How Bernie Wrightson uncovered the soul of the monster in his work

- Share via

Ghouls, headless horsemen, werewolves and monsters in all stages of reanimation recently lost a key patron.

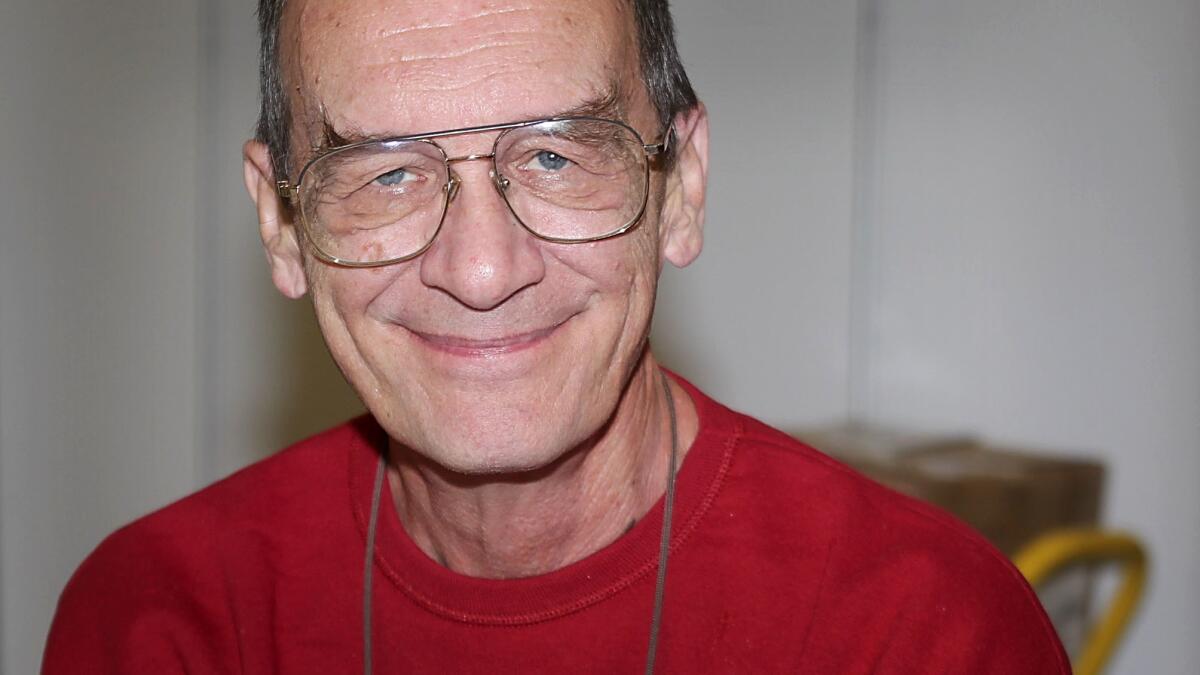

On March 19, Liz Wrightson confirmed that her husband, Bernie, beloved artist and creator of many things that go bump in the night, had died at 68 after a long battle with brain cancer.

As a statement on the artist’s website thanked fans and friends “for all the years of love and support,” comics and horror aficionados around the globe mourned the loss of their maestro.

“R.I.P. to the great Bernie Wrightson, a star by which other pencillers chart their course,” director Joss Whedon tweeted. “Bernie Wrightson was the first comics artist whose work I loved,” author Neil Gaiman wrote. Horror connoisseur

Though Wrightson may not have been a household name outside his canon, the passion of the testimonials was not surprising. No one uncovered the soul of a monster like Wrightson, who found the gorgeous in the grotesque. A few slashes of his pen revealed the twisted green lips and furrowed brow of Swamp Thing, a monster he created with writer Len Wein. The precise placement of each hair on the furry body of a werewolf rocketed the beast right off the page. Wrightson’s little lines were magic.

