes productions at far-flung U.S. military installations around the world. These are just a few of the programs the NEA has helped fund.

In fiscal year 2016 alone, the NEA made 25 grants totaling $499,000 to support cultural projects that in some way involve veterans or active military. For comparison, an estimated $627,000 through 32 grants was given to programs geared to individuals with disabilities and another roughly $202,000 through 15 grants was given to programs for seniors. These are small amounts when compared with the $124 million that the NEA gave out in fiscal year 2016 — through nearly 2,500 awards, including direct grants, partnerships and individual awards. But they are not without an important effect.

At the Cape Fear Regional Theatre in Fayetteville, N.C., which lies adjacent to the U.S. Army base of Fort Bragg, a $15,000 grant from the NEA in 2016 helped the theater fund the creation of “Downrange: Voices From the Homefront” by Mike Wiley, a play that examined the struggles faced by military families.

In Salt Lake City, a $10,000 NEA grant for the community arts group Art Access in 2015 helped that organization fund art-making classes and a playwriting workshop for veterans led by a nationally recognized playwright.

And in Southern California, the Shakespeare Center of Los Angeles this year received a $10,000 grant for a pop-culture-inflected version of “Macbeth” that will employ military veterans as paid crew.

Despite the last-minute reprieve for 2017’s NEA budget, many government observers say that the agency is not out of the woods for next year’s budget. Long before the election of Donald Trump, small-government conservatives have sought to cut back the NEA, describing it as “welfare for artists.” In 1981, Ronald Reagan attempted to dismantle the NEA. In the years since, the agency has endured regular threats of de-funding from Congress over how the agency makes grants and who gets its money. If the NEA were to be slashed, organizations such as the Shakespeare Center would either have to seek funding elsewhere, cut back their offerings or, in some cases, simply shut down.

We had students in class who could not get through their script without weeping as they were reading it out loud. There was some catharsis there.

— George Sumner, Army veteran

That, says Ariel Bell, an Army veteran who served in Bosnia and works on productions for the Shakespeare Center, would create a vacuum for veterans seeking a creative outlet or to accomplish the more difficult task of re-acclimating to civilian life.

“That whole thing, when you get out [of the military] and you try to get into civilian society, it’s difficult,” she says. “Doing things like this, it’s an opportunity — to create a community that’s outside of the military but still with people who understand you. ... We are a special sorority-fraternity.

“To have that in a place of art, in a place of enjoyment,” she adds, “it’s so important.”

Bell worked in communications when she was in the Army. When she landed at the Shakespeare Center in 2012 she had studied film but hadn’t yet mapped out a professional path. Founder and Executive Artistic Director Ben Donenberg asked her if she’d be willing to run audio for a production of “As You Like It,” figuring it’d be a good fit.

It was. Bell is still involved in Center productions, including the upcoming “Macbeth.” She also now works in production at the Valley Performing Arts Center at

The Shakespeare Center’s program, which is focused on providing employment and job skills to vets, also covers tuition for some veteran workers to take technical theater courses at

Donenberg, who served on the National Council on the Arts for half a dozen years (a body that helps advise the NEA chairman on grant-making and programs), has long been focused on issues of veterans in the arts.

Cutting NEA support, he says, would mean “less jobs for veterans, especially chronically unemployed veterans. Plain and simple. It really curbs the ability to engage with the veteran community.”

Localized programs like the one at the Shakespeare Center aren’t the only veterans’ initiatives funded by the NEA. Through a program called Creative Forces: NEA Military Healing Arts Network, the agency helps fund art therapy at 11 clinical sites across the U.S. for veterans and special needs military patients — often those who have been diagnosed with traumatic brain injuries or psychological conditions.

Patients make art, write stories and create music as a way of dealing with trauma. The total budget for the program in fiscal year 2016 was $2.3 million. It is expected to grow to $2.6 million in fiscal year 2017.

“Supporting veterans in their home community or a successful transition after they have completed their assignment — especially for those who have been injured as a result of their service is not just the responsibility of the Department of Defense,” states NEA public affairs director Jessamyn Sarmiento via e-mail. “It is a duty shared by all of us.”

Lesley Currier, managing director at the Marin Shakespeare Company in San Rafael, in the Bay Area, concurs.

