Documentary ‘Abacus’ examines a reluctance to prosecute big banks, in favor of targeting the little guy

Steve James does not hold grudges.

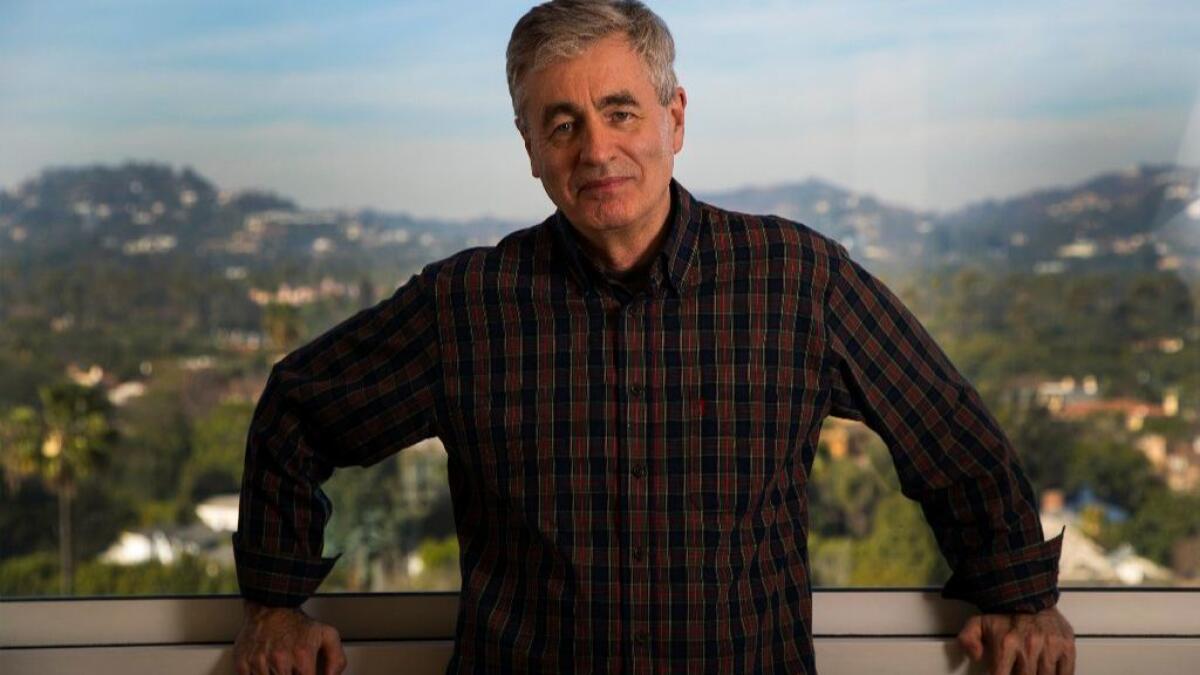

The fact that his wildly acclaimed 1994 film “Hoop Dreams” was not nominated for a documentary feature Oscar — one of the most controversial omissions in the history of the award — is in the past, as far as he’s concerned. The 63-year-old filmmaker is just happy that his latest work, “Abacus: Small Enough to Jail,” is getting Oscar recognition. The film, about a small bank in New York’s Chinatown that was the only financial institution to be criminally charged after the 2008 financial meltdown, is — finally — James’ first nomination in the documentary feature category.

“I don’t look at it as vindication” after the ‘Hoop Dreams’ snub, says James, speaking by phone from the Sundance Film Festival, where he was showing “America to Me,” a five-part series that deals with racial issues at an elite Chicago-area public high school, due out on Starz later this year.

WATCH: Video Q&A’s from this season’s hottest contenders »

“I was just thrilled” to get the nomination, says James, “because this story is so important and so timely, given who we have in the White House. The Sungs [owners of the Abacus bank] are an example of why this country was built by immigrants, and their story is also what’s wrong with this country in terms of the justice system. The fact this nomination could allow for a wider audience — I love that.”

James’ film follows the story of the Abacus Federal Savings Bank, the 2,651st largest bank in the country, which was hit with a 240-count indictment alleging grand larceny, fraud, conspiracy and other crimes. Abacus was founded and run by a tight-knit Chinese American family; the bank served an overwhelmingly immigrant constituency. The story of its legal troubles is a complex tale involving cultural misunderstanding, possible racism and prosecutorial over-reach. It’s a 21st century David vs. Goliath epic, asking why the Manhattan District Attorney’s office chose, out of all the banks in New York, to pick on this one.

“In many ways, it is a classic story in the way in which if you are not white, there is a different situation regarding justice in this country,” says James. “And the other thing that became clear to me making the film was that the D.A.’s office felt like they were on safe ground putting this bank on trial because the Chinese community in New York is politically disenfranchised. The D.A. didn’t have much fear as an elected official going after this bank.” As opposed to the giant Wall Street banks, like Goldman Sachs and J.P. Morgan Chase, that were connected to the financial collapse. After a four-month trial and a defense cost of $10 million, the bank and family were found not guilty on all counts.

“Abacus: Small Enough to Jail” is typical of James’ output. The veteran filmmaker likes to tell stories about people facing a turning point in their lives who in some ways are on the margins of society, but have a universal tale to tell.

“I tend to follow people facing a significant crossroads in their lives,” says James. “In ‘Stevie’ [2002], he was facing prison. In ‘The Interrupters’ [2011], you have people being part of the problem of violence in Chicago deciding they want to change it. Even in the Roger Ebert film [‘Life Itself,’ 2014] it ended up being a film about how he and his wife, Chaz, faced the last month of his life. And with the Sungs it’s about what could happen to them, and the bank’s future. I’m also interested in people who tend to be on the margins of society but whose lives say something about the world we live in. They are intimate stories, but I hope the viewer sees their lives in a larger context.”

James has not only been lucky with his choice of subjects; he came into the documentary field when it was morphing from staid, point and shoot filmmaking about limited subject matter into an exciting form encompassing a wide variety of stories and techniques.

“Within the documentary form is every conceivable genre that would apply to fiction films horror, thrillers, comedies, animated, everything, and that speaks to the explosion in the form,” he says. “I think the most innovative storytelling today is in documentaries.”

And, he adds, these days “there are more opportunities for your films to play, and more funding opportunities. When I first got in the business, I thought there were maybe three people in the world making a living at it. Now many more of us can make a living at it.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.