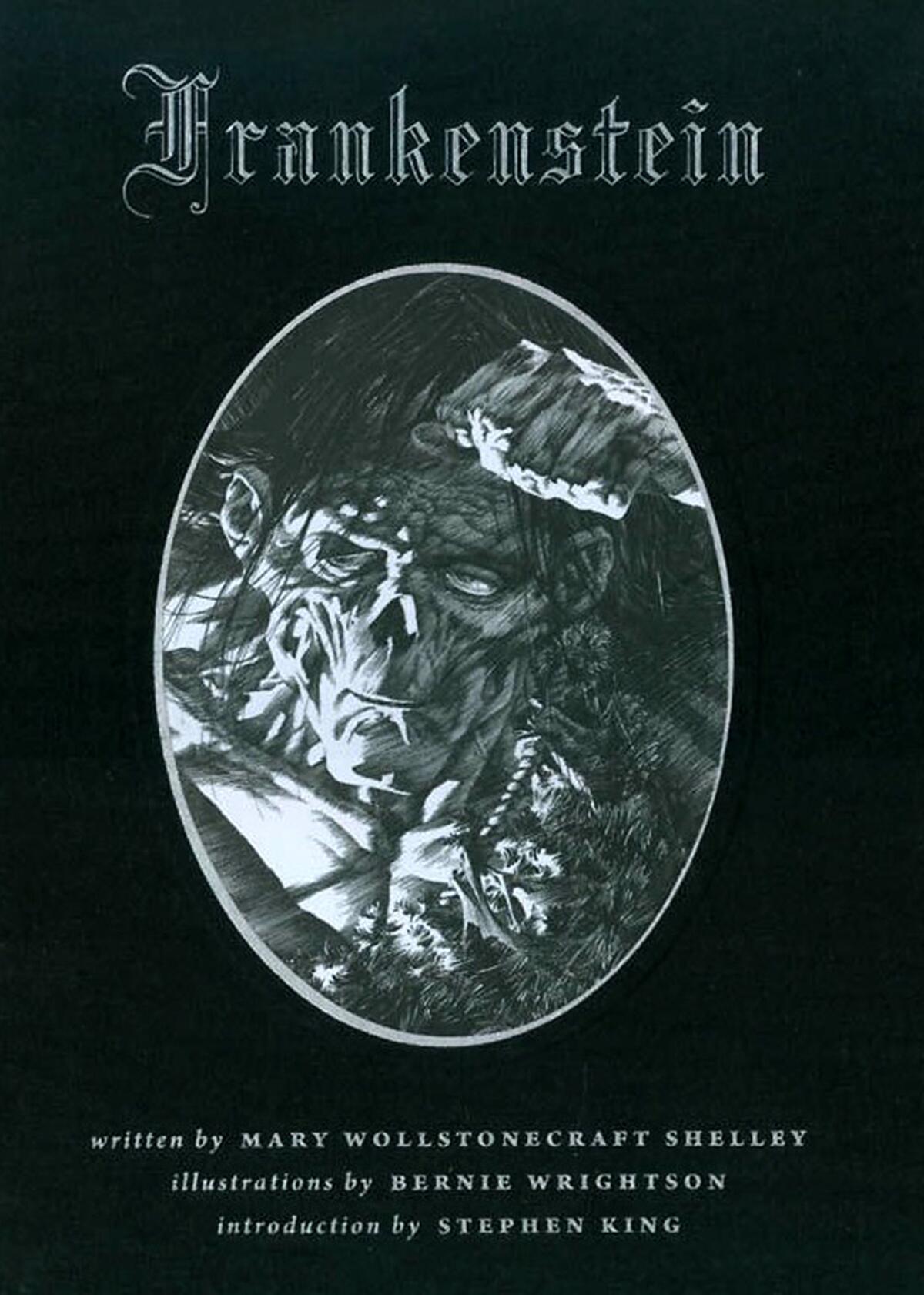

Best known for his transformation of Mary Shelley’s classic, the monster that became known by the name of his fictional creator. The 1983 book “Bernie Wrightson's Frankenstein” complemented Shelley’s tale with page after page of illustrations that forever changed the image of Frankenstein’s Monster.