In 2016, her organization received a $10,000 NEA grant to conduct theater workshops for incarcerated veterans at San Quentin State Prison. In collaboration with the group Veterans Healing Veterans From the Inside Out, she led a group of more than a dozen inmate veterans who collectively wrote and staged a play titled “Freedom Isn’t Free.”

In many respects, she says, these artistic enterprises can serve as a way for veterans to come to terms with their experiences.

“One of the things that many of the men feel pretty strongly about is that there needs to be the same kind of training when you come out, that trains you how to be a civilian again,” she says, “that that could have helped them not get into trouble.

“There were men in the group who told stories in public that they had kept inside of them for decades,” she says. “Then they got the courage to share their stories in front of an audience. … They lifted a huge psychic weight off their shoulders.”

Other cultural programs are about giving veterans a voice. Around the country, community arts organizations, with funding from the NEA, lead playwriting workshops and memoir-writing classes that allow veterans to cultivate and share their stories in a society where they are a stark minority. (According to a 2014

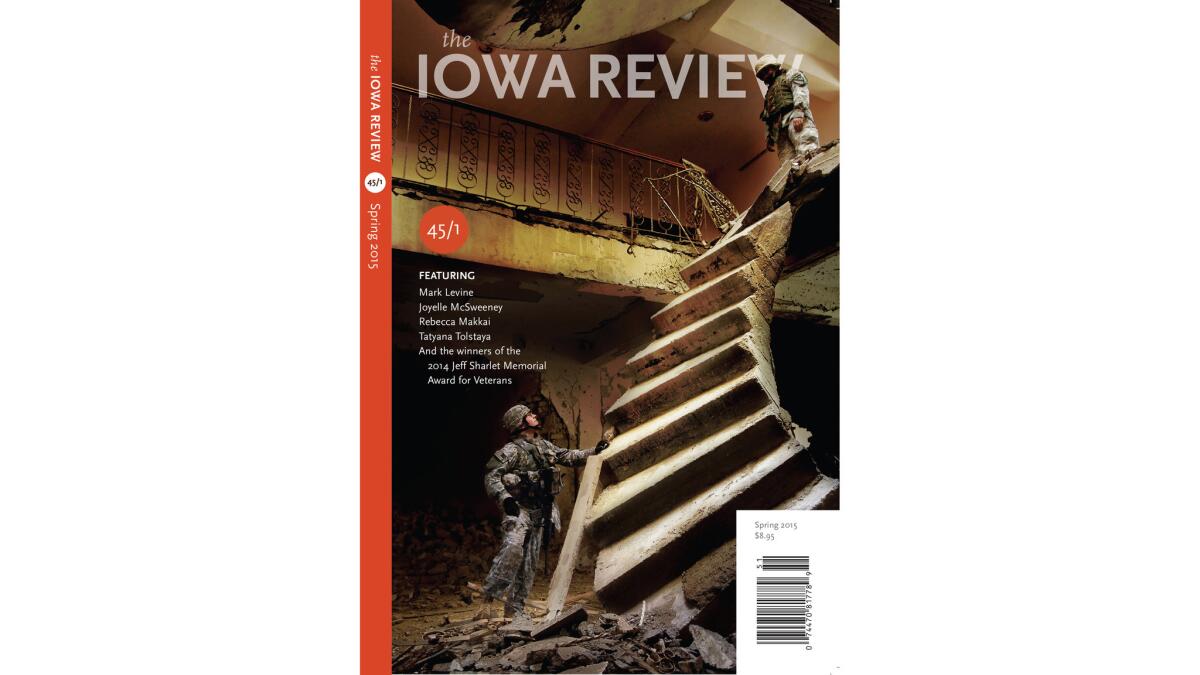

The Iowa Review, a literary magazine published three times a year by the

The initial award was funded by Sharlet’s family. (He was a writer and Vietnam vet.) But two grants from the NEA — a nearly $15,000 prize in 2014 and a $10,000 award in 2016 — helped the magazine expand the number of awards it gives.

“We were able to have runners-up, have them get a cash prize, have them get published,” says managing editor Lynne Nugent. “And we wanted to do it so that veterans didn’t have to pay submission fees.”