Recasting the the lantern-jawed look made famous by actor Boris Karloff into a sunken-cheeked creature, Wrightson’s contoured lines made the undead beast look more like a lost, lonely soul. His strokes relined the face of a monster into the face of a corpse you couldn’t help but connect with.

The Maryland native began his career as an illustrator for the the Baltimore Sun, but after meeting genre artist Frank Frazetta at a comics convention he decided to follow his passion full time. Like many artists in the ’70s and ’80s, Wrightson headed to New York in hopes of landing a gig with DC, Marvel or any other comics publisher. At one point Wrightson was living in the same Queens apartment building as artists Allen Milgrom, Howard Chaykin and Walter Simonson.

“We'd get together at 3 a.m.,” Simonson recalled. “They'd come up and we'd have popcorn and sit around and talk about whatever a 26, 27 and 20-year-old guys talk about. Our art, TV, you name it. I pretty much knew at the time, ‘These are the good ole days.’”

Despite his own success as an artist for Marvel’s Thor, Simonson bowed to Wrightson. Even at an early age, he said, “we were all really in awe of his work, it was so good.”

Besides being able to draw anything he wanted, Simonson added, Wrightson was a master of value — the depth and tone of the colors.

“In drawing or in painting, one of the things that you control is the value, which is the light and dark,” he explained. “If you were to take your color TV set and somehow turn off the color and just have a black and white and gray picture, you're looking at the values of those color pictures. ‘Frankenstein’ is a complete masterpiece of value, using incredibly complex pictures, and yet you always see exactly what you are supposed to see. He drives the eye right where it needs.”

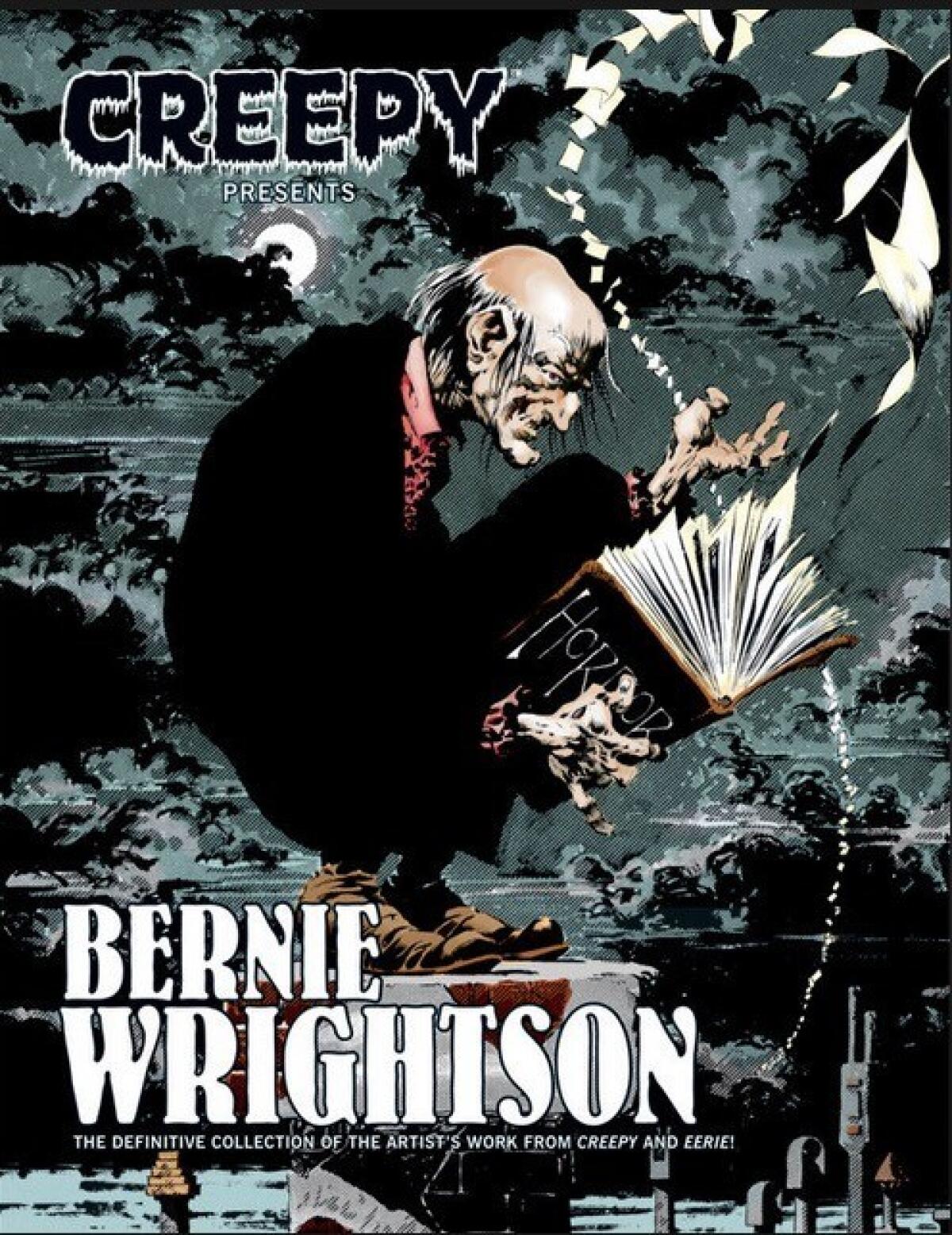

Moments after the news of Wrightson’s passing broke, the Internet was awash with Wrightson’s illustrations. Elaborate covers of Marvel’s “Doctor Strange” and issues of “Creepy” magazine and Swamp Thing tributes filled online feeds, but the most arresting (and shared) image came from his “Frankenstein” files. The black-and-white plates dominated the discussion. Artists and fans championed Wrightson’s use of negative space, his lifework and most of all his attention to detail.

His interpretation of Frankenstein’s laboratory, for example, “is a riot of detail,” said Scott McCloud, author of “Understanding Comics.” “It might take a moment before you even notice the corpse laying at the bottom of the composition on the left. That makes it a bit more of a treasure map. Bit more of a ‘Where Is Waldo?’”

“It's so complicated and yet he's able to show you what he wants you to see,” Simonson said. “In some ways [the lab scene is] the core of the story. It's where Frankenstein breaks the laws of God. I think people were just drawn to it cause it's so completely over the top and yet it's so completely controlled at the same time.”

Wrightson’s penciling work was equally unparalleled. Last year, during a tour of his extensive library of art and pop culture memorabilia at Bleak House, Del Toro instantly named Wrightson’s Frankenstein as the pieces in his catalog that were the hardest to find.

“They are very rare,” the director said at the time. “The people that have them don't let them go. It's taken me years to get that. I have nine out of the 13 favorite plates of the Frankenstein book that Bernie Wrightson ever did. The other four: one of them, no one knows where it is, and the other three are, I would say, very hard to pry away from the people that have them.”

But it wasn’t just the vision or the control or the intricate panels he drew like no other — that influenced so many — it was what lay behind them.

“He was a genius, and not just a monster guy,” “Hellboy” creator Mike Mignola said in heartfelt testimonial on Facebook. “Everything Bernie did had soul."

Twitter: @MdellW

ALSO:

'Westworld' stars confront the nature of the fembot

Negan promises he's 'just getting started,' but have 'Walking Dead' fans already seen enough misery?

For the love of monsters: An insider tour of Guillermo del Toro's Bleak House before his LACMA show

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.