The grants have also helped cover small honorariums for the contest’s judges, which have included the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Robert Olen Butler (who served in the Army during Vietnam) and Anthony Swofford, a Gulf War veteran who is the author of “Jarhead.”

Hugh Martin, a poet who served in Iraq in the

Though the Iowa Review’s prize money is modest (first place is $1,000), the magazine provides an unparalleled platform. It is widely read in the world of letters, including by literary agents in search of new voices.

“We were extremely fortunate to have gotten the NEA grants that we got,” says Nugent. “We’ve leveraged them into more support from other funders. … It’s an endorsement of the quality of the program that it can lead to it becoming more institutionalized.”

Which raises an important point about the role the NEA plays at small cultural nonprofits. The grants can help organizations with razor-thin budgets innovate new programs and attract other donors.

“It begins a seed of something that grows and it makes more opportunity,” says Bryan Conger, interim artistic director at North Carolina’s Cape Fear Regional Theatre, where an NEA grant allowed the theater to create and stage “Downrange” and engage the local military community.

“And it lends credibility to a project,” adds his colleague Beth Desloges, the theater’s managing director. “If we hadn’t received the money from the NEA, we would have never received money from the Veterans & Theatre Institute,” which supports veterans in theater through a grant-making program.

We feel that having the NEA fund us, that’s a gold star or blue ribbon stamp of approval. It shows that what we do is high quality.

— Naomi Lichtenberg, Missoula Children's Theatre

The imprimatur that an NEA grant can bring can be essential to arts organizations.

“We feel that having the NEA fund us, that’s a gold star or blue ribbon stamp of approval,” says Naomi Lichtenberg, who does grant writing for the Missoula Children’s Theatre in Montana, which organizes theater programs for children on U.S. military bases around the world. “It shows that what we do is high quality. It makes a difference.

“That’s important to bear in mind,” she adds. “They have expert panels that evaluate the work that we do. The NEA is not just handing out money.”

The theater has received about half a dozen NEA grants since 2010 to support its work (which also includes helping kids stage theater productions in small, rural communities).

“We are, fortunately, not fully dependent on the NEA to keep our doors open,” says Teri Elander, the theater’s public relations director, but had nonetheless braced for cuts. “What’s important to us is what can happen over time,” says Elander. “The state art agencies, they receive money from the NEA, and the trickle-down could be significant over time.”

This is an issue of concern to every other organization contacted for this story.

“NEA funding trickles through organizations that we get funding from, like the state funding organization,” says Elise Butterfield, the programs director at Art Access in Utah. “So it’s not just the one-time funding thing. If they don’t get funding, we don’t get funding.”

George Sumner did two tours of duty as an Army helicopter pilot in Vietnam and recently took a playwriting workshop with award-winning dramatist Julie Jensen at Art Access.

In that workshop — which cost him a nominal $10 — he put together a one-act play titled “At the Wall” that tells the story of two veterans arguing over the purpose of the Vietnam War as they stand before the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. Last month it was performed by professional actors as part of a free staged reading at the Salt Lake Acting Company.

The experience of working with Jensen and producing the play was transformative, says Sumner.

“We had students in class who could not get through their script without weeping as they were reading it out loud,” he recalls. “There was some catharsis there.

“That’s a good thing to give someone,” he adds. “If it’s a veteran, it’s money well spent.”

Grants and the NEA

In fiscal year 2016, the National Endowment for the Arts made 2,500 awards (direct grants, partnerships and individual awards) that totaled $124 million. Here is how some of that money was spent:

- 25 grants totaling $499,000 for projects that support veterans and active military.

- 32 grants totaling $627,000 for projects that support individuals with disabilities.

- 15 grants totaling $202,000 for projects that support seniors.

FOR THE RECORD

May 8, 8:10 a.m.: An earlier version of this story reported that the Utah-based Art Access used its NEA grant to fund art-making and playwrighting classes. It employed the grant for art-making and memoir writing classes, as well as an exhibition of veterans’ art.

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

ALSO

What L.A. would look like without the NEA

How would the death of the NEA affect your community? California can cite 162 ways

The NEA works. Why does Trump want to destroy it?

If Trump thinks artists are a problem now, just wait: Why history tells us the fight ain't over

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.